PRODUCT

: A translator for all 3D models.

| TYPE | professional |

|---|---|

| YEAR | 2019 |

| FOR | gehry technologies |

| SITE | los angeles |

| TEAM | nathaniel wong |

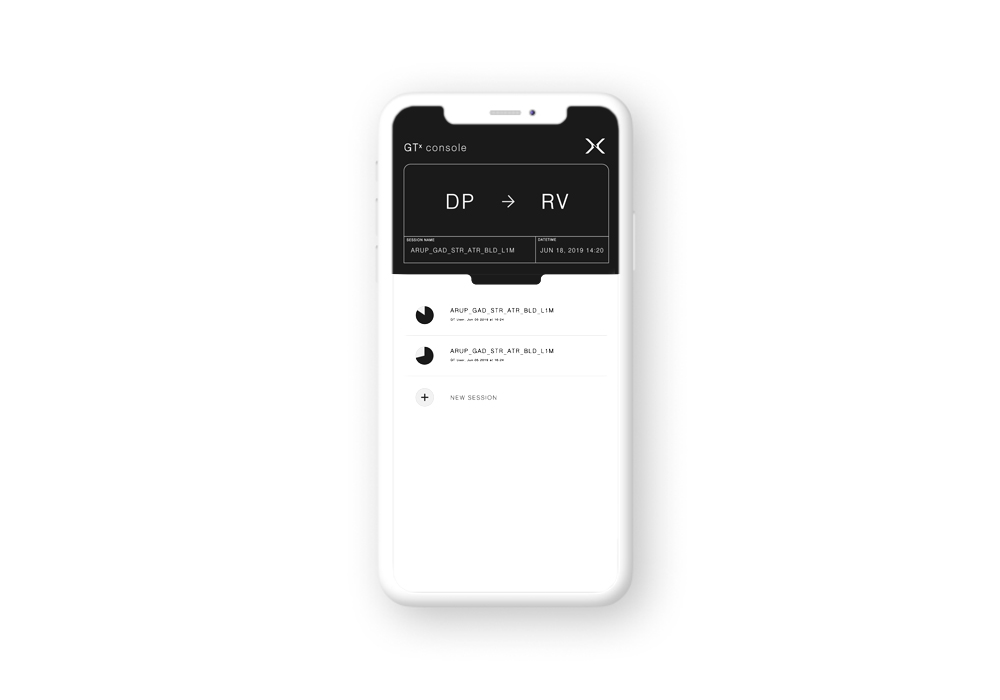

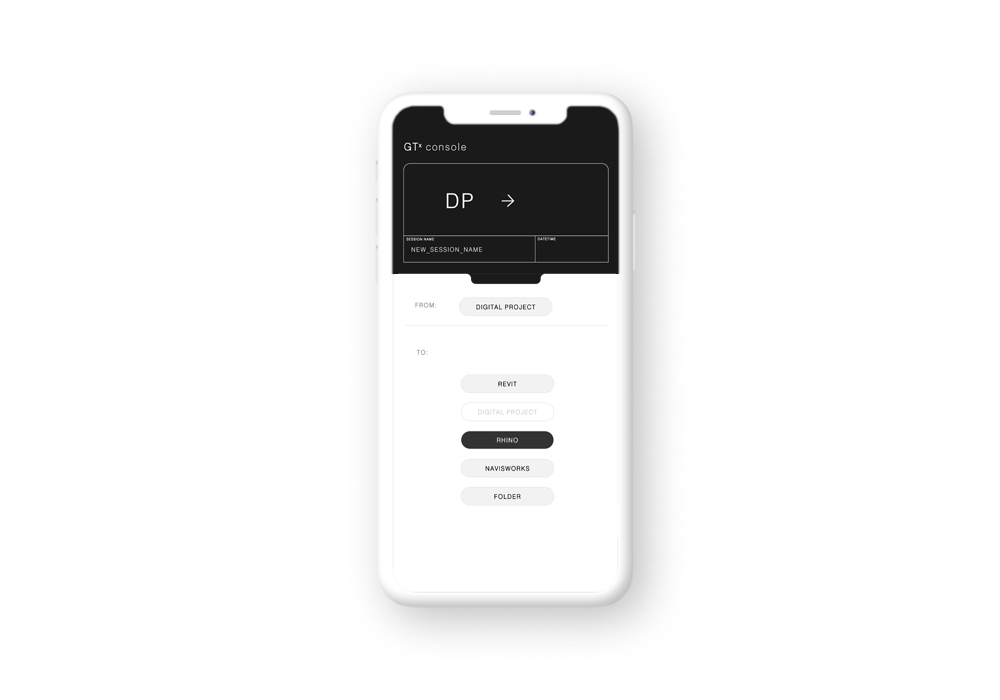

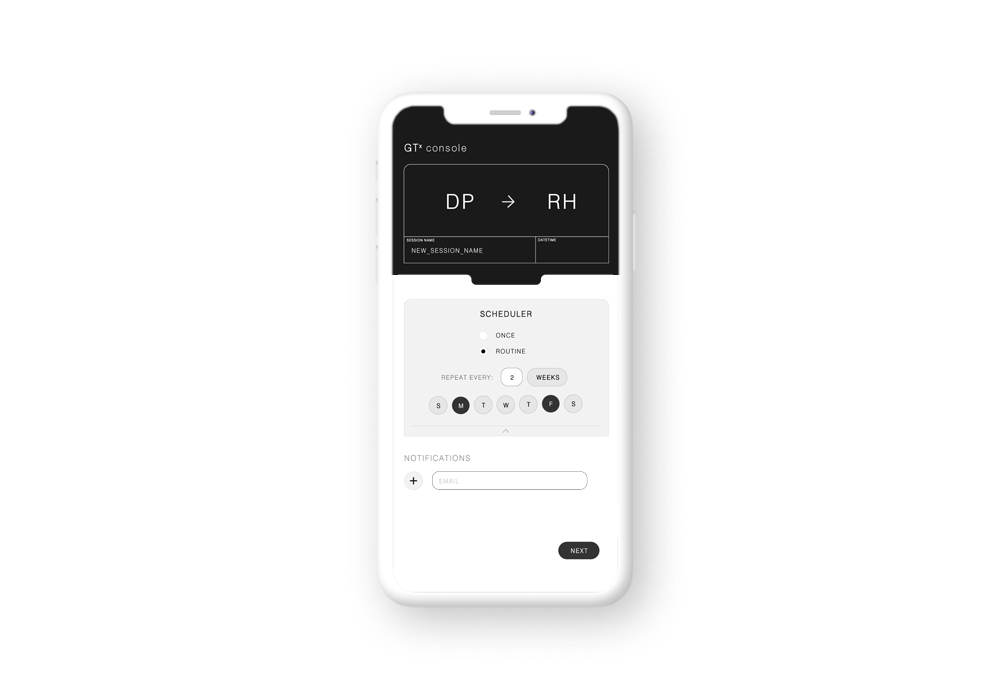

1.01CAD Library of Babel

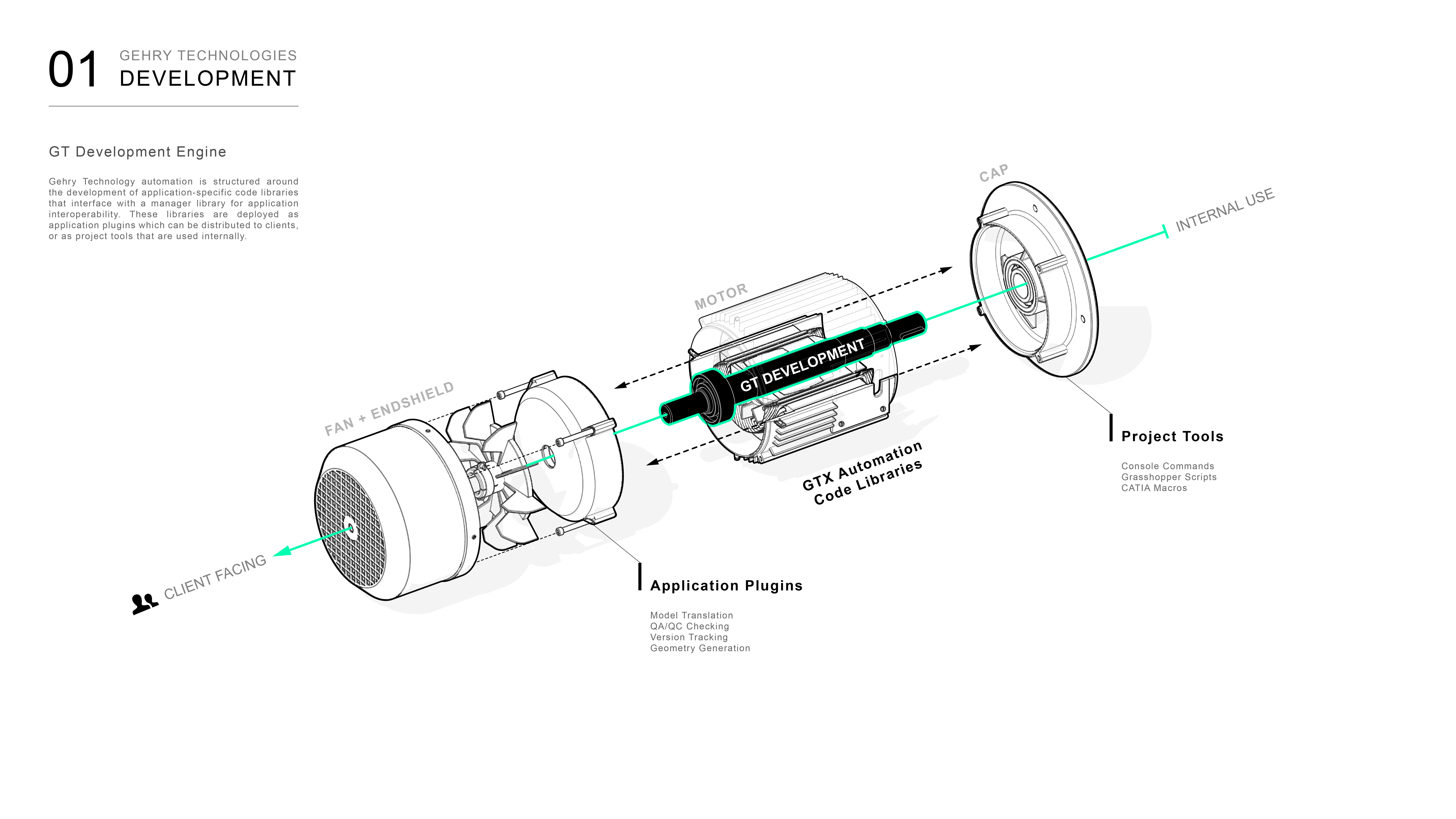

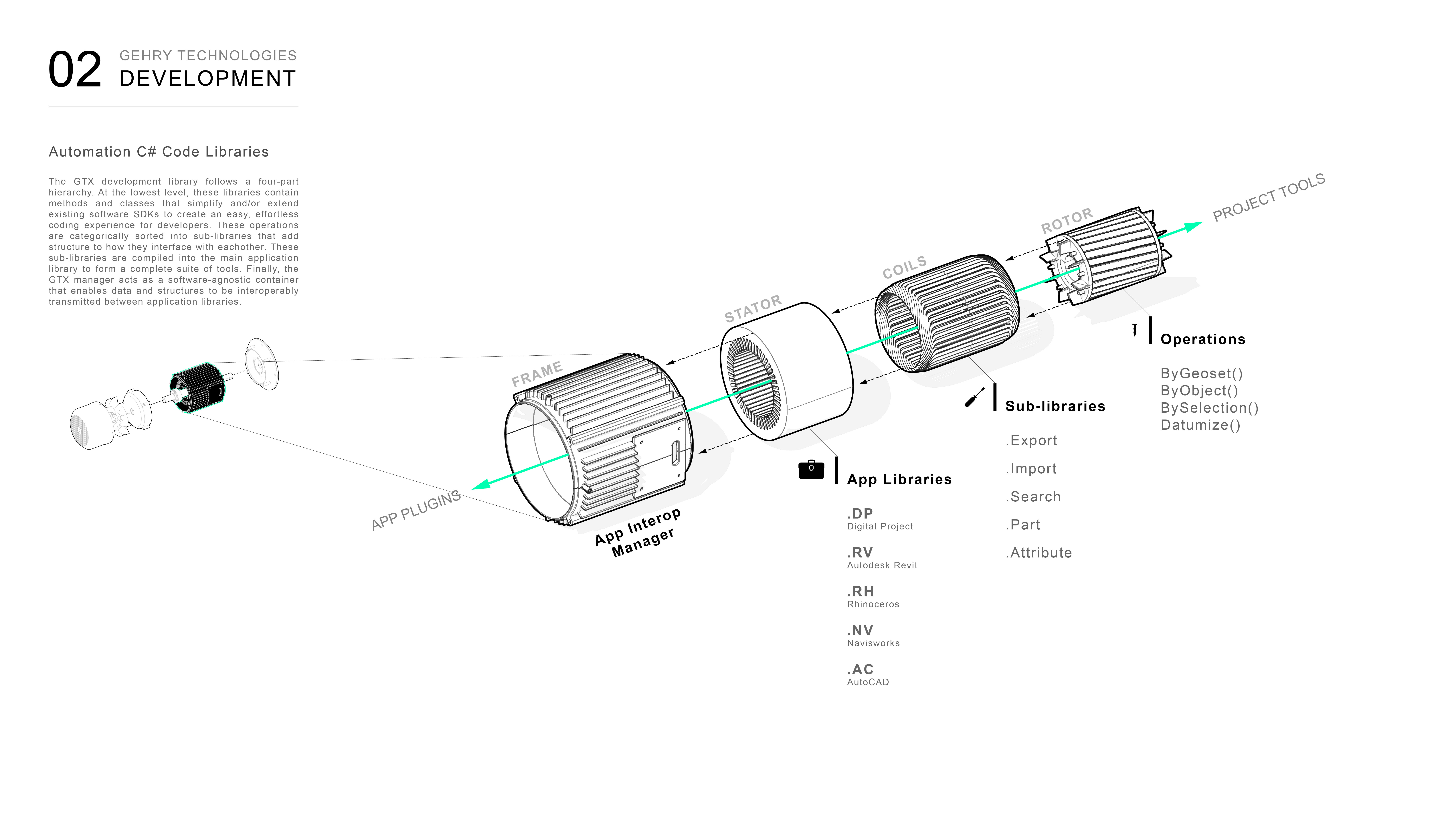

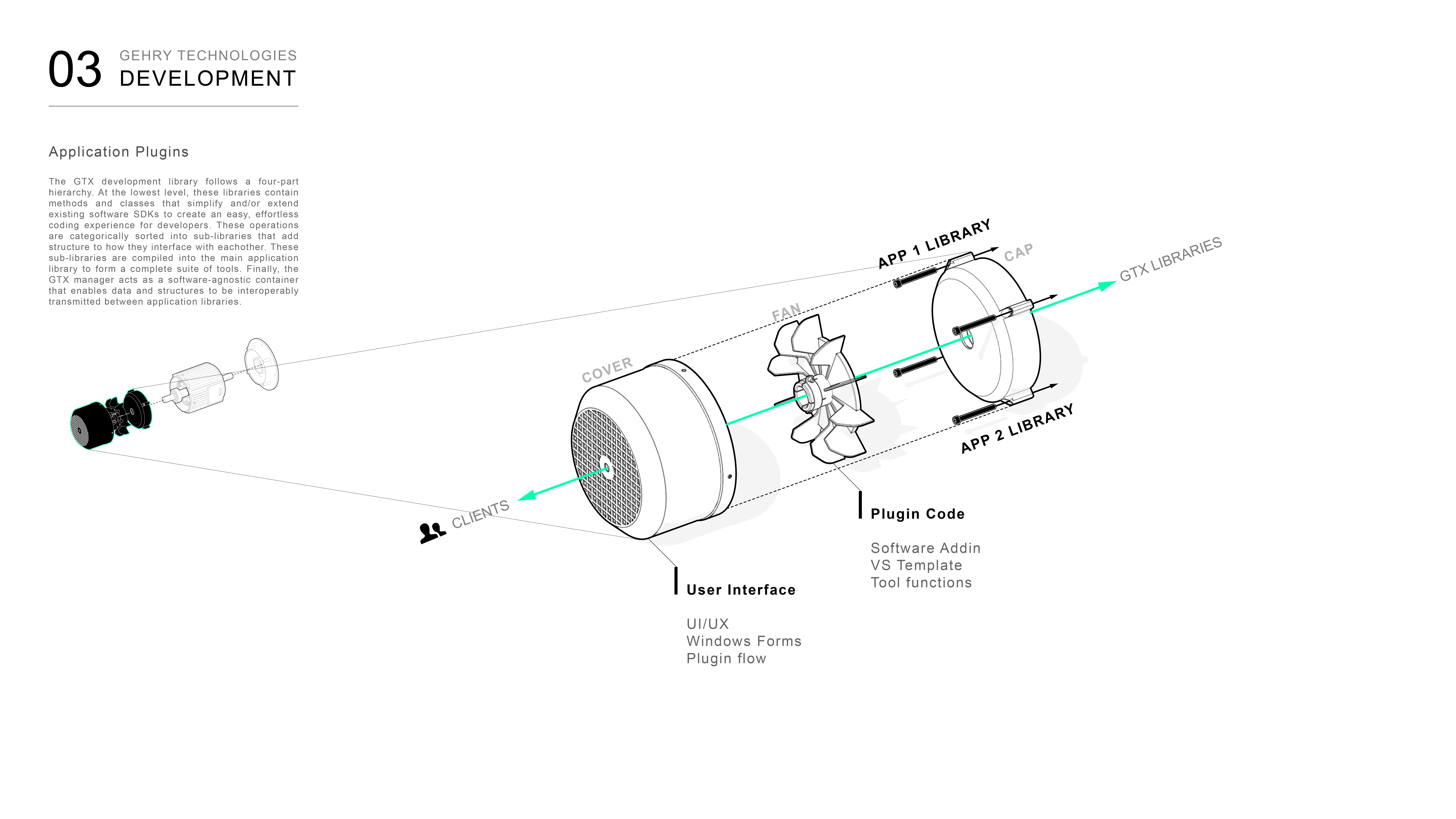

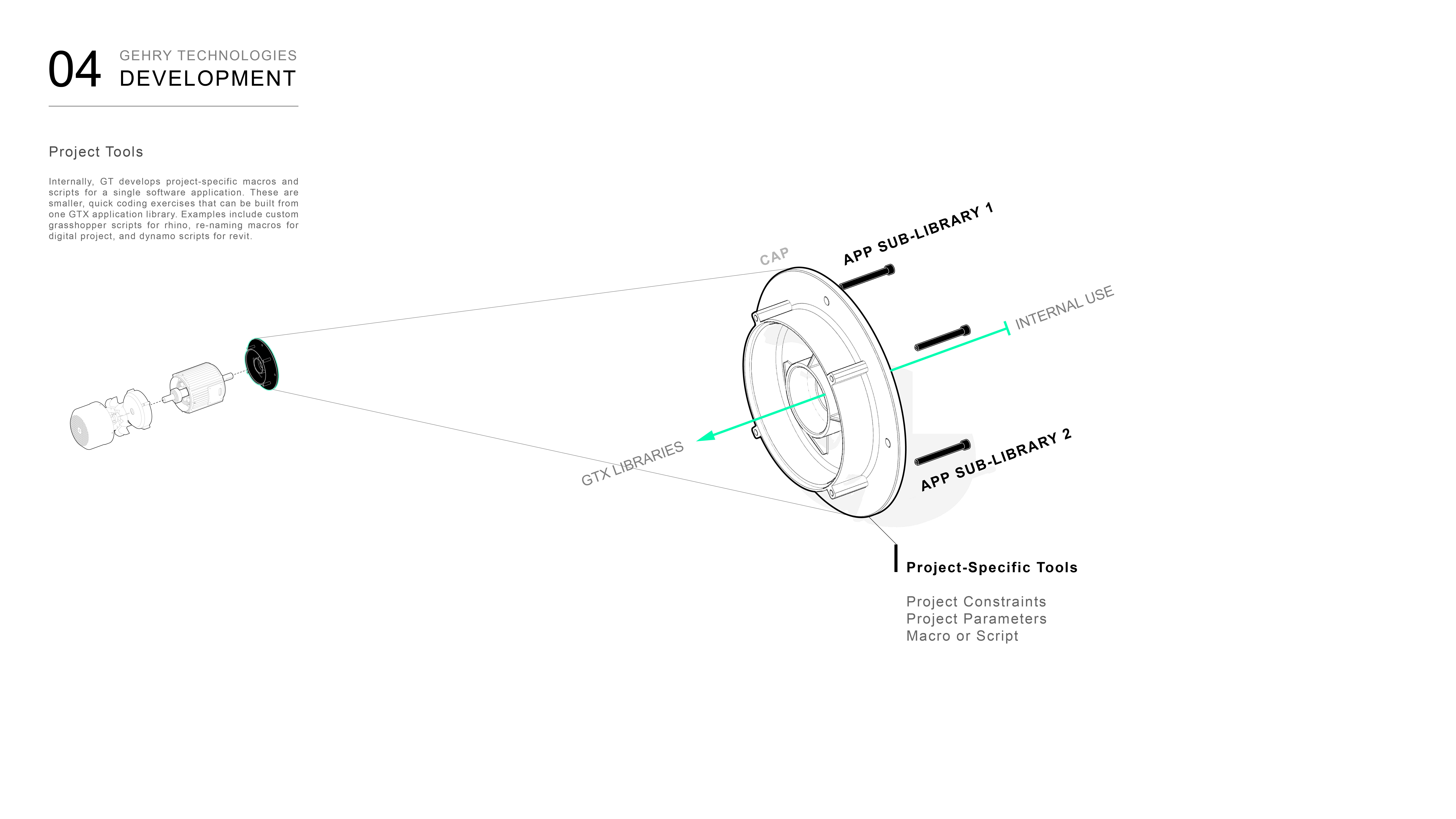

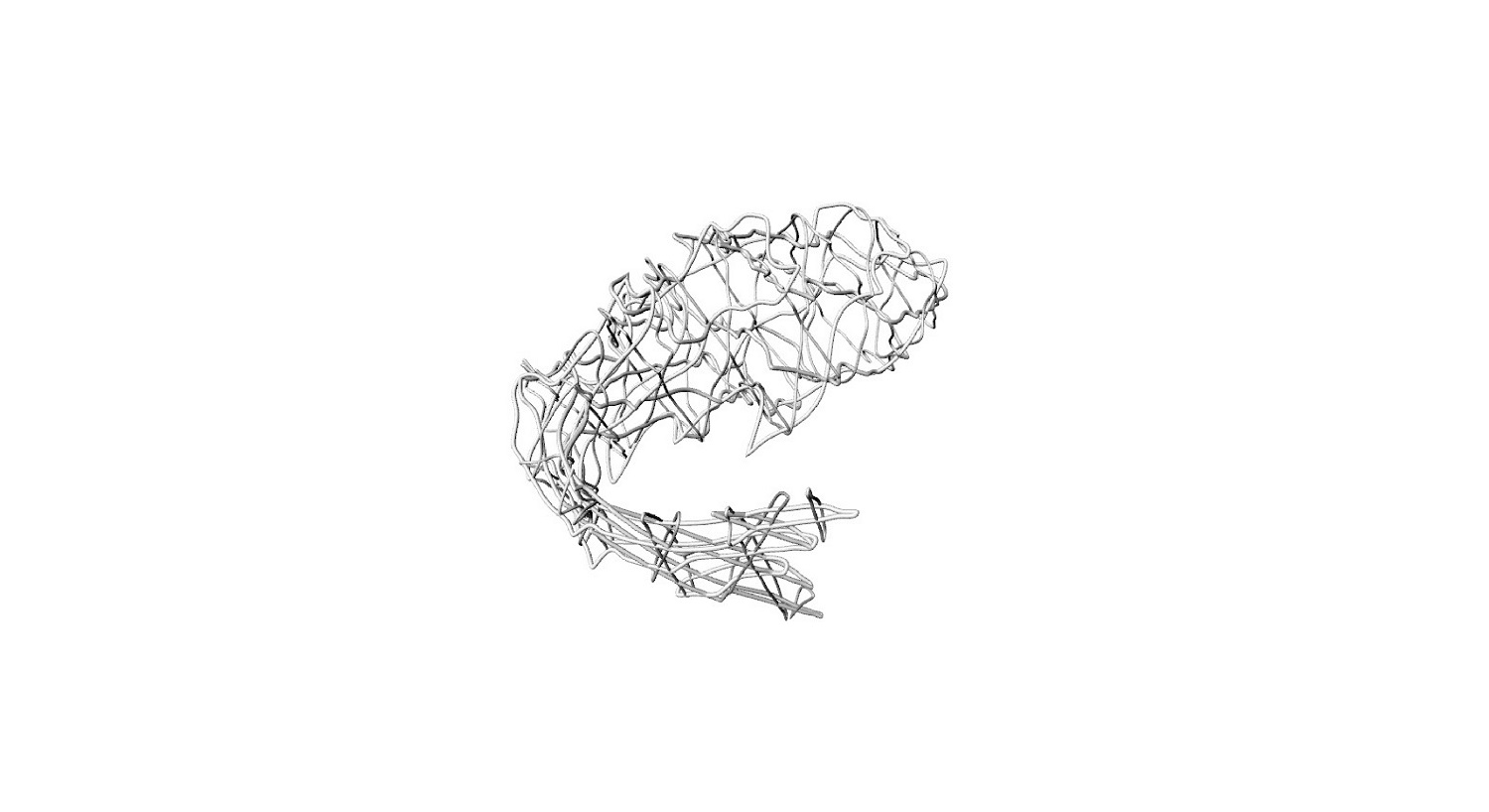

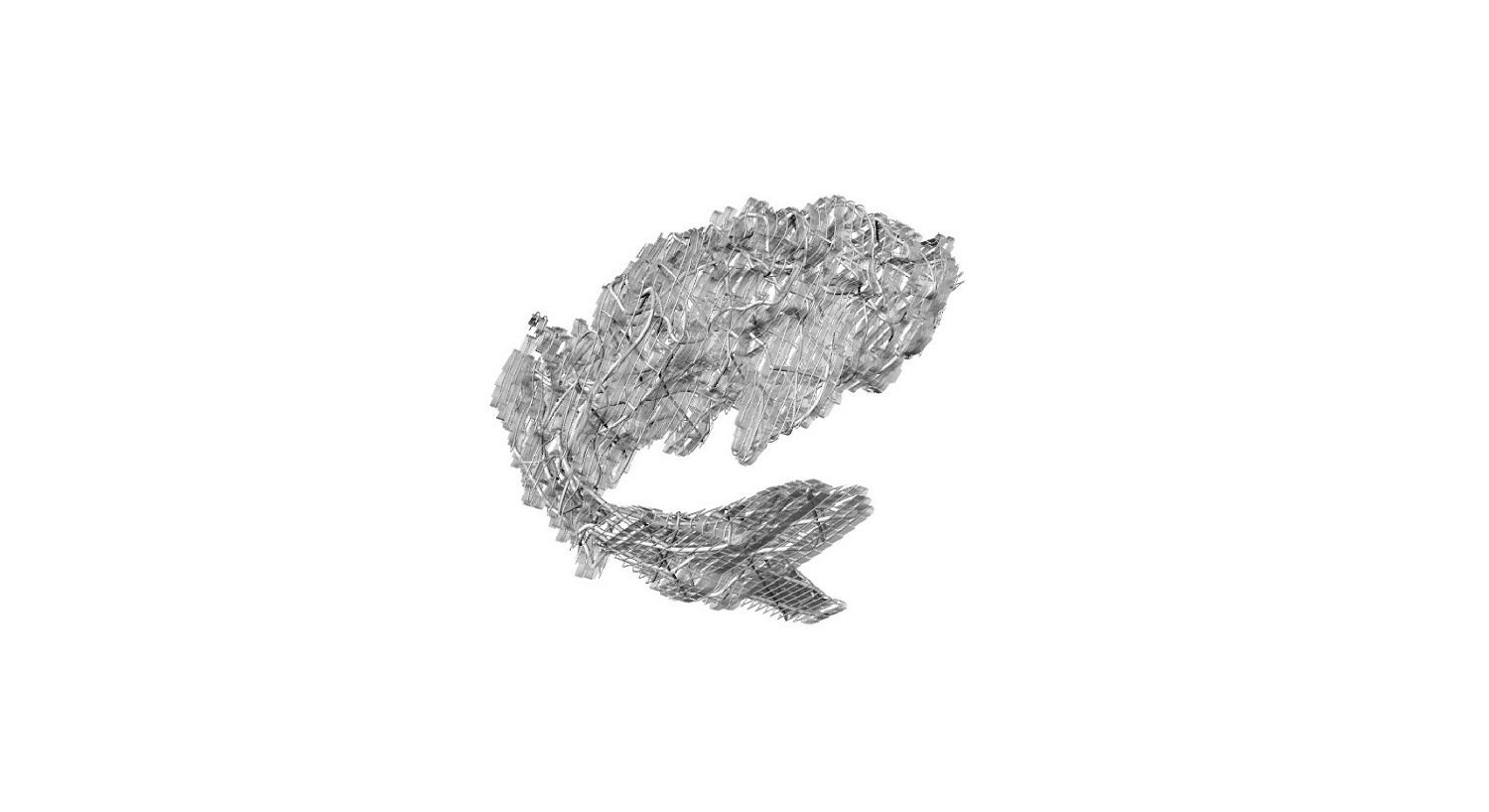

1.01The Gehry Technologies Dev Engine

COMPUTATION

: A 3D scan to structural fabrication script.

| TYPE | professional |

|---|---|

| YEAR | 2018 |

| FOR | gehry technologies / frank gehry architects |

| SITE | los angeles |

1.01Paper Tails

1.02 Paper => Steel + Glass

1.02 Takeaways

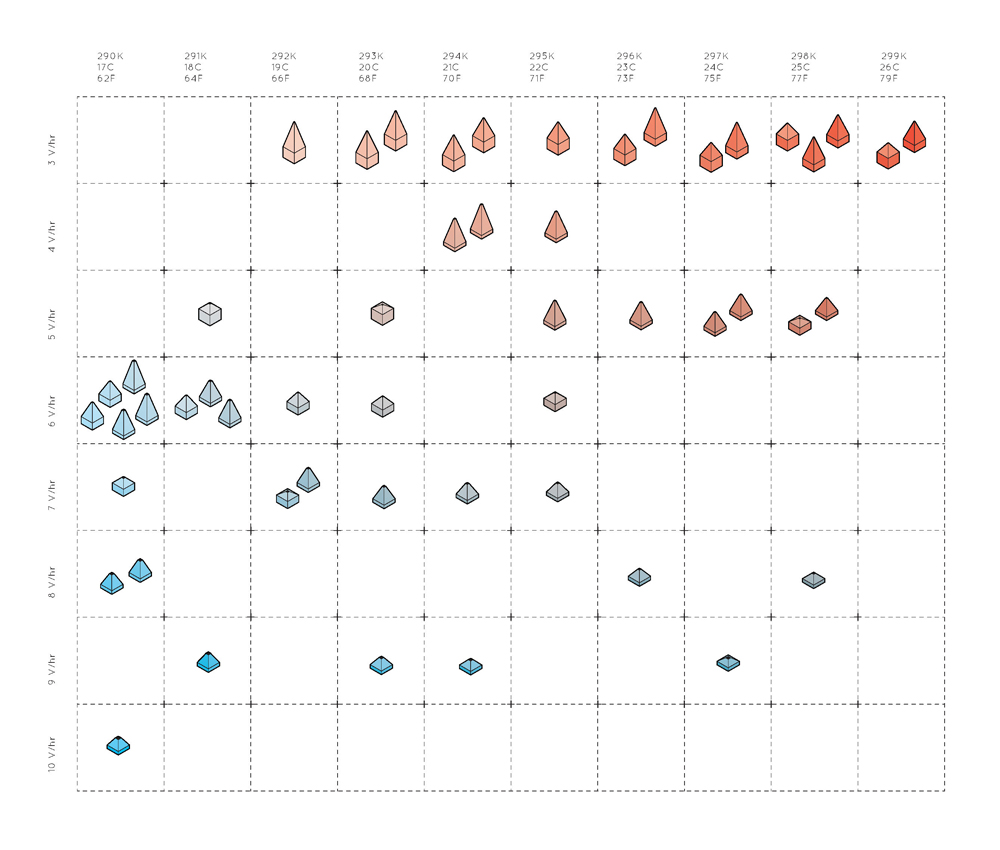

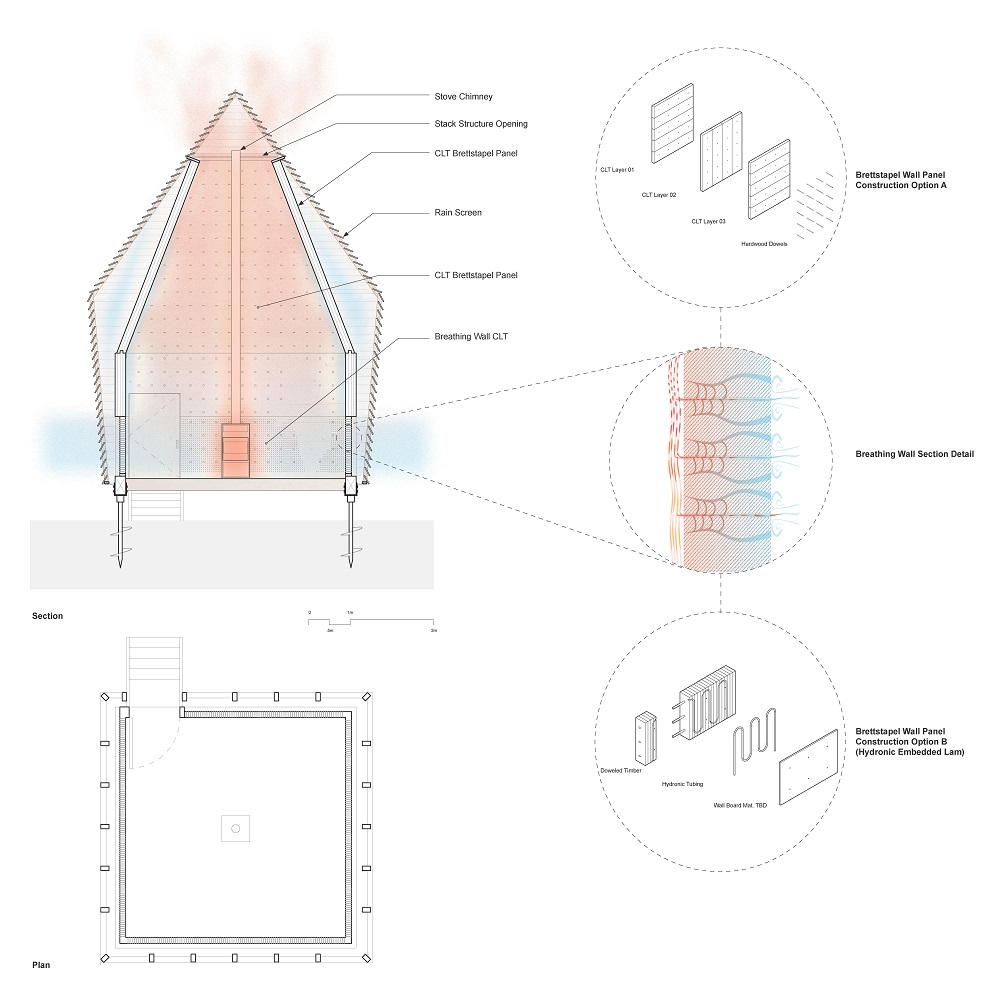

: Cabins for all climates.

| TYPE | elective |

|---|---|

| YEAR | 2016 |

| FOR | m.arch I |

| SITE | chile |

| TEAM | gavin ruedisueli, michael piscitello |

1

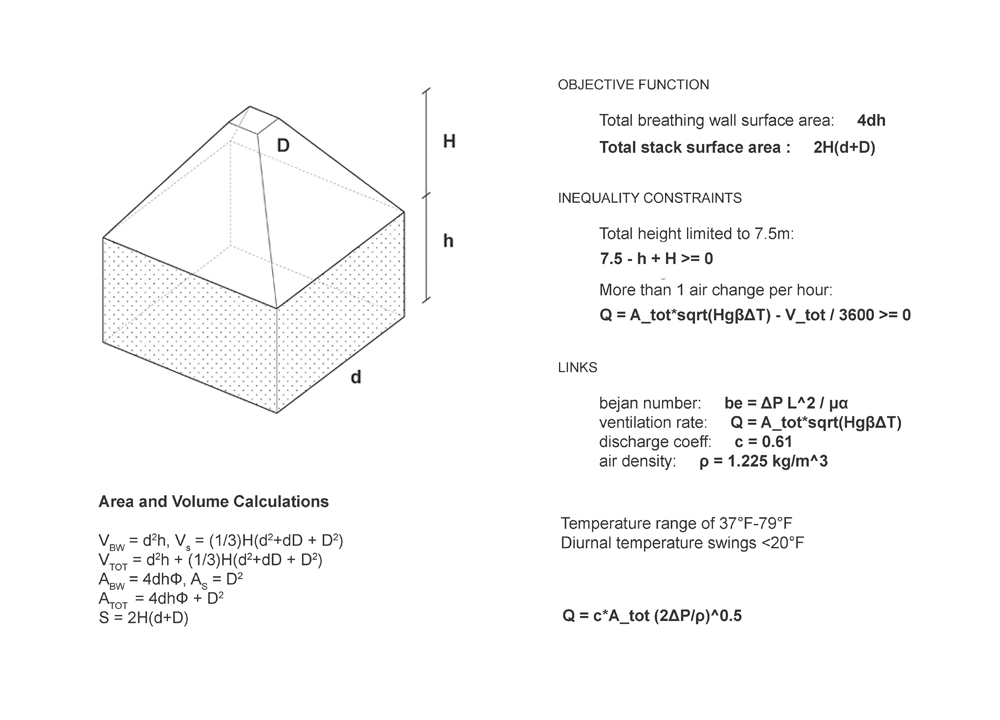

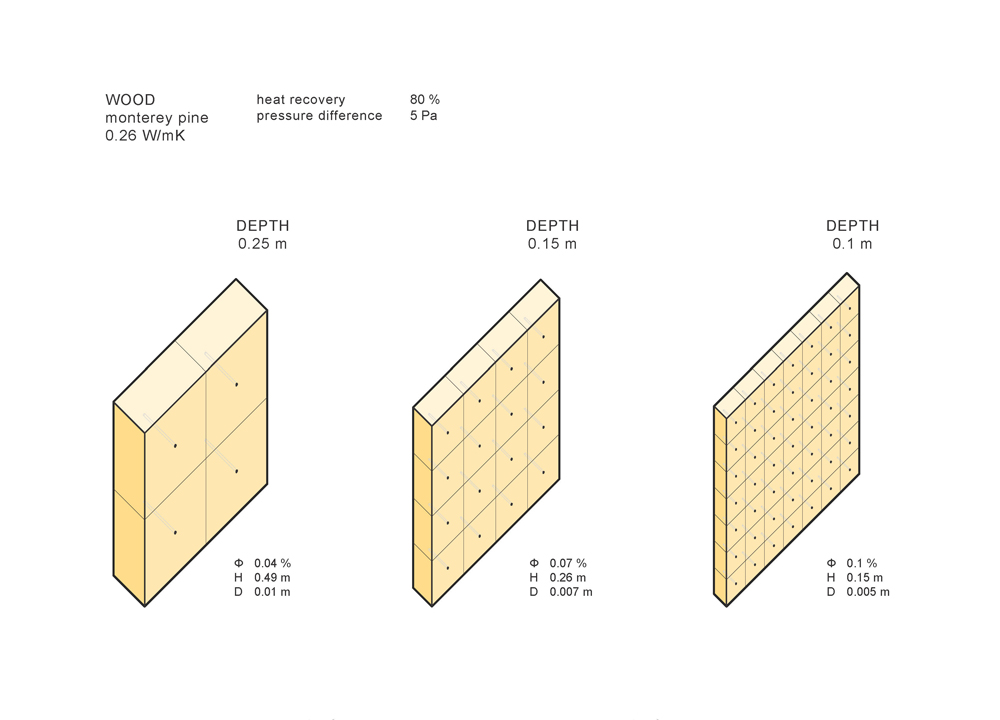

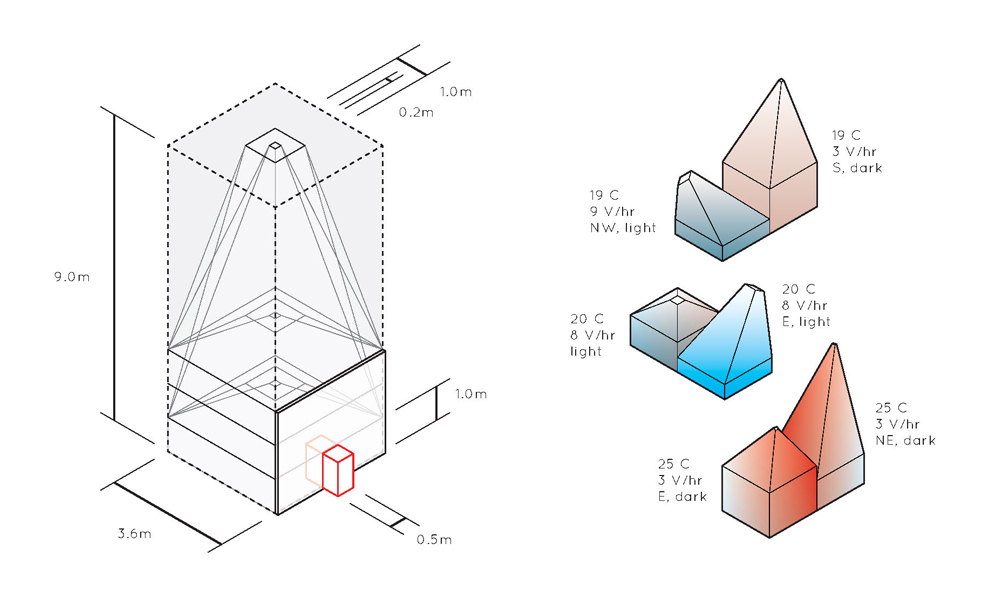

A MOST PASSIVE HUT

1.01An exercise in constrained optimization

2

DESIGNED FOR ALL CLIMES

1.01The space of all possible solutions

ARCHITECTURE

: A landfill in Lagos.

| TYPE | competition |

|---|---|

| YEAR | 2019 |

| FOR | arch out loud |

| SITE | lagos, nigeria |

| TEAM | zack matthews |

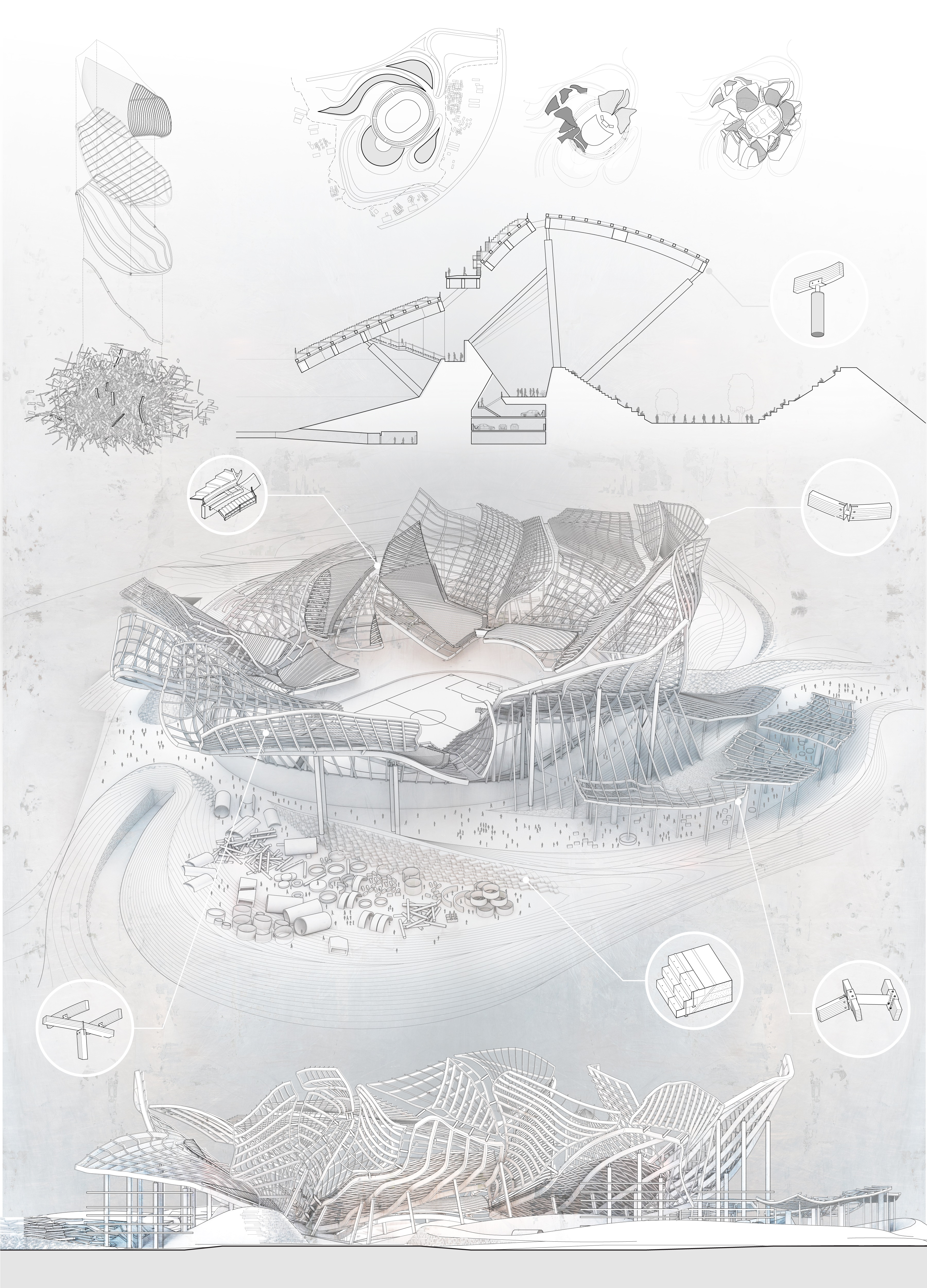

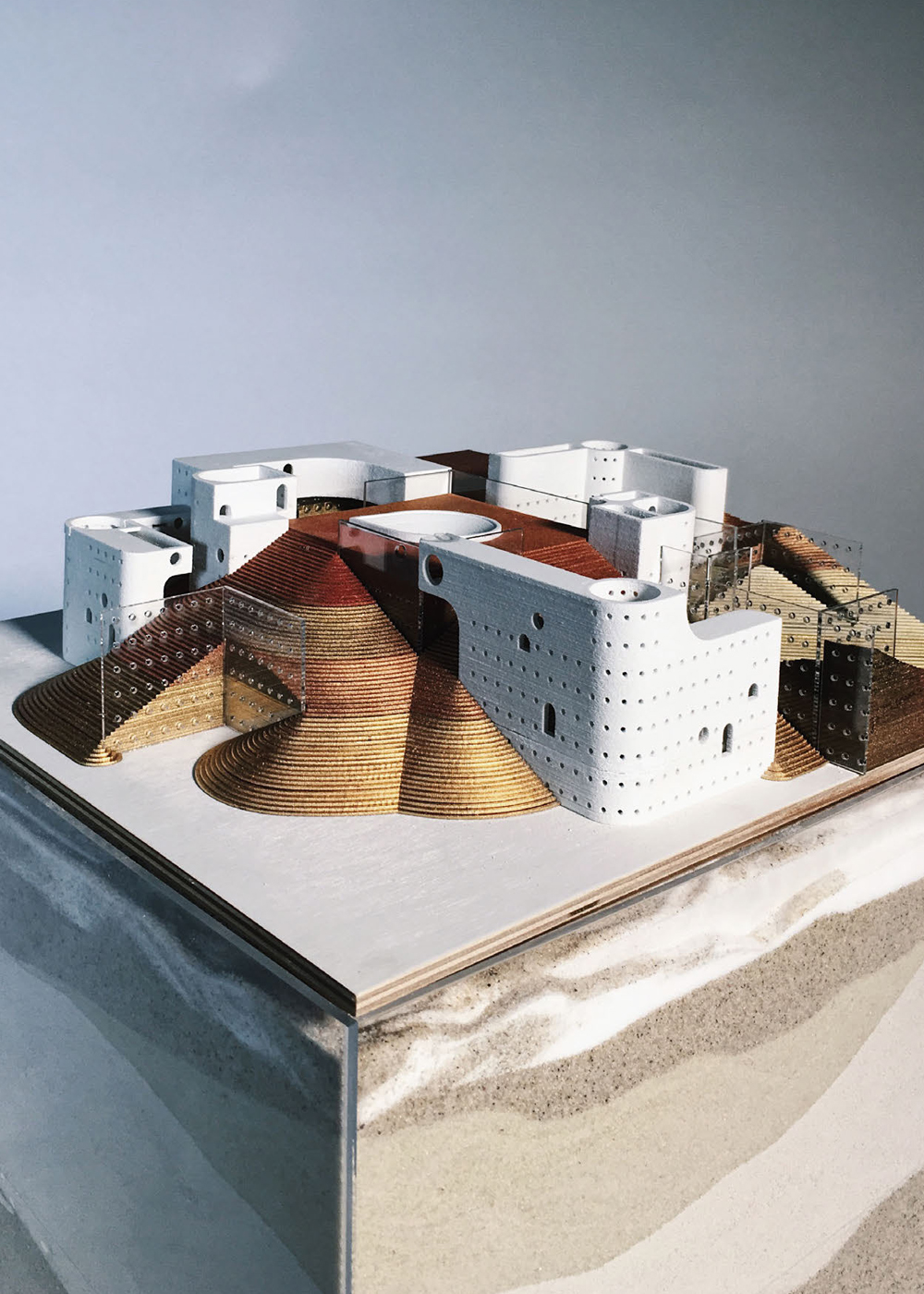

Stadium, Selvedged is an infrastructural proposal: a radical reduction of traditional stadiums into

framed canopies that double as grandstands, resting delicately upon an excavated field for the lightest

material footprint. Each petal is staged piecemeal, left raw, unfinished in perpetuity to adapt to the

changing programmatic needs of a rapidly urbanizing Lagos.

Stitched together from construction waste - lumber reworked into idiosyncratic glulam beams, concrete

rubble piled into landscape berms - the irregular shape and patchwork quality of Stadium, Selvedged

signifies the proposal as a byproduct of the city while exposing the bespoke craftsmanship of a

world-class stadium.

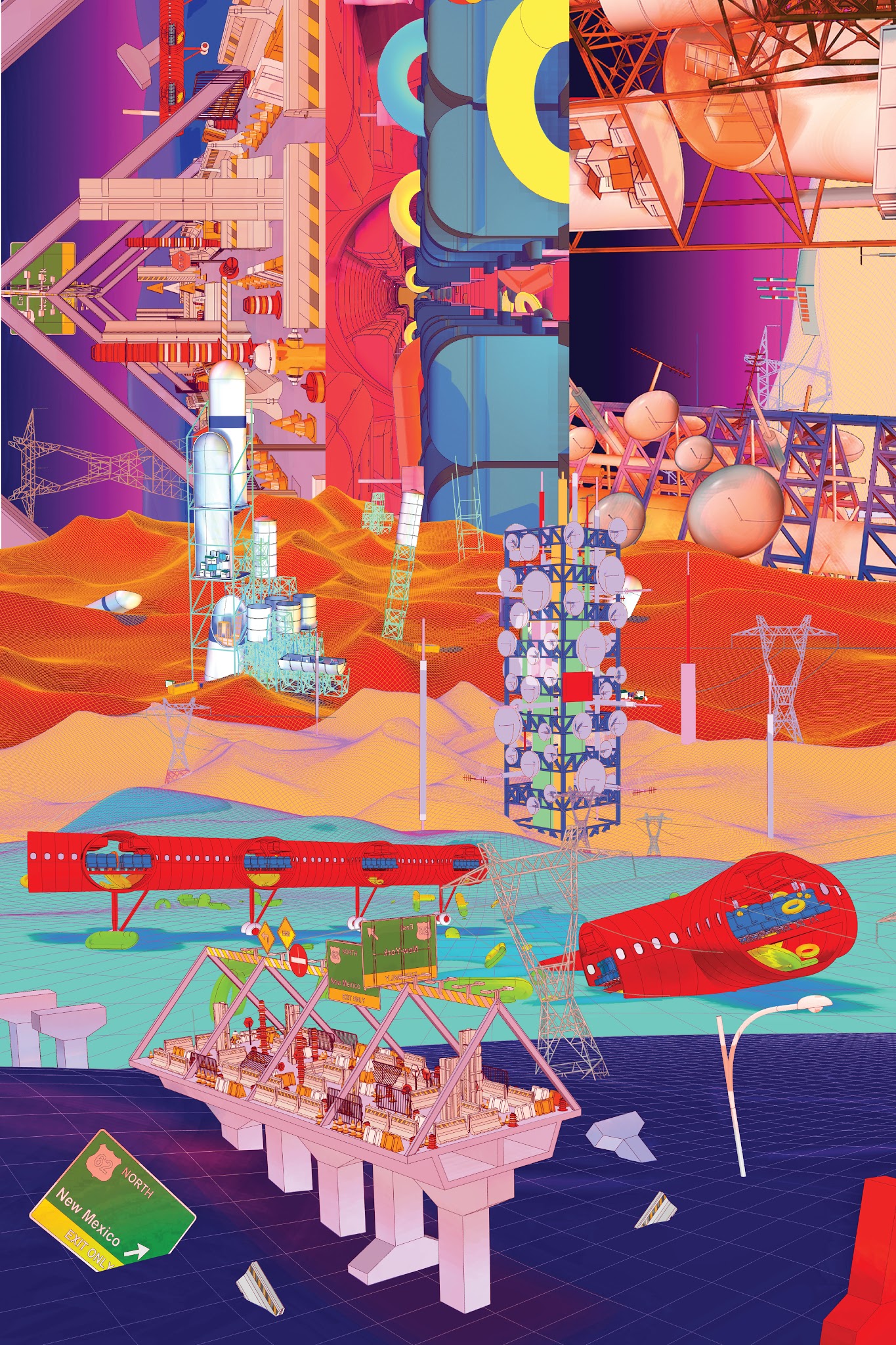

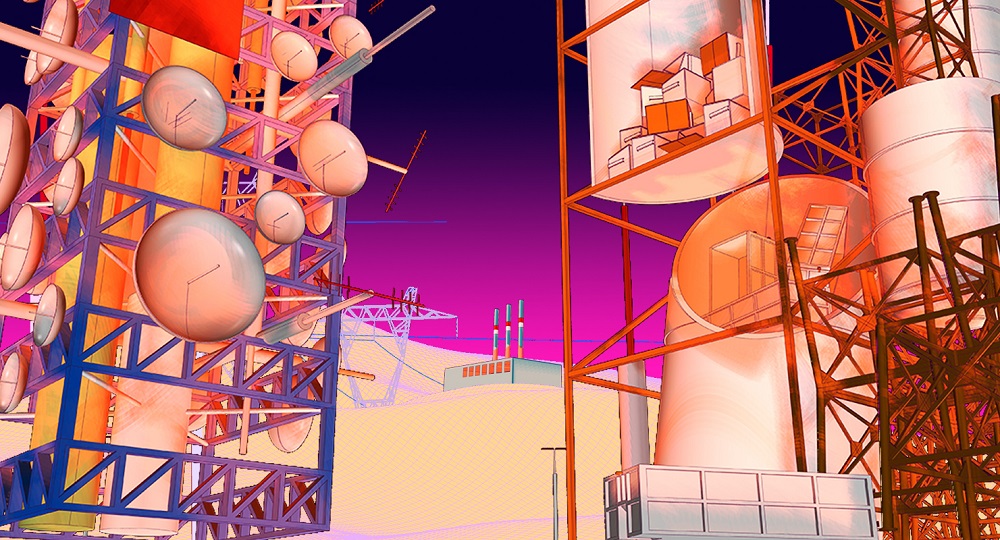

: Glimpses from the anthropocene, and other views.

| TYPE | competition |

|---|---|

| YEAR | 2018 |

| FOR | arch out loud |

| SITE | new mexico |

| TEAM | olivia heung |

"...With recognition of the protean nature of meaning-making; that the message of “waste”, “warning”, “storage”, and “communication” are all approached through a perambulating gestalt birthed through the loose affinities between objects both monumental and mundane. These objects and their assemblage, drawing gravitas from their multiplicity and material immunity from their functional obsolescence, are simultaneously the natural detritus of civilizations past and the nascent typologies of those yet to come. These follies! They are the quivering sextants by which we will navigate the ebbs and flows of the nuclear in our collective history..."

1

NUCLEAR WASTE: BRIEF

Since the Cold War, one of the most challenging and urgent tasks facing governments around the world

has been the disposal of transuranic nuclear waste. As a byproduct from nuclear weaponry production,

transuranic waste is not only harmful, but also boasts a formidable decay process lasting thousands

of years. To address this issue, millions of barrels of highly radioactive waste have been buried in

repositories deep beneath the earth's surface. One such disposal site is the Waste Isolation Pilot

Plant (WIPP) in New Mexico, United States. To ensure public safety, it is imperative that the site

remain undisturbed for the duration of the waste's decay process.

CHALLENGE: design a marker or marker system to deter inadvertent human intrusion into the Waste

Isolation Pilot Plant. The marker should exist as a means of passive institutional control of the site

for the duration of 10,000 years, following the closure and deactivation of the WIPP. The purpose of

the marker is to communicate with future generations that transuranic waste is buried within a

repository at the facility, located 2,150 feet beneath its surface, and should remain isolated until

the risks posed by its release have been sufficiently diminished.

2

PROPOSAL

"We don’t want to conquer space at all. We want to expand Earth endlessly.

We don’t want other worlds; we want a mirror."

- Dr. Snaut, Solaris

"A few hundred years hence, in this same place, another traveler, as despairing as myself, will mourn

the disappearance of what I might have seen, but failed to see."

- Levi Strauss, Tristes Tropiques

"Always new products - the other, invisible side of capitalism is waste. Tremendous amounts of waste.

We shouldn’t react to these heaps of waste by somehow trying to get rid of it; maybe the first thing

to do is to accept this waste, to accept that there are things out there which serve nothing. To break

out of this eternal cycle of functioning."

- Slavoj Zizek, Pervert’s Guide to Ideology

"The library will endure; it is the universe. As for us, everything has not been

written; we are not turning into phantoms."

- Jorge Luis Borges, The Library of Babel

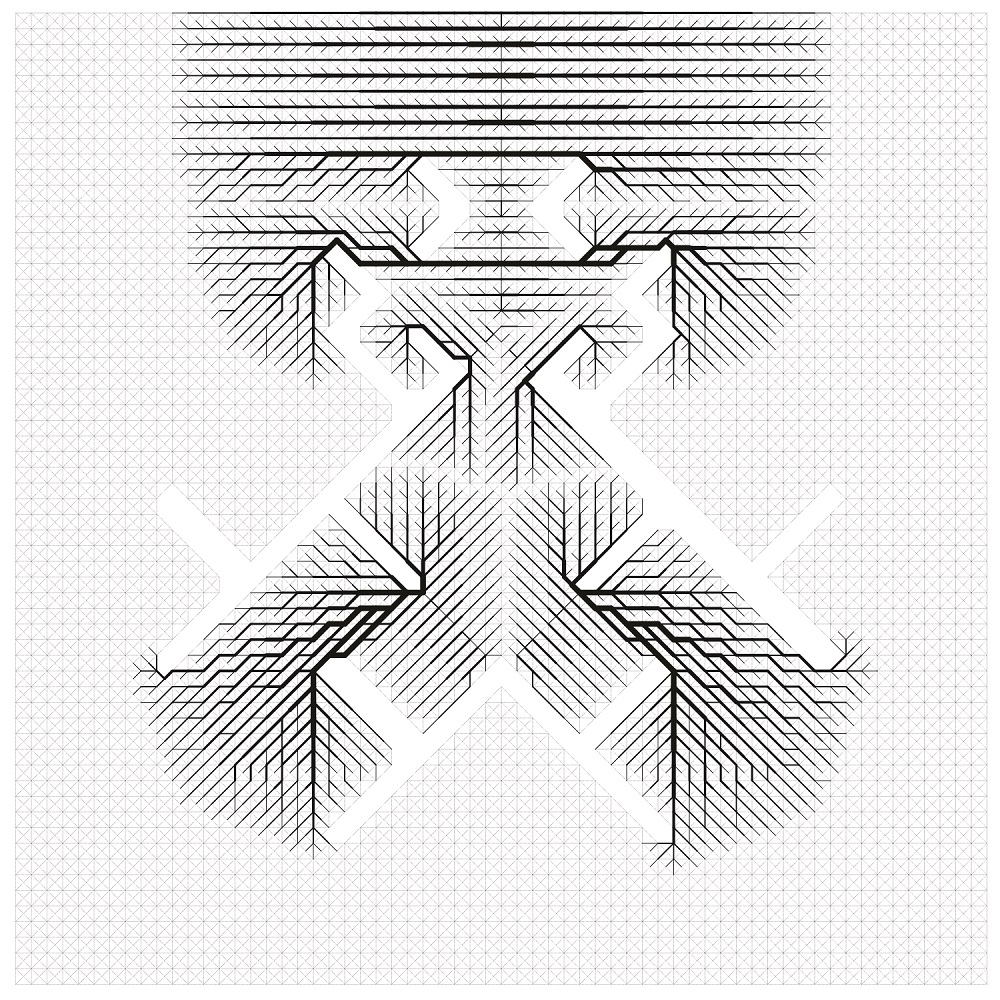

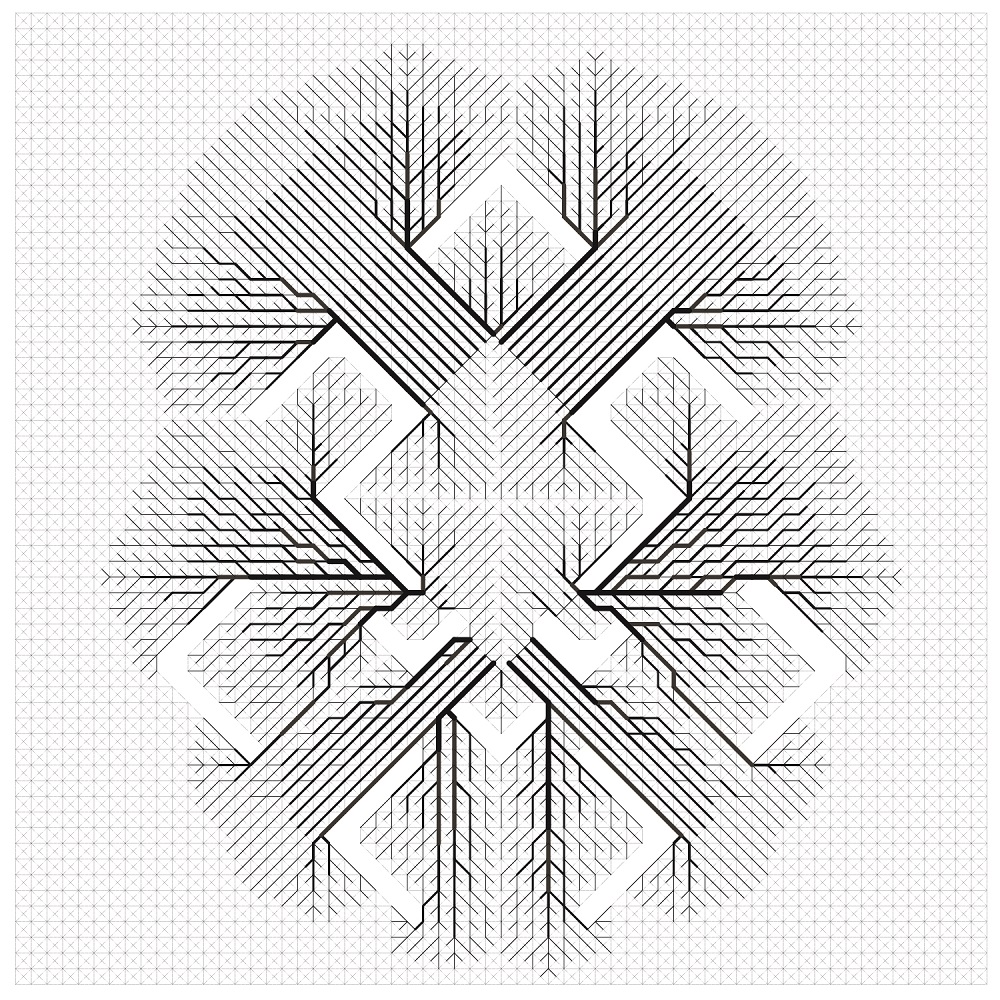

2.01Meaning-making and the Warning Object

Is it possible to anticipate the semiotics of "warning" over the course of ten millenia of sentient life? Rather than to attempt to design a single form which carries with it this element of danger and caution, we operate with the understanding that the objects of meaning-making have always been and will always continue to fluctuate in how they convey signifiers, in their means of production and manufacture, and in their varying degrees of usefulness/uselessness. It is not any one object or shape that functions as marker universal; it is the traffic cone, barbed wire, ammunition, caution tape, oxygen mask, highway divider, and stop sign that collectively approach the contemporary message of "pay attention, stay away".

2.02A Language of Wasteful Assembly

Just as words are the building blocks of a syntactical structure wherein language acquires meaning and intent, these markers of waste also need intentional assembly in order to communicate their nonverbal message of warning. The act of assembly is a powerful indicator of sentience - it can turn an otherwise incidental pile of objects, placed by forces of nature or some other cocktail of uncoordinated events, into an indication that something intelligent had once passed through and taken action. Like cairns on a trail, the assembly of these warning objects - with no discernible contextual use on their own - now activates the empty swathes of New Mexican desert with speculations of previous occupation, significance, and intent.

2.0310,000 year archive

As the language of assembly and the objects of warning change over time to reflect the current methods and materials of industrial production and consumption, the accumulation and perpetual metamorphosis of these patchwork structures also functions as a sort of dynamic archive: at every moment a freezeframe of the methodologies and object associations that convey the meaning of waste, of danger, of the nuclear. The processing of nuclear waste is elevated to the status of archive maintenance, where individually each warning object has little value within their contemporaneous context of production (who would traverse the desert to steal a traffic cone?), but collectively through assemblage they acquire semiotic significance through their relationship to eachother, and the massive, spatialized scenes they present to the wayward traveler, up close and from afar.

: Tiles, on a Roof, in Los Angeles.

| TYPE | built |

|---|---|

| YEAR | 2018 |

| FOR | dopium LA |

| SITE | los angeles |

| TEAM | benzi rodman, anna herman |

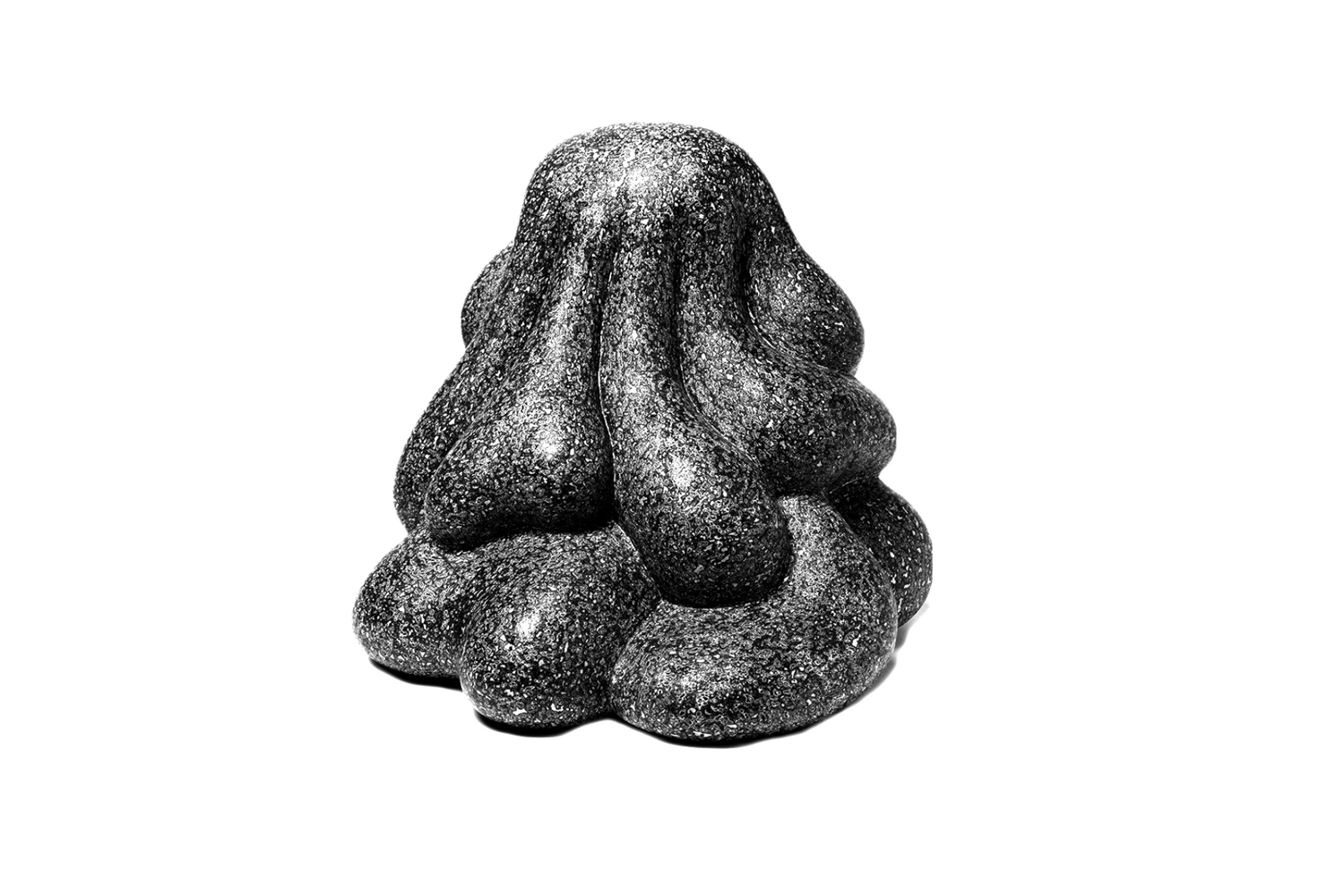

1

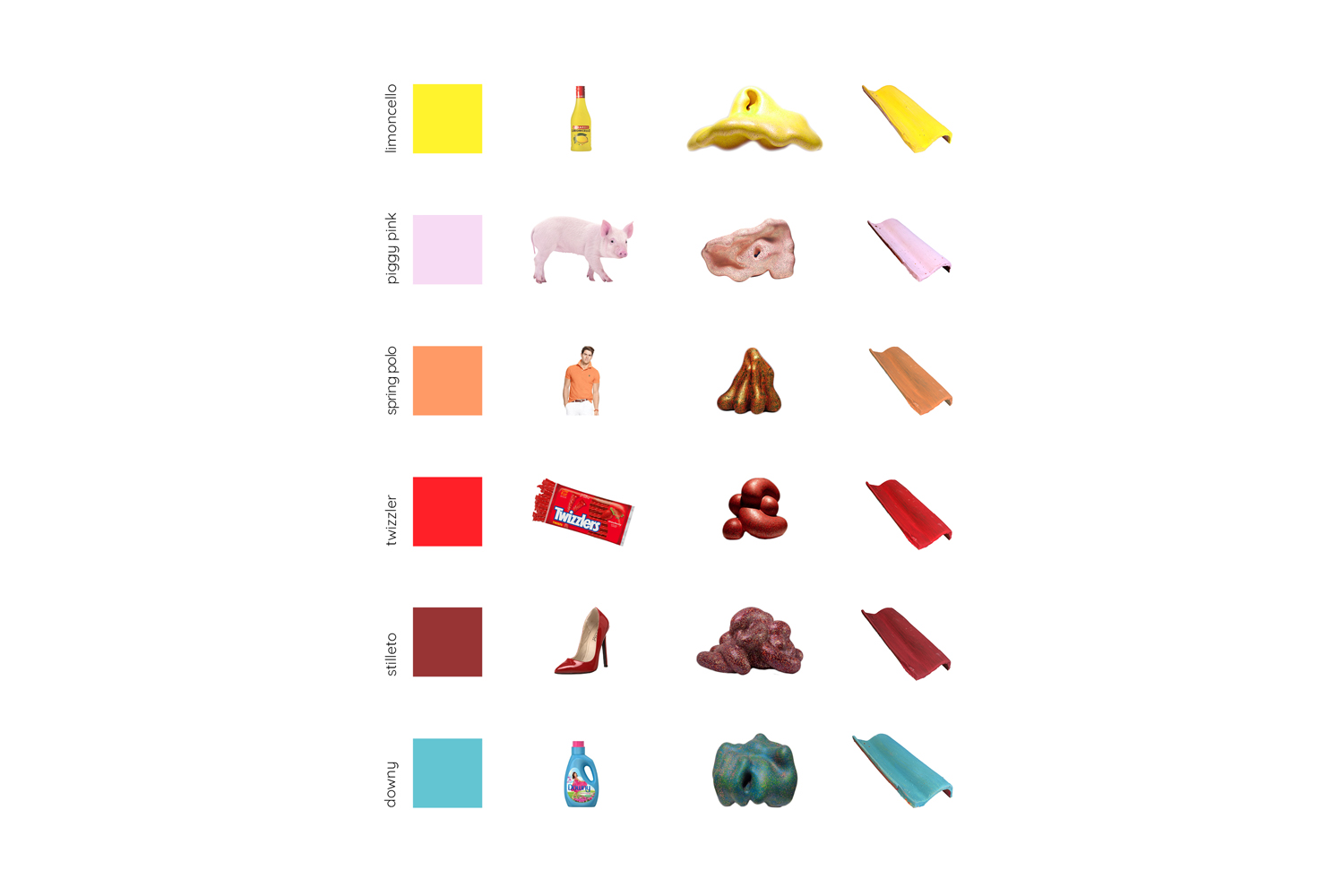

KEN PRICE, HOME DEPOT

In the spring of 2017, Benzi, Anna, and I took an elective class on ceramics, as a much-needed counterbalance to and respite from the intesity of thesis. With emphasis on material studies and form fabrication, we quickly became fascinated by the extreme differences in cost, labor, and percieved artistic value of ceramic objects occupying the two ends of the consumer spectrum, despite the underlying similarity of material.

1.01Price and Pricelessness

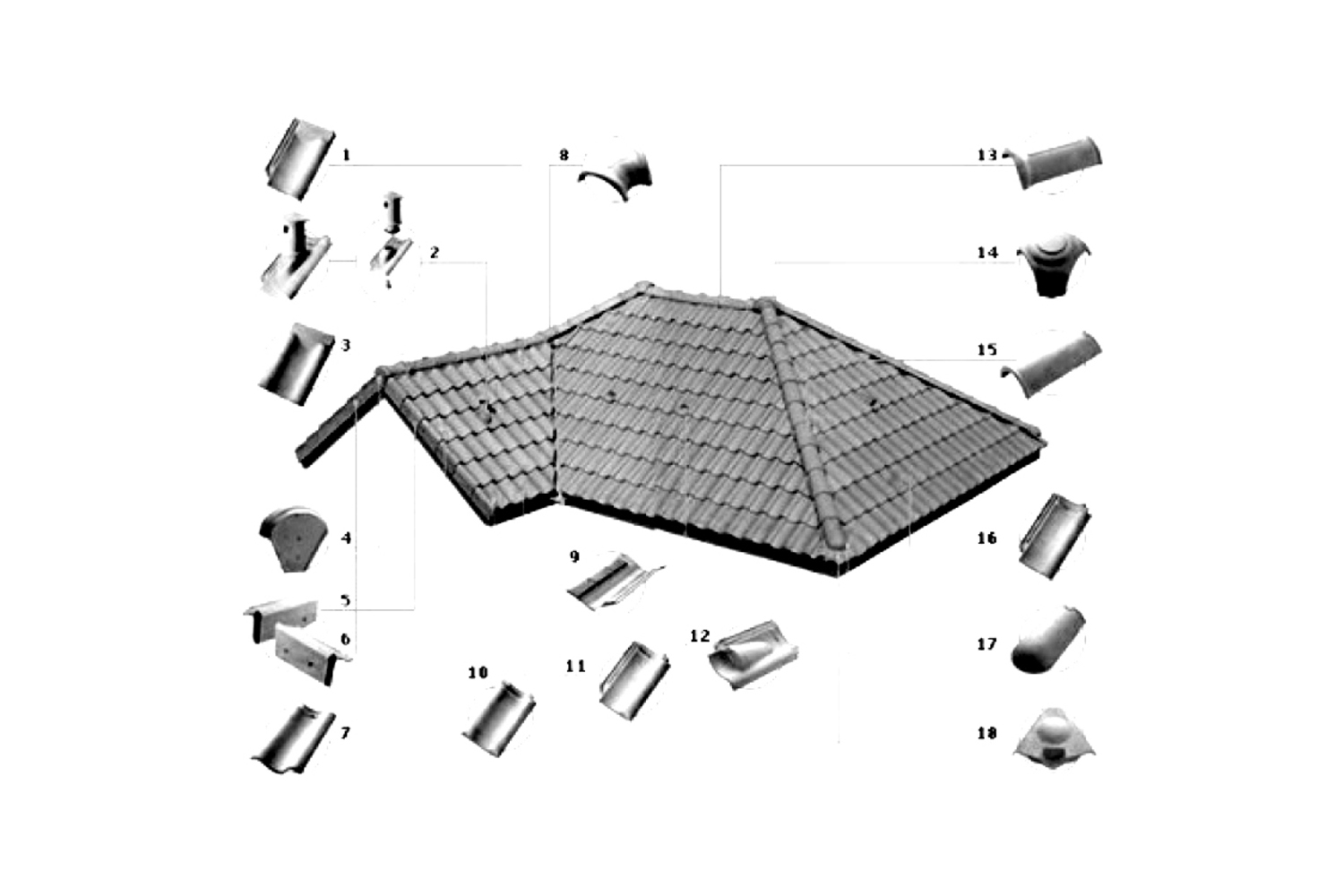

On one side sits the glossy, dappled, suggestively amorphous solid clay sculptures of native Angeleno Ken Price, their bespoke finishes produced through the time-intensive, labor-intensive process of hand sanding dozens of layers of meticulously applied acrylic and lacquer, with a sticker price falling upwards of $200,000. On the other, made in mass and bought in bulk, unscrupulously generic and ubiquitously deployed, lie your terracotta roof tiles, Spanish S, readily available for $4.72 per square foot at Home Depot.

At a trading rate by weight at 5-8 tiles per sculpture, does the additive cultural and consumer value of Price's sculptures really appreciate the underlying ceramic material by 1000%? The sculptural object - complex in form but simplistic in its 'assembly' from a single block of clay - is perfect foil to the Spanish tile's standardized shape in a comprehensive catalogue of specific parts. For every gabled intersection, ridge joint, dormer window, exhaust pipe, and end cap condition there is a tile. Their extruded forms are functionally driven and assembled over conventional roofs: an underlying methodology of construction that leaves room for the exuberance of expression captured in Price's sculptural works without compromising the tectonic performance of standardized production.

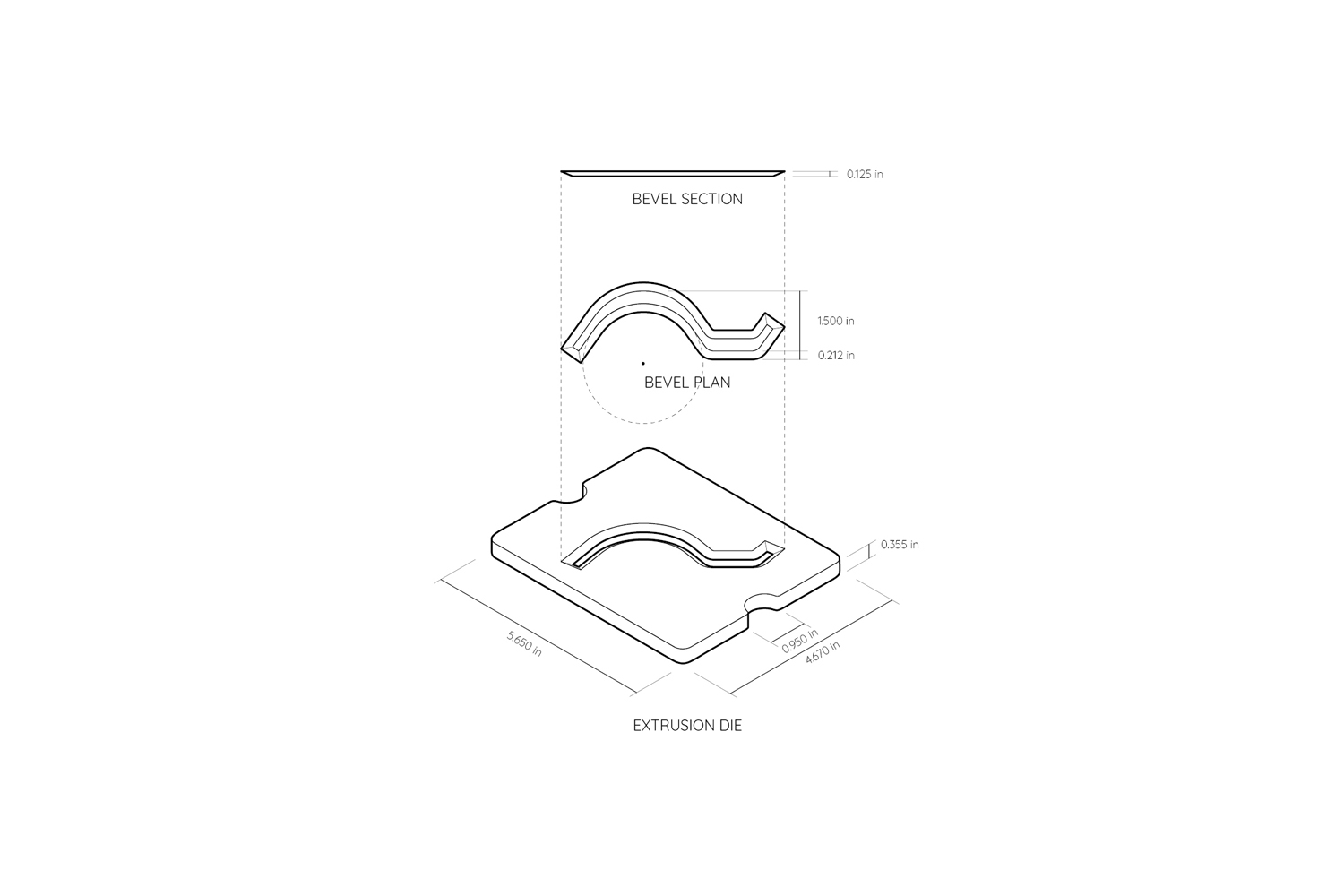

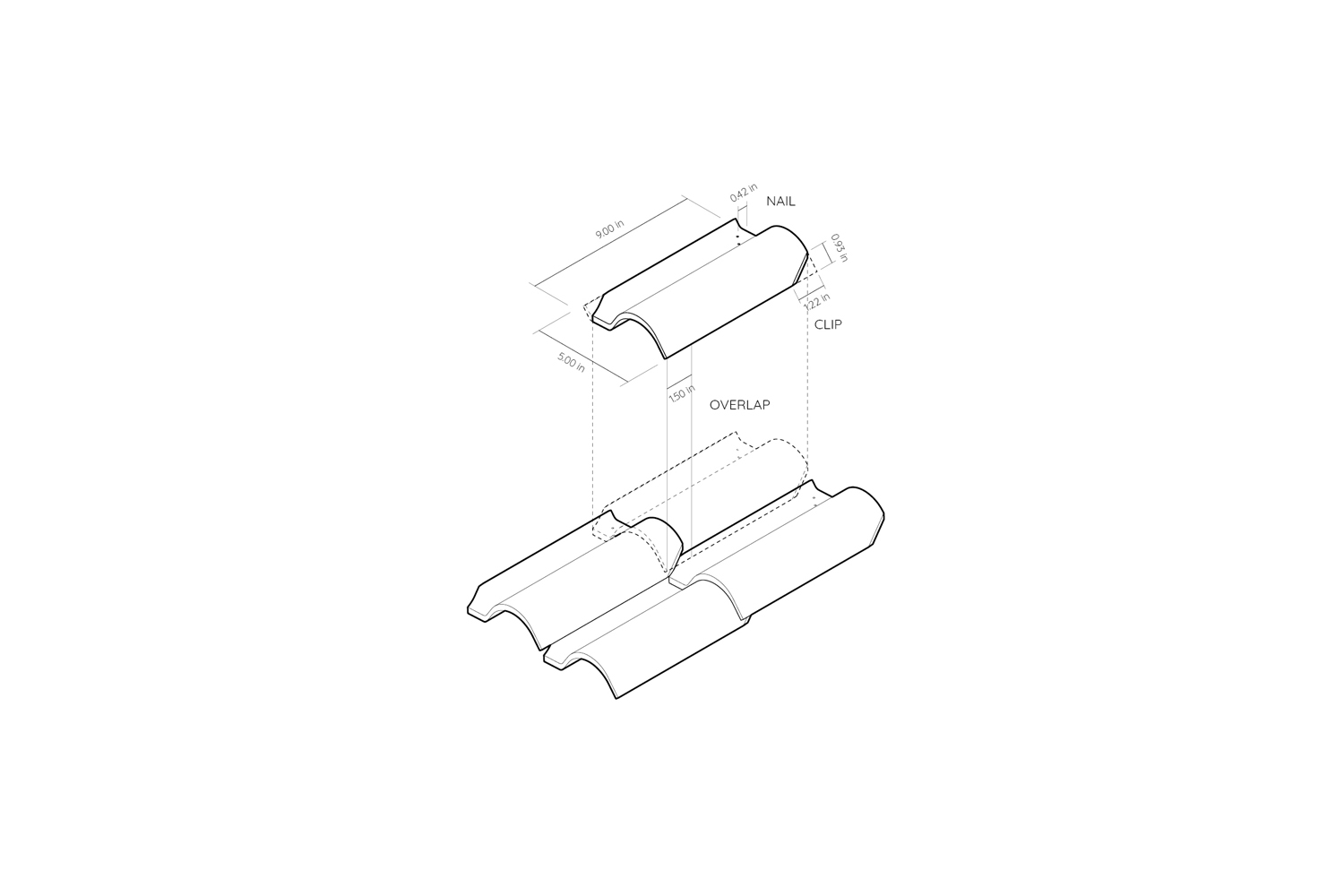

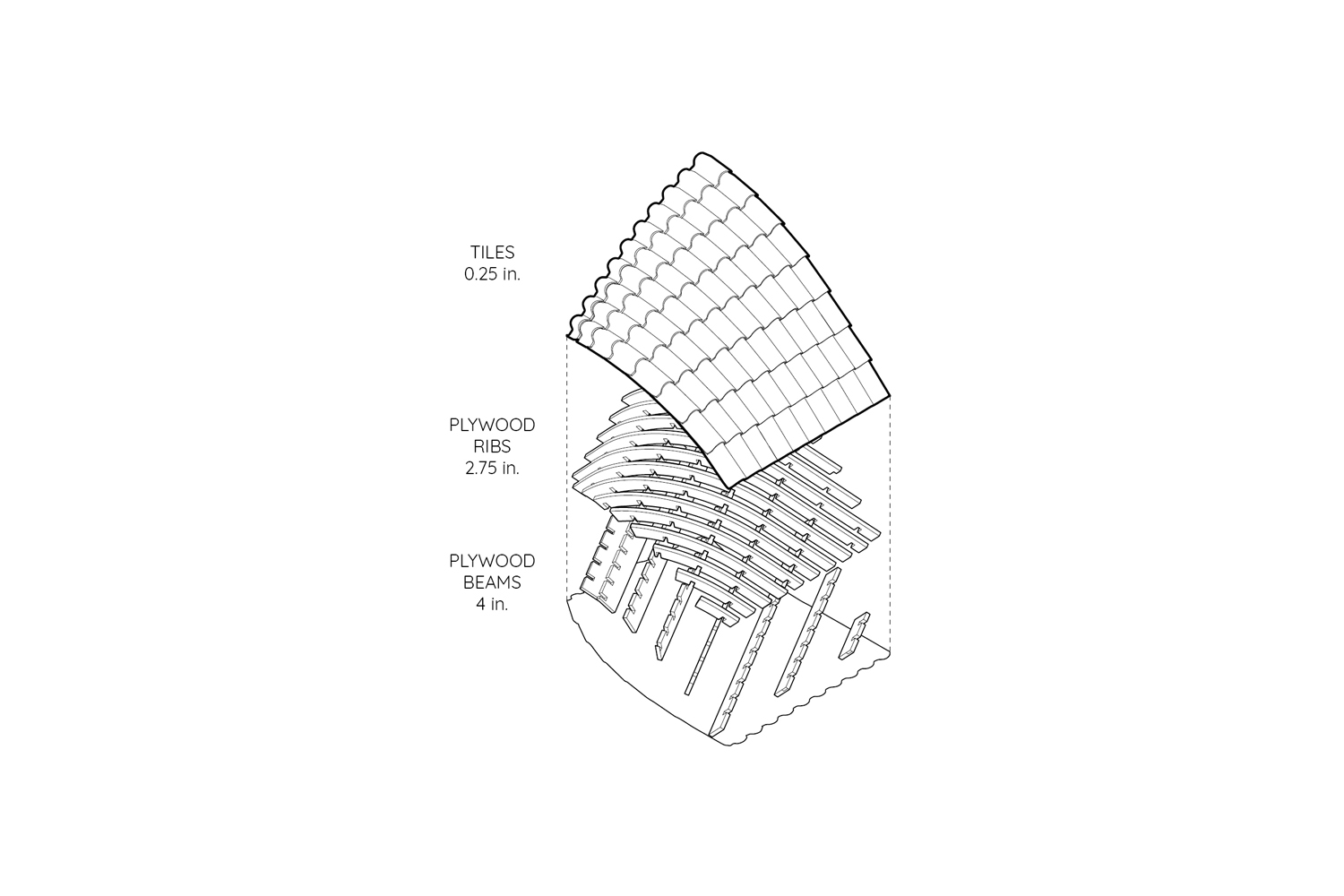

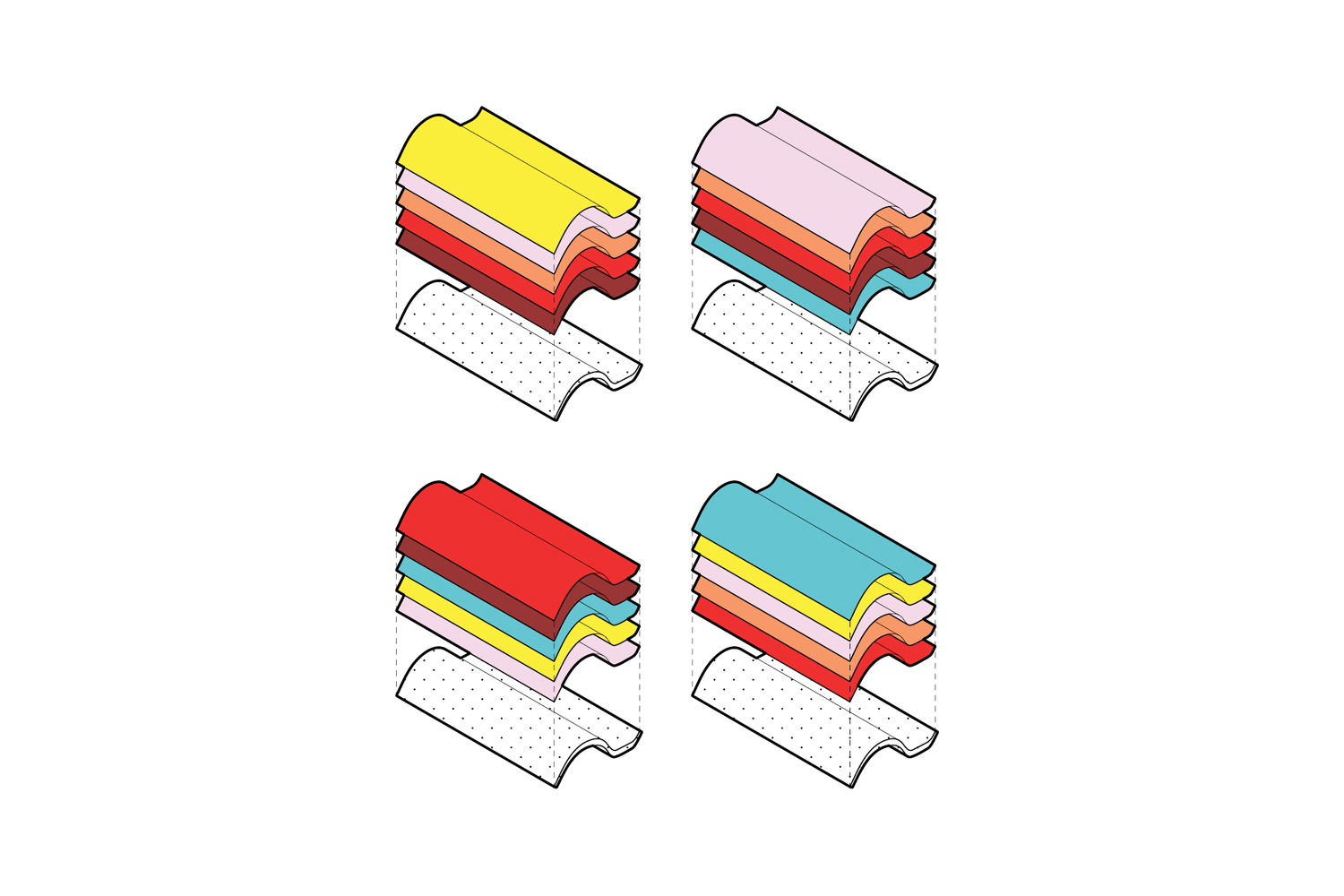

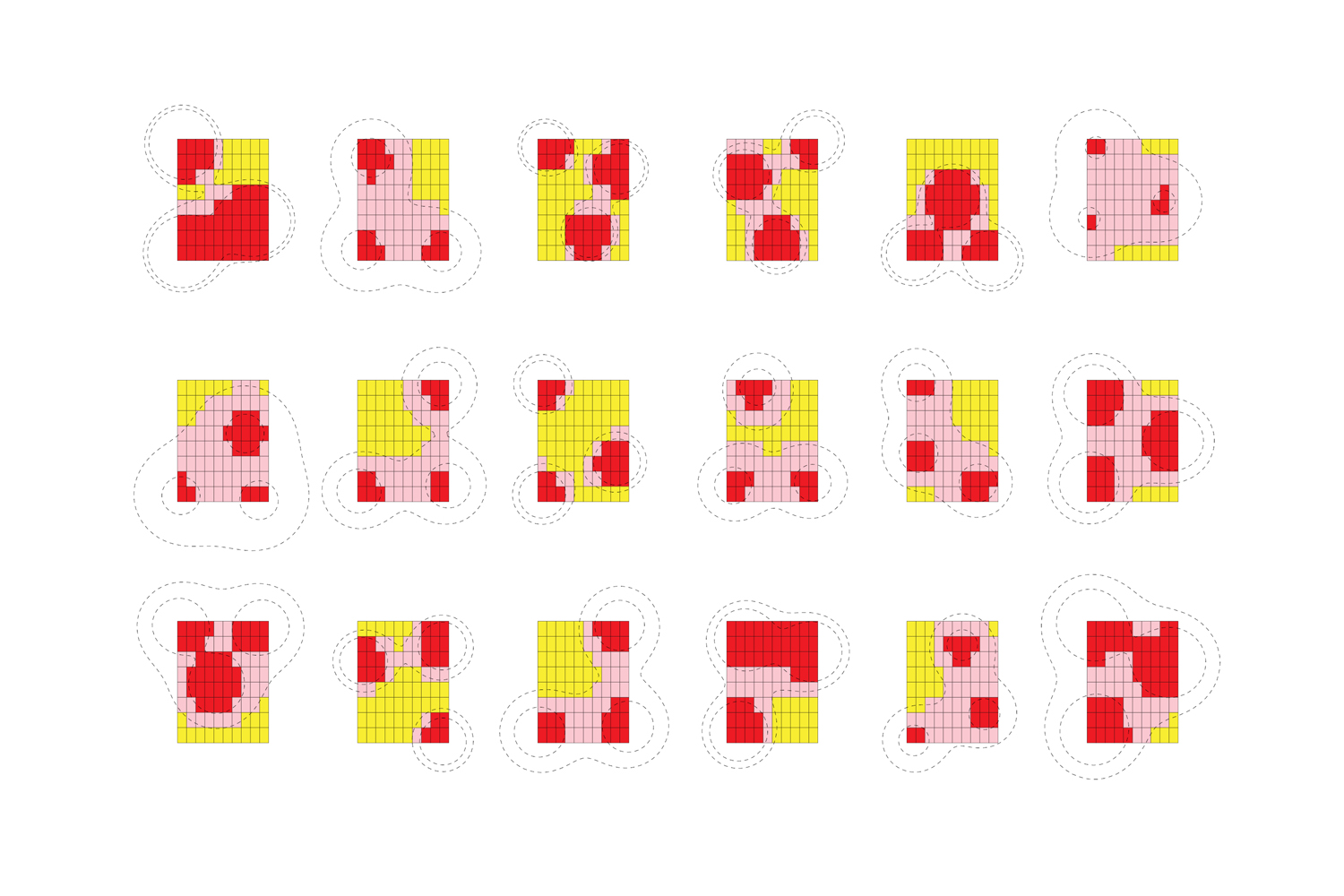

1.02Ready-to-Build, Fall/Winter 2017

To us, a Ken Price x Home Depot collaboration would see the rules, regulations, and dimensions of tile construction re-imagined for curved roofs that approach their own bespoke sculptural quality at distance, on the scale of the assembly rather than the clay unit. Without changing the standardized production of the terracotta S tiles, which are extruded from a milled plastic die and cut into fixed lengths, we allow for a small consistent angle deviations in how the tiles overlap when they are nailed together. Propagated over several rows, the points at which these tiles are fixed can be extrapolated into curves which describe a ruled surface. The punchline becomes a structural moiré, where the skewed grid of the substrate to which the tiles are affixed is then layered obliquely across their supporting beams, obfuscating the construction logic of the overall assembly. This system of tile to substrate to beam is flexible enough to accomodate a range of ruled and flat surface variations, capable of generating an entire taxonomy of roof-objects.

In ceramic roof construction, forms are limited by the complexity of standardized tiles and the assembly of their scaffolding. They are particularly good at cladding gabled roofs, as they are just tilted planes. However, there exist singly-curved geometries such as conic turrets and cylindrical barrel vaults, which can be undrolled into courses without distortion. This project exploits the combination of flat to singly-curved geodesic surfaces while using an "off-the-shelf" building technique: an assembly of linear beams and curvilinear ribs which are spaced for diagonally- coursing tiles.

1.03Abrasive Actions

"Price carefully begins to sand the surface of the painted sculpture. As the sandpaper removes the paint from the high points of grog, the first buried color appears. Further sanding reveals deeper layers of the stratified paint. Violet surrounds orange, which surrounds blue - all at a jewel-like scale. Price sands an area down to a point where the color array seems right and then proceeds to sand down every square inch of the piece to exactly the same layer. The result is a modulated array of colors that seems to have emerged through a natural, non-human process."

Price laboriously prepares the surfaces of his sculptures with a variety of instruments, resembling dental tools, before sponging down the clay to reveal hard bits of ceramic. Each sculpture is coated in about fourteen layers of acrylic, which in combination with the grog reveal varying gradations of color schemes when sanded. Our low-fi finish simplifies this process into 5 coats of underglaze in cyclical order, so that similar hues are at times adjacent and at times sandwiching brighter complimentary colors, to enhance each tile's depth and vibrance in an Albersian mode of changing the perception of a hue simply by virtue of shifting its neighboring color context. The top layer is dominant in the scheme, with the secondary layer as the main highlight color that is exposed during the sanding process. Each color thereafter adds subtle contrasting tones to these top two layers.

Without the curved surface geometry of Price's sculptural forms to reveal subtle variations in color erasure, we settled on fast-paced process of spot-sanding multiple tiles simultaneously with a sand blaster. On the level of the assembly, metaball scripts produce many variations that emulate the voluptuousness of Price's sculptures and replicate the mottled effect on a macro level.

2

ONE NIGHT ONLY

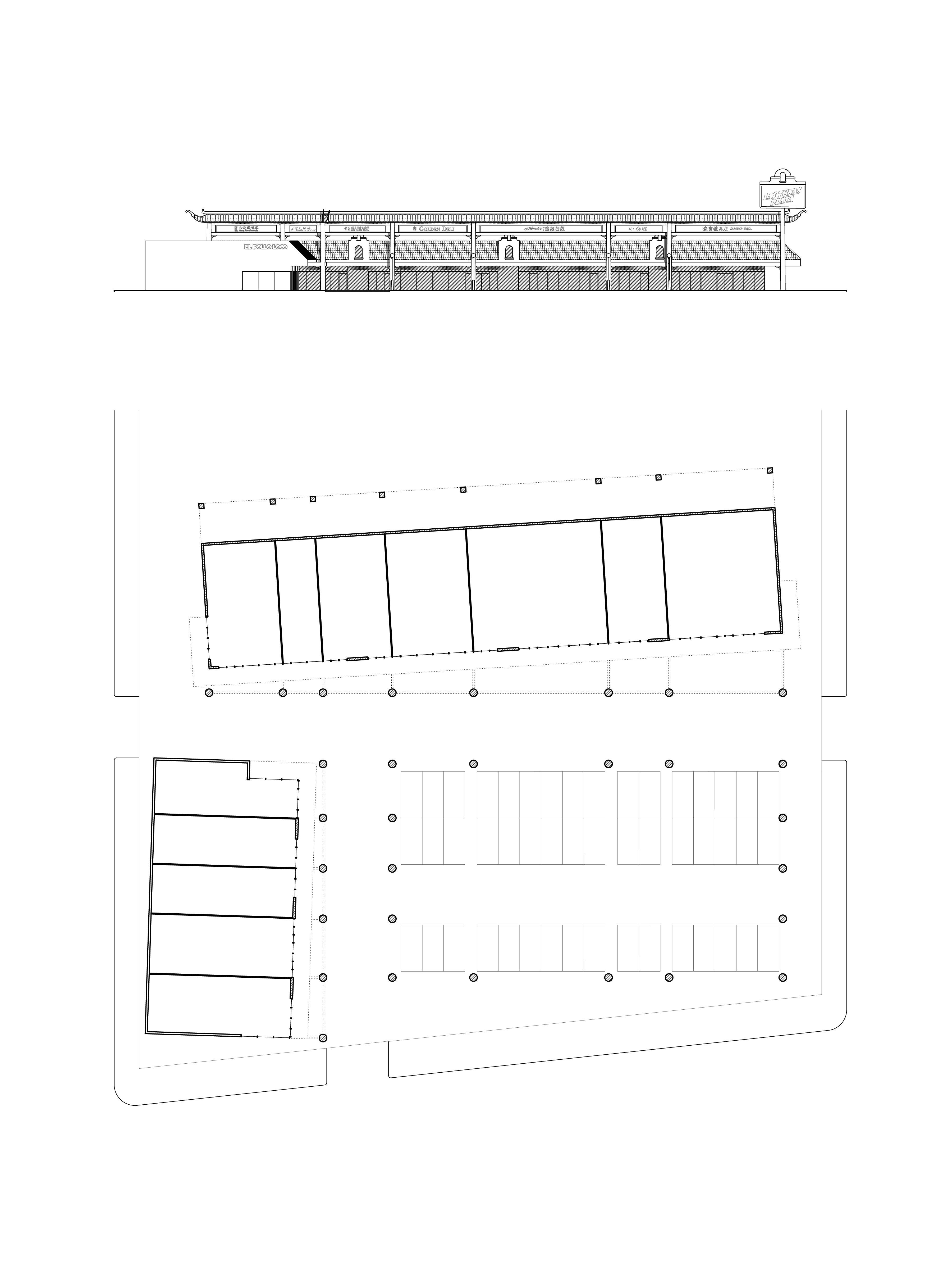

The second inaugural Dopium LA event, thematically titled ["DIMENSIONS"], was a one night only multi-sensory art exhibition at the A + D Museum in downtown LA. Originally marked for the Mandarin Plaza in Chinatown, the brief called for a site-specific showcase of cultural experiences and stories that have informed our foundations as artists. Our project, already inheriting from the built typology of the Spanish Colonial Revival style and the Los Angeles ceramic art movement, turned to the iconic tiling of Chinatown roofs and their neon-emblazoned gateways to set the scene for Dopium LA.

2.01Chinatown Colonial

Chinatown as we see it today was the playground and product of Hollywood set designers in the 1930s, intentionally flat in its architectural expression and saturated with the mise en scène of eastern exoticism. Through the decades, these shallow copies of traditional vernacular began to adopt a language of their own through various permutations of form and finish, with blazing neon silhouettes running along curved ang beaks and ridged ceramic tiles, each serving as pure ornament against a backdrop of stylized facades. It is this spirit of vernacular expression - one that is protean, one-dimensional, and impermanent by nature - in which we find discourse.

We want to mine these influences to offer future narratives for the rich appliqué of ceramics across the built environment. From the terracotta roofs of Spanish Colonial Revival homes, to their geometric and colorful transformations across Chinatown, mixed in with the finish techniques of LA-based ceramics artist Ken Price, we hope to layer these methods of both high and low cultural production to forge new conversations between the surrounding tiled roofs and a more comprehensive understanding of their sources. As a cross section of Southern California aesthetic traditions, our prototype borrows these techniques to create a more synthetic vernacular expression in the Mandarin Plaza.

2.02Ceramic Scenes

As a group of designers, we are attuned to the imaginative potential of these forms and the make-believe environments they evoke. Our proposal, originally slated to sit on the roof of an adjacent building, found its home slumped over a seating bench in a domesticated scene that emphasized mood through lighting as day turned into one night only at A + D.

: An architecture of extraction.

| TYPE | thesis |

|---|---|

| YEAR | 2017 |

| FOR | m.arch I |

| SITE | johannesburg |

| TEAM | andrew witt (advis) |

1

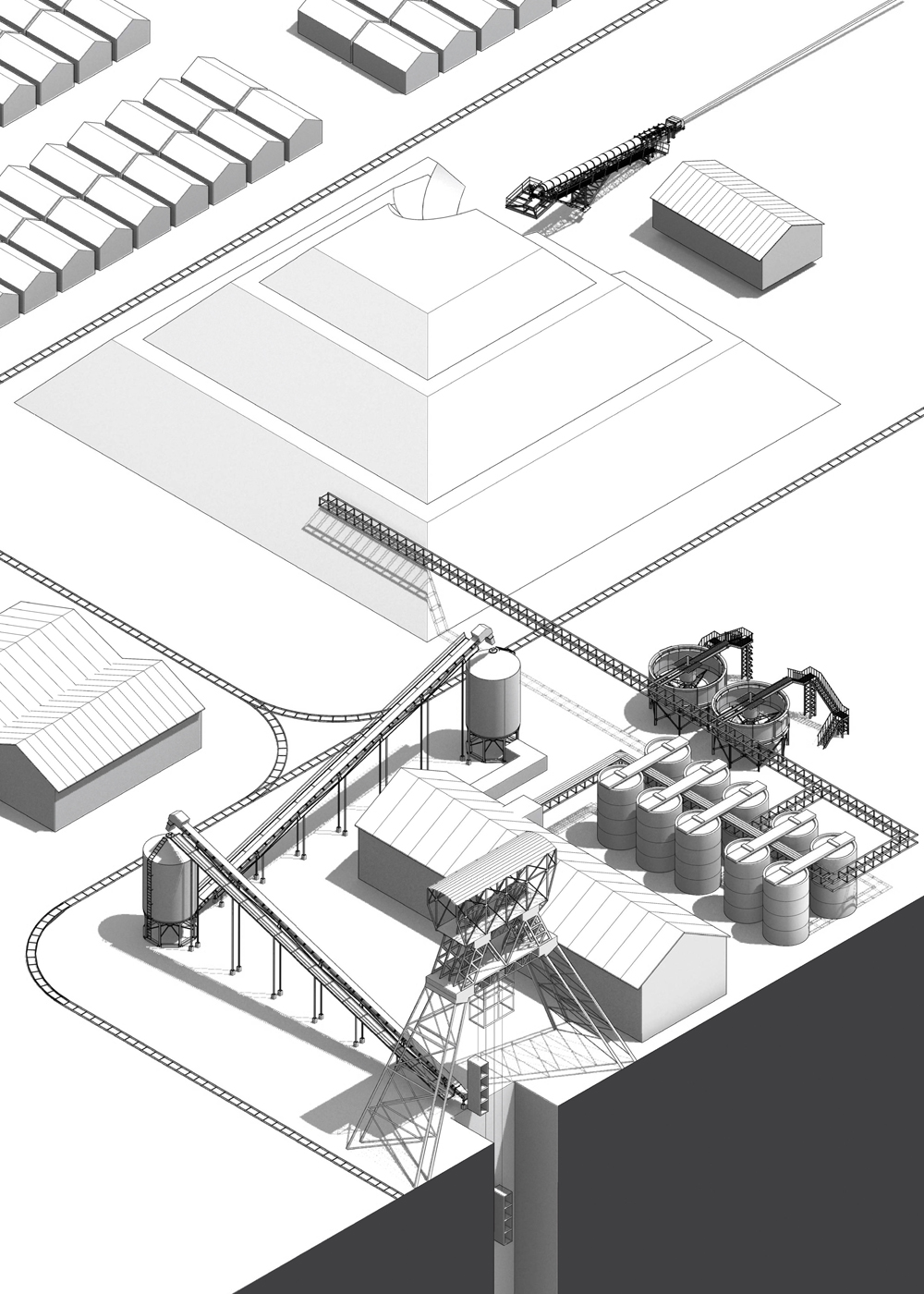

CAPITAL, COMMODITY, AND INFRASTRUCTURE

The narrative of post-industrial capital, in so far as it is capable of transforming at scale the material landscape of wealth into self- reinforcing structures of organization and power, is reaching a critical point with the advent of modern urbanization. As succinctly surmised by Mark Weiser in his 1991 essay in Scientific American, “the most profound technologies are those that disappear...they weave themselves into the fabric of everyday life until they are indistinguishable from it”. Contemporary infrastructures in this sense are radically reshaping the processes, politics, and aesthetics of commodification and commodity fetishization that have been the hallmark of capital accumulation in the 20th century. In looking at the material foundation of capital and currency following the industrial revolution, this thesis nosedives into the relationship between power, capital, and the built environment through a case study of the global dynamics surrounding the implementation of the gold standard in the early 1800’s, and the unprecedented metamorphosis of Johannesburg’s urban landscape that resulted in the following century.

1.01Value, in perpetuity

To situate the terms ‘capital’, ‘commodity’, and ‘infrastructure’ within a Marxist framework, capital is defined as the accumulation of wealth specifically through the process of circulation - a dynamic driven by the difference between a commodity’s use value and its exchange value. The capitalist then understands this value as being in constant motion, where profit is generated through perpetual reinvestment and consequent augmentation of exchange value. The nature of this value-added exchange is then contextualized through how one chooses to define the term ‘commodity’; and indeed, the chasm between commodity as it first appears in Das Kapital and as it is currently understood in the global markets is quite extensive. To Marx, commodity was “an object outside us, a thing that by its properties satisfies human wants of some sort or another”, and where “the nature of such wants, whether, for instance, they spring from the stomach or from fancy, makes no difference...neither are we here concerned to know how the object satisfies these wants, whether directly as means of subsistence, or indirectly as means of production”. This definition is metaphysical in disposition, and is concerned less with the tangible qualifications by which a specific externality is commodified than it is with the understanding that commodification is a process implicitly tied to human desire. As such, desire being a fickle beast, the commodity is monadic as a unit endowed with perceptual virtue, and it is this appended quality that gains in value through transformations of exchange by social and political forces.

1.02Consumptive futures

Contemporary economics, however, defines the commodities trade far more tangibly: such objects are typically uniform in pricing across many markets, are used in the production of othergoods, and can be extracted or grown and traded in sufficiently high quantities. These traits allow them to support extremely liquid markets in which futures and options are often sold to protect both producers and consumers against fluctuations in price. In this context, the commodity necessarily exists on a global scale, and its value in trade is defined not by a consistent growth in exchange value but rather by the ease with which they can be converted into money through their use in other, more refined products. Thus cocoa, copper, wheat, oil, and coal qualify whereas diamonds, due to their inconsistencies in quality, and natural gas, due to its predisposition for price determination through long term regional contracts, do not. The modern commodity exists in material form only briefly; its primary purpose is to be liquidated as quickly as possible for as much as possible. The selling of futures - the functional equivalent of the Marxist exchange value - is now complete in its disembodiment from the physical realities of the object itself, acting as a stand-in independent from the actual volume of material being extracted or produced. Where the Marxist perspective portrays the commodity as an object with appended metaphysical value, in perpetual circulation, the economics of today suggest they are transient one-way pipelines from production at scale to diversified, globalized consumption.

1.03Material mediators

In this discourse, the term ‘infrastructure’ exists purely in relation to the flows that enable capital accumulation through the production and consumption of commodities. Maria Kaika and Erik Swyngedouw identify technological networks as the “material mediators between nature and the city; they carry the flow and process of transformation of one into the other”. The process of assigning market relations to socially metabolized goods is fundamentally dependent on the process of fetishization, which in the Marxist sense is the quantification of the qualitative that allows for abstraction to take over. The fetishized commodity supplies its own ideology in the market, and allows for augmentations of its exchange value without revealing the socioenvironmental circumstances of its production.

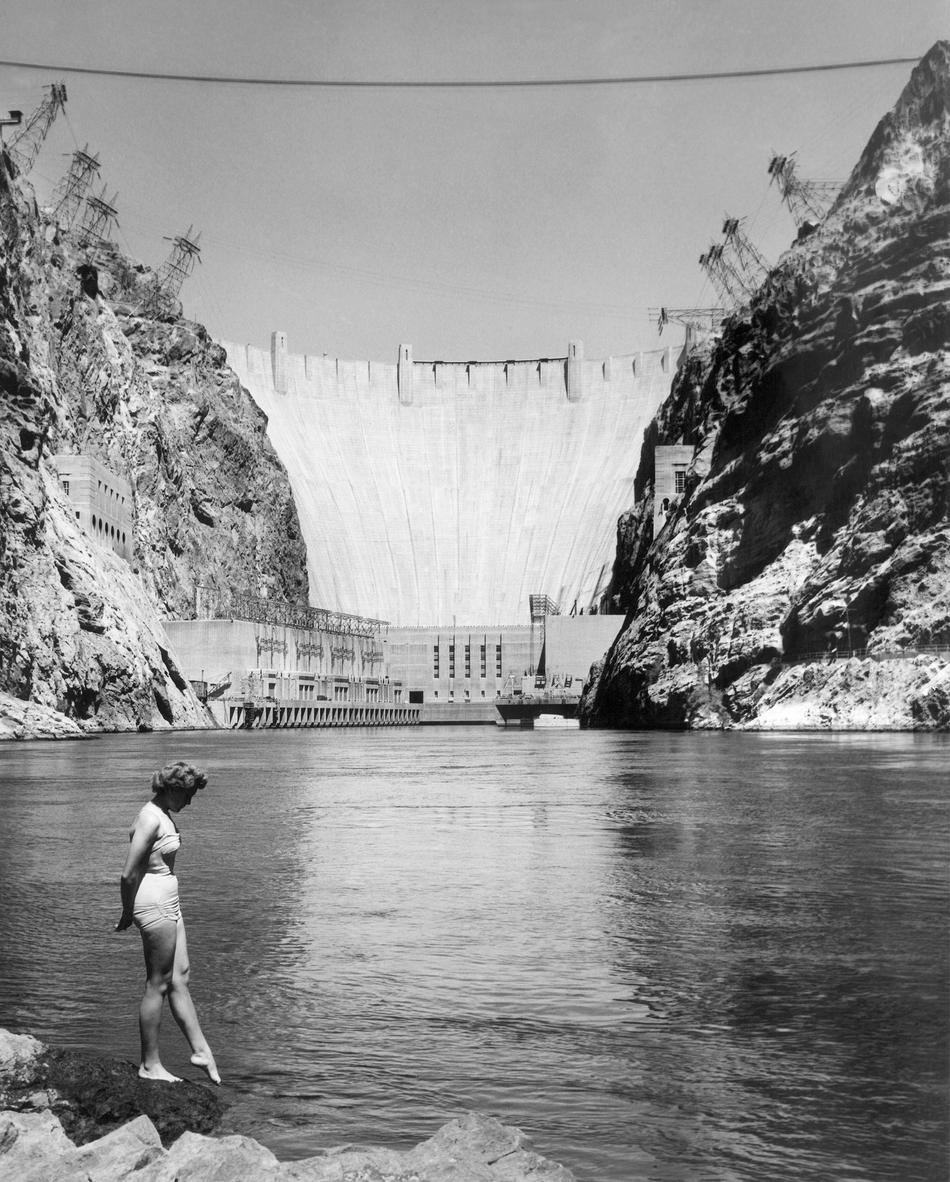

1.04First monumental, then mundane

Commodity fetishism in the modern era merged economics, politics, and culture to materially enact an ideology of progress, resulting in behemoth infrastructures which served as monuments to engineering and technological progress. In the span of a decade from 1904-1914, the construction of the Panama Canal resulted in the excavation of more than 130 million cubic meters of earth. The Great Depression gave birth to the Hoover Dam, impounding Lake Mead for hydroelectric power and containing more than 3.3 million cubic meters of concrete. These megastructures operated at a scale unfathomable to the human body, iconic in both size and impact. With the abandonment of this techno-optimist ideology following the abysmal living conditions characteristic of post-industrial cities and the mechanical destruction of the two world wars, came the erasure of urban networks from visible, physical space; a transition from the monumental to the mundane. Contemporary urban infrastructures are invisible: pipes, cables, electronic waves that sever the connection between the social transformation of nature and the process of urbanization. In this sense, physical infrastructures are the residue, the material byproducts of the process of capitalism, viewed only as instruments in the service of additional value extraction, and can be extended to include the material city itself - and embedded in this material manifestation are power dynamics which facilitate the flow of capital, often in service of those with purchasing wealth. In our globalized economy, these flows transcend geographic and political boundaries, directionally fixed from sites of extraction to territories of mass consumption.

1.05Infrastructure in motion

Here we stumble upon a fundamental paradox of capital as it relates to infrastructure: how does one

reconcile the dynamism of capital in perpetual motion and fluctuation with infrastructur that is

static and immobile in space? One could argue that this tension manifests as the creative destruction

of the built environment and ceaseless restructuring of scale economies, characteristic of the

cityscape in advanced capitalism. Instability, in the urban context, thus occurs when a paradigm shift

in capital flow commands a radical restructuring of the physical infrastructures that must adjust to

enable its realization. From this several questions arise: how does the erratic flow of capital affect

the colonization of nature? How can one intervene in the static, built environment to influence these

flows, either to stabilize or stimulate its corresponding capitalist system? How will infrastructure’s

legacy manifest itself both materially and aesthetically upon future cityscapes?

Identifying infrastructures as being primary, secondary, or tertiary respective to its corresponding

role in extraction, commodification, and information distribution, then commodification with the

emergence of late capitalism shows tertiary infrastructures with ever increasing scale and scope,

inversely related to their presence in physical space. The long timescales and inertia of built

infrastructure, when contrasted with the immediacy and rapid evolution of digital information and

boom/bust cycles poses significant point of investigation for this project. In looking at the

post-industrial evolution of currency from the gold standard to the digital, we can perhaps draw some

conclusions about how modern societies can develop resiliency in the face of rapid capital flows as we

mature through the age of information.

1.06The Gold Standard

Arguably the most classically transformative paradigm shift in the history of currency, the

establishment of a formal gold standard among the major trading nations during the 19th century reveal

the scale and scope to which capital flows can reshape the urban and its subsidiary landscape. Gold has

existed as a form of currency since as early as 610BC, but it wasn’t until the era of colonization and

rapidly expanding global markets that the metal became incongruously cumbersome to transport across

vast distances. Where before the value of the gold coin was embedded in the material of the coin

itself, the introduction of the gold standard allowed for a more efficient representation of value - in

this case, paper currency - that was still fixed upon some definite quantity of gold.

This new mode of representation not only facilitated the global trade by establishing trust between

governments which could redeem any amount of paper money for its value in gold, but it also kickstarted

a global feedback loop between gold mines, gold markets, and government. Burgeoning multinational trade

heightened demand for gold to back the standards in the US and Europe, especially gold which could be

mined as cheaply as possible to maximize the profits of colonizing nations. In turn, as their wealth

grew so too did the volume of trade, propelling the demand for gold ever higher. Britain was the first

to adopt a gold specie standard in 1821, followed by the United States and Germany in 1873.

1.07Critical instabilities

This system, however, proved unstable as each injection of new gold into these economies also meant a

drop in the value of gold and their corresponding currencies. Instability reached critical thresholds

with the advent of the first world war, when the standard was suspended to enable bulk printing of

paper currency to fund military involvement - instigating a period of hyperinflation as the value of

currency was no longer stabilized to a regulated material form. The standard failed once again during

the Great Depression, as investors began trading in currencies which subsequently raised the value of

gold and promoted widespread hoarding during the fallout of trust in American banking institutions

following the stock market crash. An equally powerful counterswing instigated by Roosevelt, in an

attempt to stymy depletion, then resulted in the largest global consolidation of gold stock in the

Federal Reserve. Because of this majority share, the US dollar had become the de facto world currency

by the 1944 Bretton Woods Agreement, which fixed all exchange values in terms of gold.

This marked the beginning of a new dynamic in gold’s role as a commodity: where before its use value

lay in the ease with which it could be liquidated (exchanged for cash), this function has now been

replaced by cash itself. Instead of stockpiling gold, other countries began stockpiling the US dollar,

thus turning a paper currency into a commodity, where its value is not fixed to some quantifiable

material but rather to the scale and scope in which it is used. Though the gold standard officially

ended on August 15, 1971 when the ballooning value of the US dollar due to its role as the linchpin

of the world economy could no longer be backed by its gold reserves, and the Fed could no longer

redeem dollars with gold, the metal continues to embody an asset of real value in the global social

conscience, as exemplified in its purchase during periods of recession and inflation.

2

CITY OF GOLD

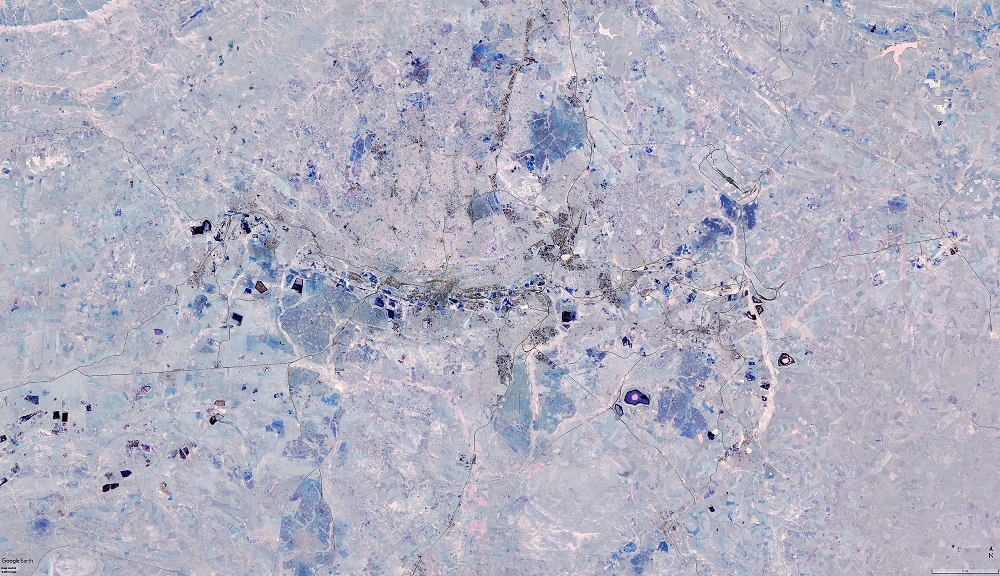

The ramifications of a globalized gold market as geopolitical infrastructure at the source of extraction and production are profound. A fascinating dive into the gold supply chain during the first four decades of the 20th century pinpoint the Transvaal region of South Africa as the supplier of 35% of the world’s gold production, and the approximately 50,000 tons of gold extracted since the end of the 19th century account for almost half of all gold ever mined through the course of human history. The transformations in this area, in particular the rapid conversion of a primarily agrarian society into the largest and richest metropolis of South Africa and the violence exacted upon its land and people, are inextricably tied to the politics behind the establishment and subsequent turbulences of the gold standard.

2.01As Above, So Below

In the summer of 1886, prospectors struck gold on a small farm called Langlaate. This was the

Witwatersrand Reef, which extends east-west for 400 kilometers and runs for some 5,000 meters below

ground. Soon prospectors and migrant workers came and set up small mining camps wherever gold was

struck, and Langlaate merged with clusters of other camps to form what is now the city of Johannesburg.

Growth was explosive: in the year following discovery, the Reef in its entirety was estimated to

contain some 7,000 people, less than half of which lived in Johannesburg itself. Not four years later,

Johannesburg’s population had multiplied ten-fold, and by 1891 approximately 102,000 people resided in

the city. The circumstances of Johannesburg’s formation, and the exponential growth that followed, is

written permanently into the urban fabric. Previous gold discoveries in the Transvaal were all alluvial

and thus transient in nature, and so the original subdivision of land in Johannesburg’s first camp

clusters were closely spaced, typical of 19th century mine camp planning. By the time it became known

that the Reef ran both deep and wide, the burgeoning class of migrant workers had already drawn lawyers,

shopkeepers, and traders that converted the camps into more permanent buildings, crystallizing the

original partition scheme into what is now Johannesburg’s central business district.

Transportation and other infrastructures materialized quickly within this period, with piped water,

electricity, and telephones appearing in the first two years, and South Africa’s first railway system

inaugurated by the beginning of 1890. Initially servicing the predominant east-west run of the Reef,

these infrastructures soon had to negotiate the mining waste dumps, sometimes deposited just meters

away from the mine entrances due to the initial ad hoc zoning restrictions, that resulted from a shift

into deep-level mining after surface outcrops ran low. The problem of waste was further exacerbated by

the low grade ore that characterized much of the Witwatersrand Reef, with some companies producing up to

200,000 times as much waste as gold: an issue that only worsened as time progressed and deeper

excavations were made to reach new deposits.

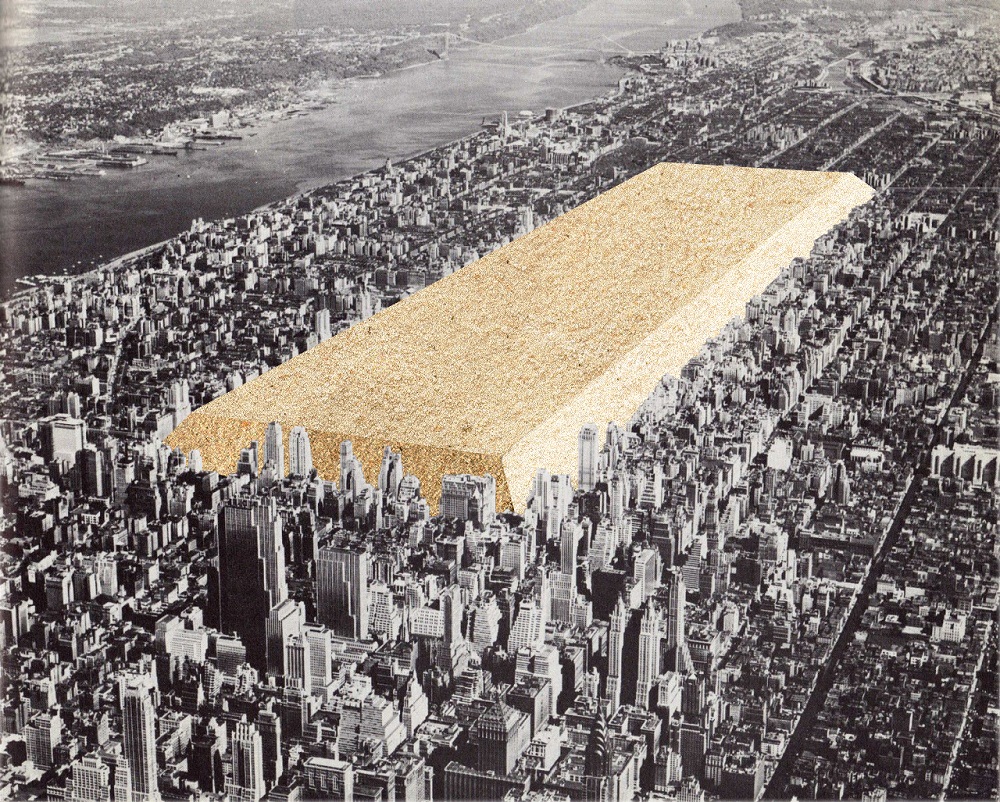

2.02Landscapes of waste

Today, south African mining companies remove up to 7,500 tons of earth to produce one standard gold

bar’s worth of product. Put into perspective, given that Johannesburg roughly produced a hypothetical

40% of the gold in the US reserve at its peak, the equivalent waste mound would cover the entire

footprint of Central Park with the height of One World Trade Center, four times over. As railway and

automobile infrastructures continued to mature over the next few decades, connecting the sites of gold

extraction with the major ports of South Africa for export, the tight weave of transit networks and

waste formed a permanent and prominent belt along the east-west axis of the city and its subjugate

landscape, splitting it into two distinct, unequal halves.

The material residue of gold mining in Johannesburg in turn shaped the geospatial division of

socio-economic class, as delineated through the restructuring of power during the Second Boer War in

1899 and the apartheid era politics that followed. At the crux of these political upheavals was a

fundamental economic problem: how to make the low grade ore profitable? Deep-level mining required

advanced knowledge and expensive machinery, which shifted the landscape of extraction from small-scale

manual panning by opportunists at the onset to large-scale mining operations often owned by wealthy

corporations abroad. As the extent of Witwatersrand Reef became clear, so too did political tensions

over who would gain control of the lucrative resource, especially with the adoption of the gold

standard. Established by the Boers after Great Britain annexed their Cape Colony during the Napoleonic

Wars, the Transvaal and Orange Free State initially drew many foreigners to its borders with the

discovery of diamonds at Kimberley in 1866. Soon after the discovery of gold in 1886, the Boers

understood that they lacked both the manpower and the industrial expertise to develop the resource,

and so reluctantly allowed the immigration of foreigners, called uitlanders, to the Transvaal. Many of

these immigrants were English-speaking men from Britain, and soon their population challenged and

potentially exceeded that of the original Boer settlers, which precipitated tensions between the two

groups. In part driven by expansionist ideology, a notable proponent of which was mining magnate and

early gold investor Cecil Rhodes, as well as attempts to obtain full voting rights for the uitlanders,

the British attempted to raid the city in 1895 and finally gained control of the Transvaal and its

allied Orange Free State in 1902.

2.03Labor politics

With political ownership of Johannesburg’s gold established, it became clear that a profitable

enterprise would not have been possible without an abundance of cheap, unskilled labor from

disenfranchised migrant workers. The gold standard meant that pricing was internationally controlled,

and so any increases in operational costs could not be passed down to consumers through price

increases. The United States and other major European powers were major gold importers, and it was

also in their best interests to keep the price of gold low; thus, maintaining a constant supply of

cheap labor became a primary focus for both the Boer and British governments as well as the mine

owners. The following decades oversaw the political, social, and economic control of a huge

population of black Africans for this singular purpose. Through governmental and white acquisition of

land, harsh property taxes, and militaristic destabilization of neighboring African nations, the

development of the mining industry destroyed independent farming as a way of life and completely

reconfigured the socioeconomic structures of South Africa. A host of governmental policies spanning

the first four decades of the 20th century, ranging from the criminalization of job desertion and the

issuance of black passes to municipal segregation and the prohibition of blacks from buying or renting

land outside of designated zones, were put in place to prevent upward mobility and to promote

unemployment among the native African communities.

These policies also, by necessity due to the growing ratio of poor black laborers to white owners and

officials that by 1913 already more than doubled, created a distinct spatial separation of the groups

by discouraging interracial interaction outside of the mines themselves - a spatial pattern strongly

reinforced during the Apartheid era that followed. By the 1930’s, various black-only townships were

established on cheap land as a result of forced reallocation. Until that point, the lack of adequate

housing for Johannesburg’s vast working class resulted primarily in underserved, mixed-race

shantytowns near the city center that have been earmarked for removal. The Great Depression then

sparked a period of brief economic expansion, when the price of gold shot up due to the increase of

global demand with the abandonment of the gold standard, providing the South African government with

the funds necessary to separate and reallocate entire populations of black laborers. The largest

resettlement became what is today the township of Soweto, located just south of the central business

district, downwind from the massive mine dumps that divided the city. Here, land was cheap due to the

lack of transportation infrastructure, and as a result of the environmental hazards of living near

toxic waste dumps.

The next decades of Apartheid reinforced this pattern of isolating the wealthy, predominantly white

community into well serviced and well developed urban areas upwind of the waste belt, and relegating

the poor, black working class to sprawling shantytowns south - sometimes on top of the mounds

themselves. And just as racial segregation was territorialized within the urban and periurban areas,

the separation between urban and rural also became incredibly pronounced: stripping agricultural land

of its male workers and leaving their families to be supported by low mine wages in effect created a

dynamic where mine profits are maximized by policies that caused long term rural underdevelopment and

poverty still in existence today.

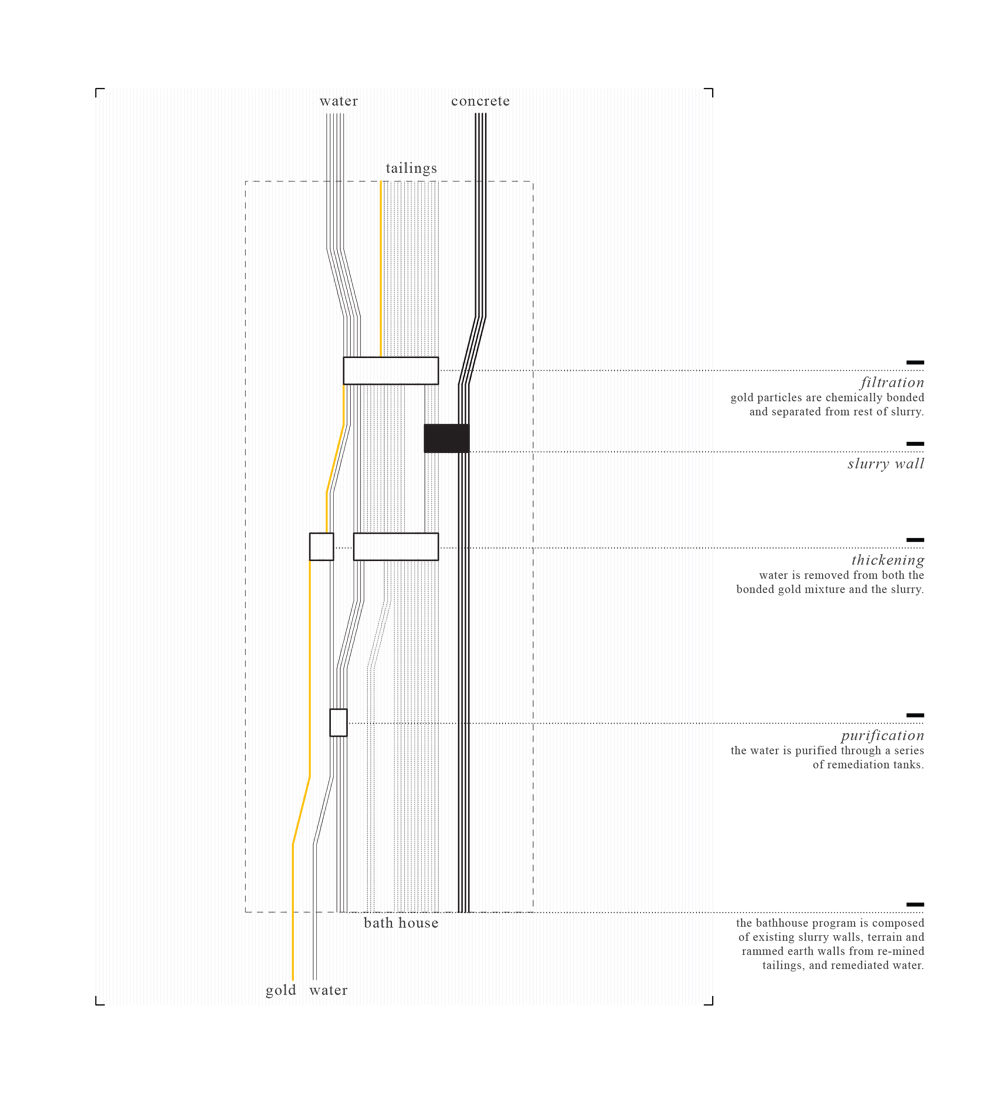

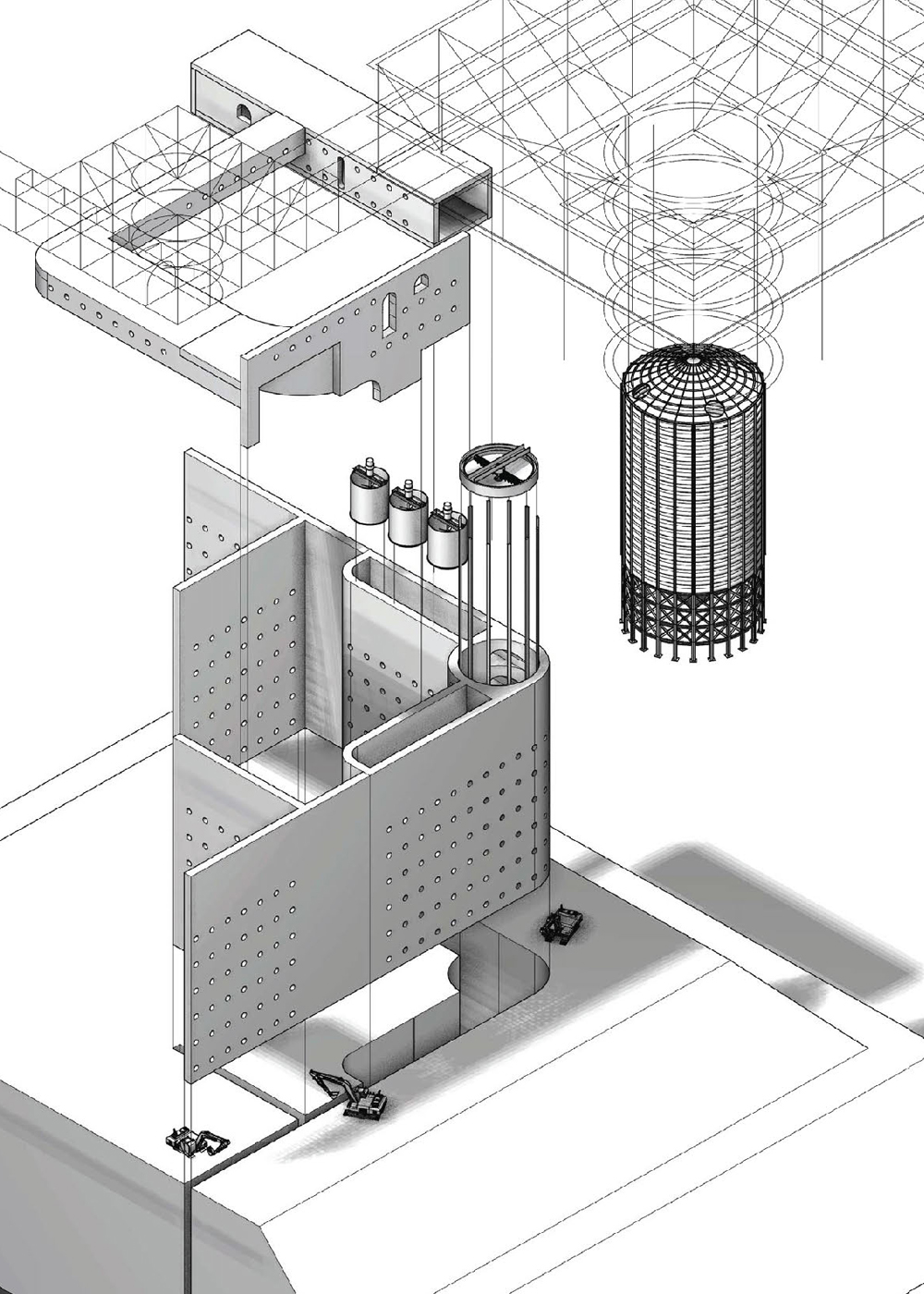

2.04Material erasure

South Africa’s economy, created from and dependent upon its gold mines, is now suffering from exhausted

deposits, increasingly expensive excavations, and extreme groundwater and air pollution from the

resulting waste. The large mining monopolies of the 20th century have dissolved into smaller South

African enterprises that, with new and more advanced refinement technology, have begun to re-mine the

waste dumps which contain small particulate gold unsuccessfully harvested in the century prior. Where

the original commodification process left distinct spatial geographies as delineated by these waste

dumps, their removal will instigate new dynamics within the urban and periurban fabric. Without process

regulation, all of the generated wealth will continue to flow into global markets while the original

mounds will be processed outside of the city and dumped in the periurban territory south of the low

income communities. Due to the waste belt’s proximity to the central business district, and with the

removal of waste leading to more favorable living conditions, the real estate value of the land will

rapidly increase and the nearby communities will gentrify. This land will most likely be developed into

higher income housing, and with the absence of biohazard waste to keep landvalue low, new urban lines

will be drawn as the previous poor communities who lived on and around the mounds will eventually

relocate even further outside the city to south of the new waste mounds.

Here is an opportunity for policy regulation and the built environment to respond to such a large

scale re-extraction of natural resources: by fixing the waste in place and rehabilitating it, this

power dynamic would be stabilized to create value for the poor communities while providing a buffer

for the rich, thus generating a more even distribution of wealth between the two communities while

maintaining urban densities. Thus the lesson from Johannesburg is through the material regulation of

extractive processes to fix them in place, which would reduce the turbulence of the existing

socioeconomic geography. By keeping the waste dumps where they are, but allowing for in situ

infrastructural construction within them, the waste belt would be less of a wall and more of a

mediator between the existing communities. The original infrastructural problem was a direct result

of Johannesburg’s rapid materialization, at enormous scales due to global demand for gold. To avoid

this mistake again, one must phase the remining process and allow it to happen heterogeneously

through space and time.

2.05Resilient futures

The instability of the gold standard is at its core based on the nature of commodification, where the

separation of use value and exchange value enables a flip flopping between their relative strengths.

The emergence of a gold standard thus coincided with the carving of new geographies of power, and each

subsequent turbulence in value reverberated down its infrastructural pipelines to its territories of

extraction and production. To effect change and to build resiliency into existing infrastructures, one

must regulate the process by which material extraction proceeds into capital.

What can we learn from the infrastructural instabilities in Johannesburg as a result of the capital

flow during the gold standard? In order to prevent the ad hoc rapid remining and large-scale

redevelopment processes from destabilizing the socioeconomic structure of the city, one potential

solution is to allow for the phasing of remining to occur concurrently with development at various

stages over time, while also regulating the process to happen heterogenously in space. The era of

centralized infrastructure is coming to an end; material stability must begin to rely on the

redundancies of distributed systems to survive our faster future.

3

A MANIFESTO

“Isaura, city of the thousand wells, is said to rise over a deep, subterranean lake. On all sides,

wherever the inhabitants dig long vertical holes in the ground, they succeed in drawing up water,

as far as the city extends, and no farther. Its green border repeats the dark outline of the buried

lake; an invisible landscape conditions the visible one; everything that moves in the sunlight is

driven by the lapping wave enclosed beneath the rock’s calcareous sky.”

- Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities

As systems-based thinking gradually reforms the domain of technical knowledge in the 21st century,

architects largely continue to abstract the building as an object unto itself: distinct from and not

beholden to the processes, materials, people, and consumptive forces with which every built structure

is in dialogue. This erasure of material memory leads to an accumulation of infrastructural residue

as old systems pass into obsolescence and extractive violence upon the landscape begins anew, leaving

behind an unintentional city and blind inhabitants.

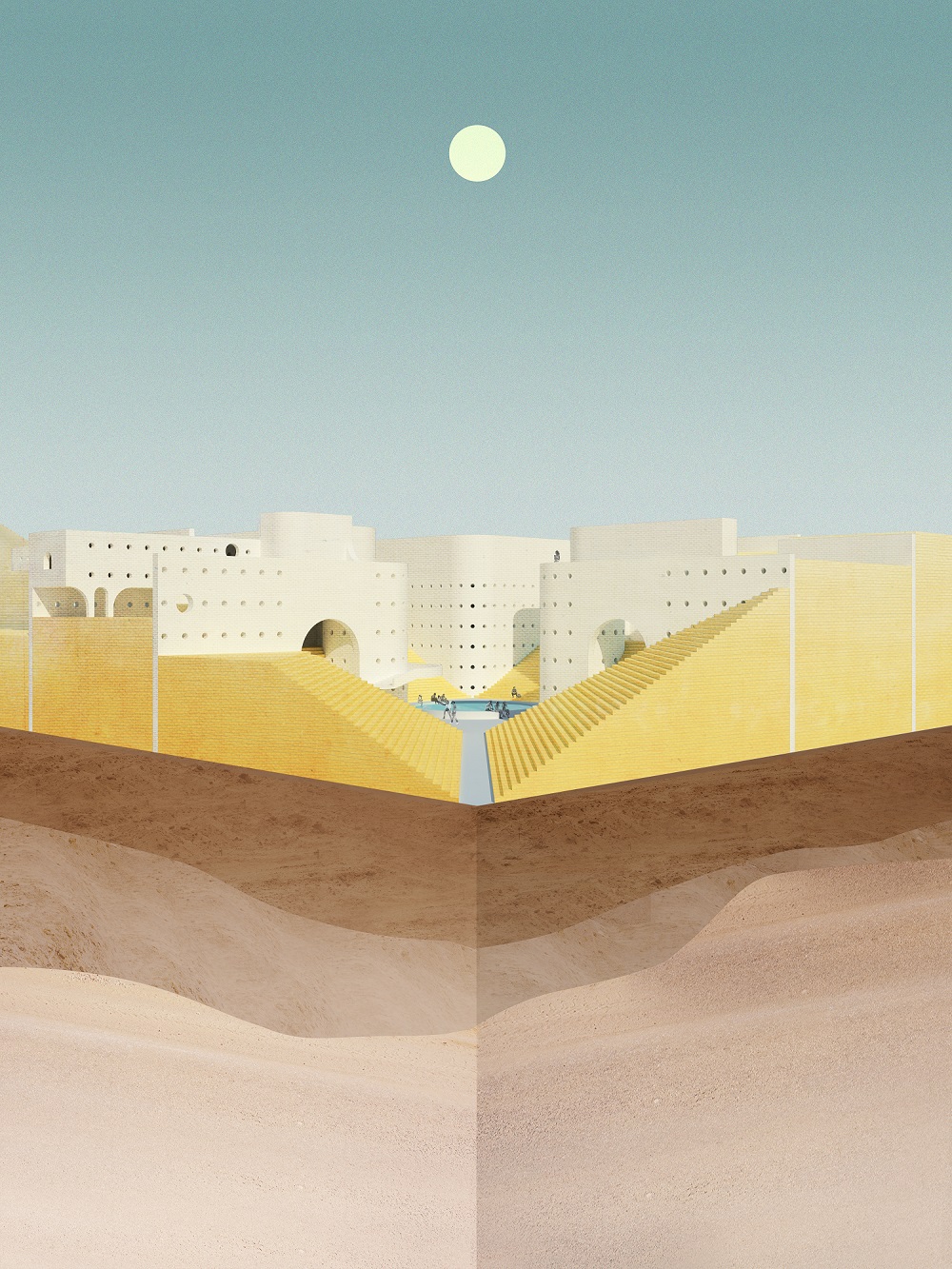

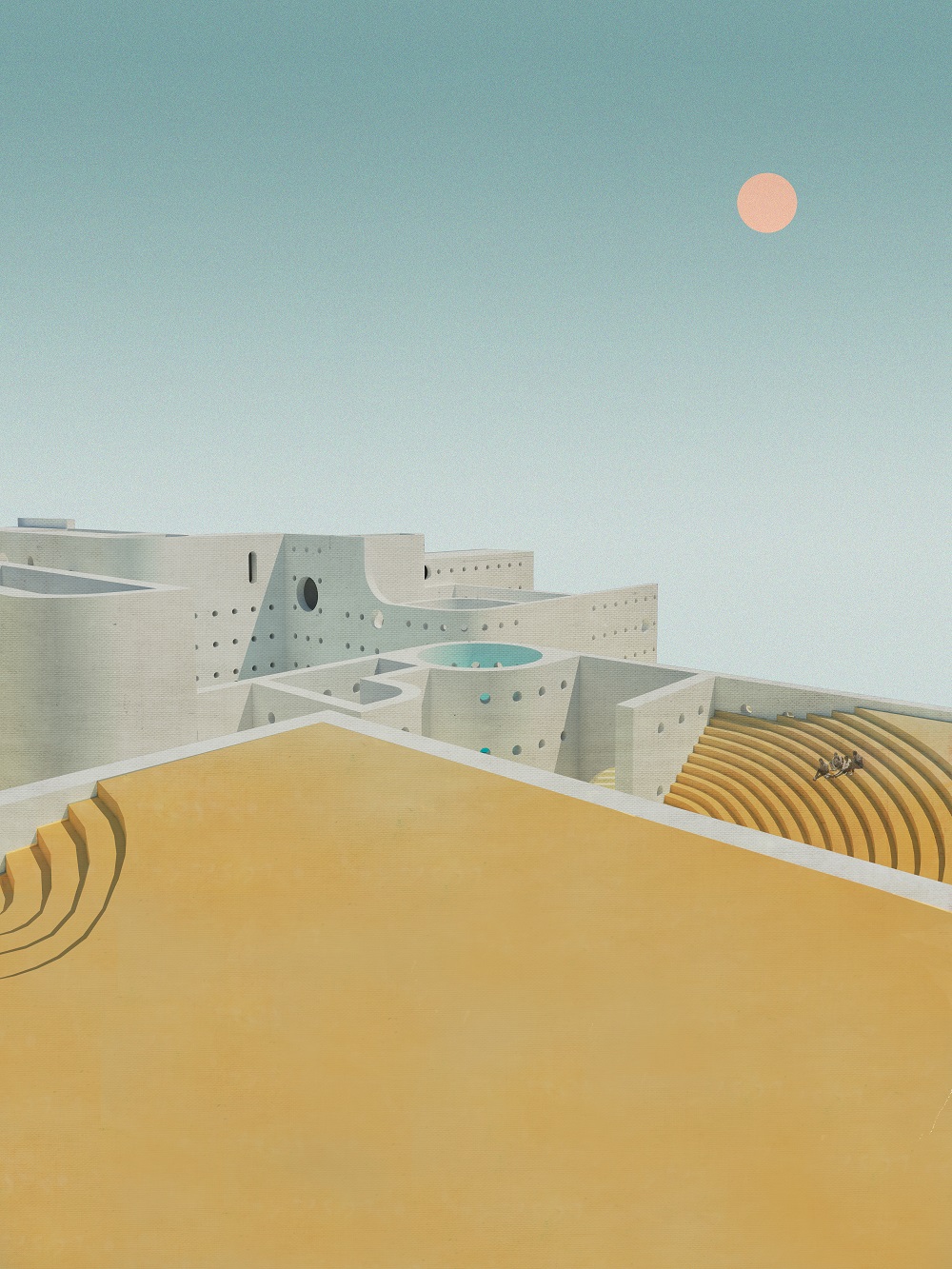

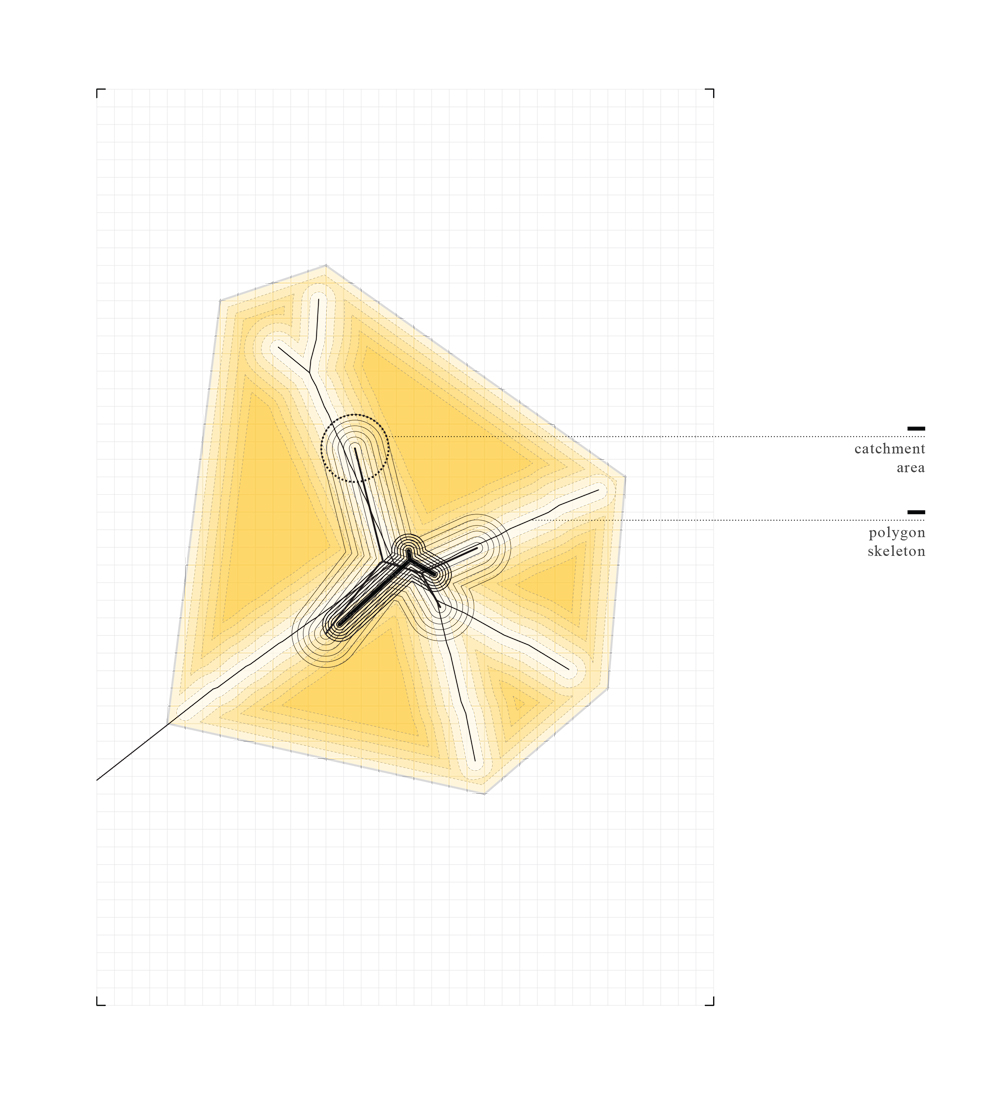

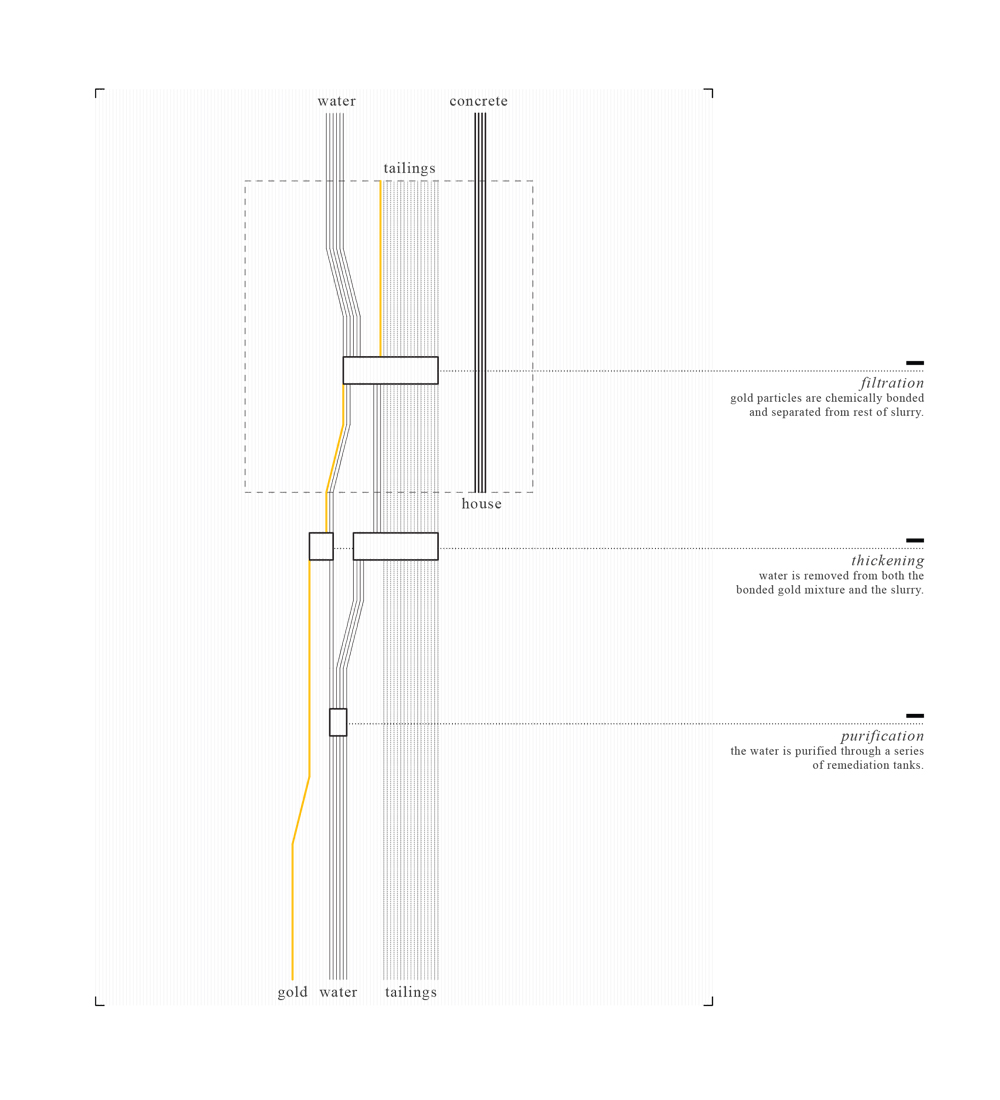

Birthed upon gold reefs, their mined detritus monumental within the urban fabric, Johannesburg is

perfectly situated to negotiate processes of extraction with those of construction as these artificial

mountains are now being hydrologically excavated for redevelopment. This project is a functional

choreography of the regimens found in everyday life with the infrastructure of resource production -

of water and gold - upon which these rituals are built, in an attempt to materialize through

architectural agency the conditions of extraction that are typically unseen.

: A landscape of performance.

| TYPE | studio |

|---|---|

| YEAR | 2016 |

| FOR | m.arch I |

| SITE | boston |

| TEAM | grace la (advis), james dallman (advis) |

1

TERRAFORM AND THEATER

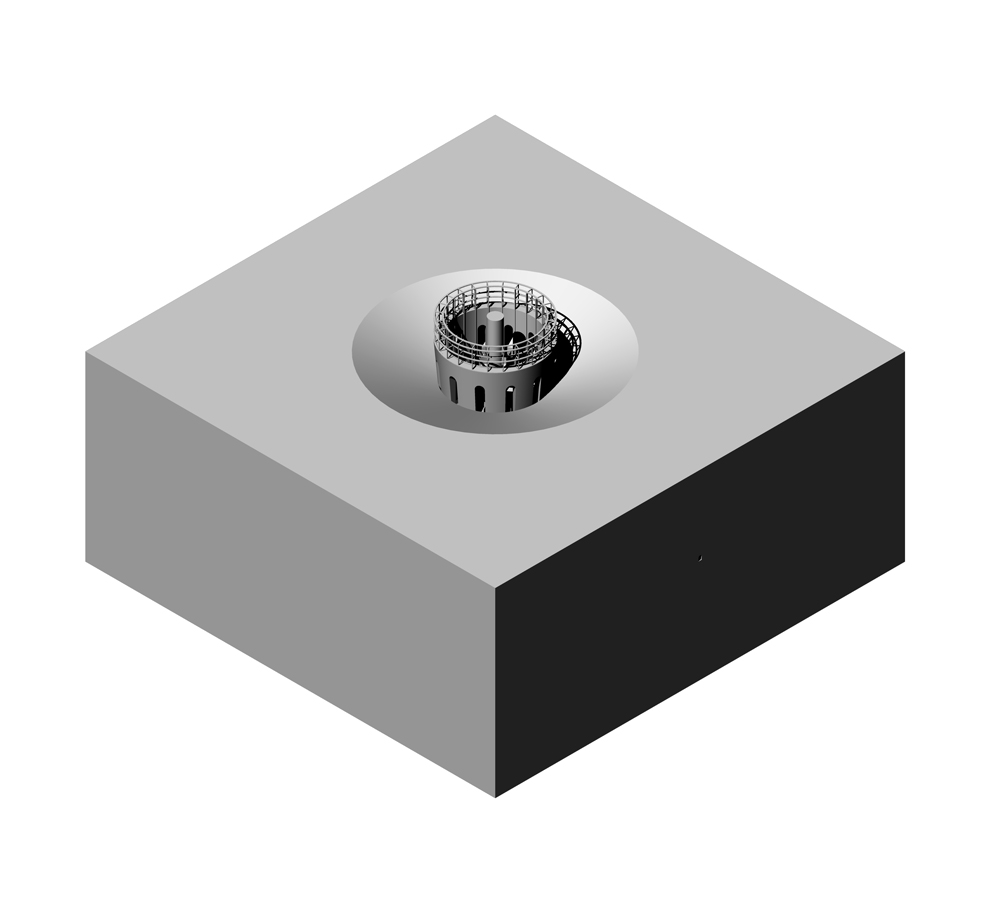

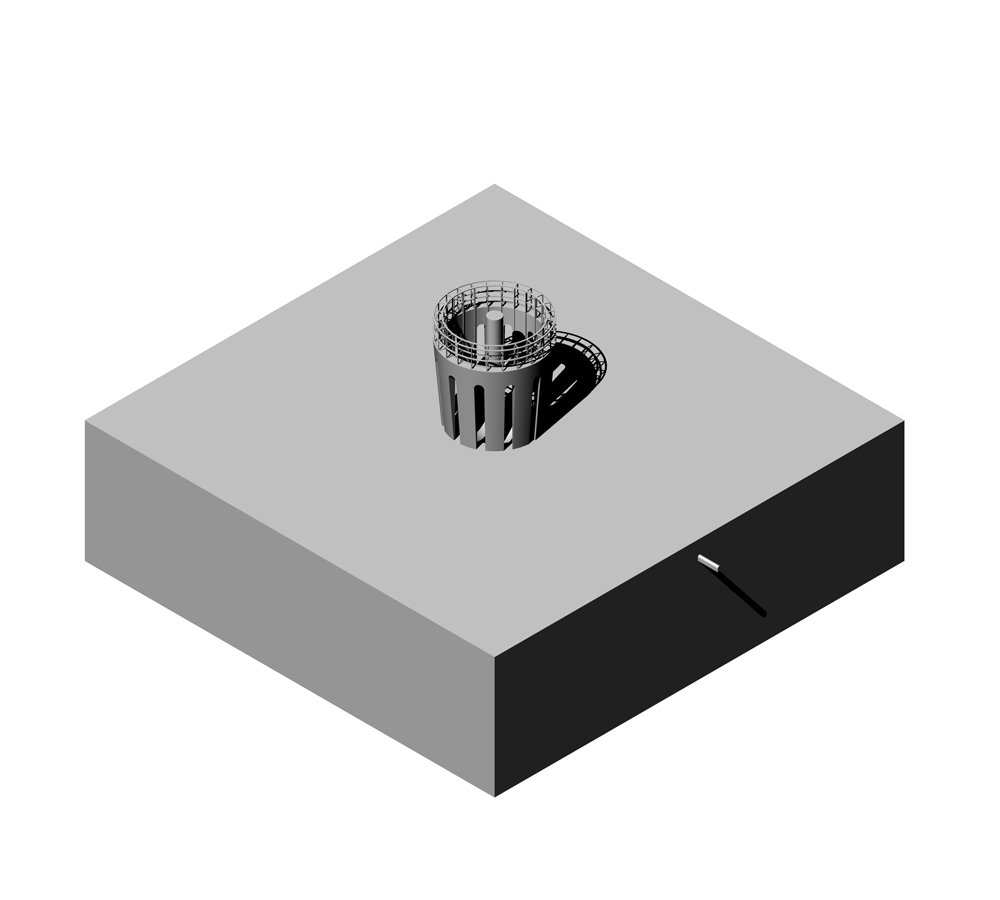

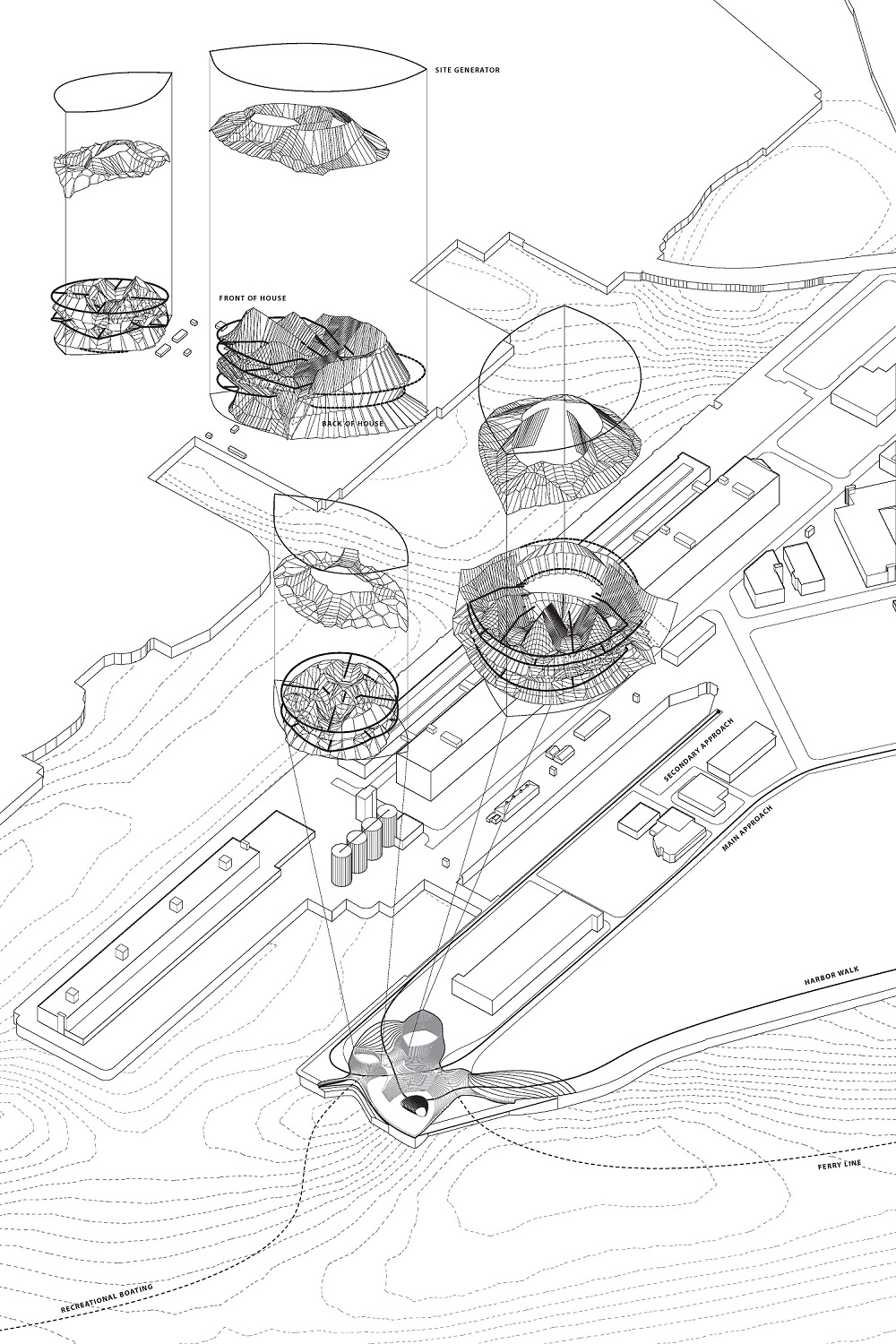

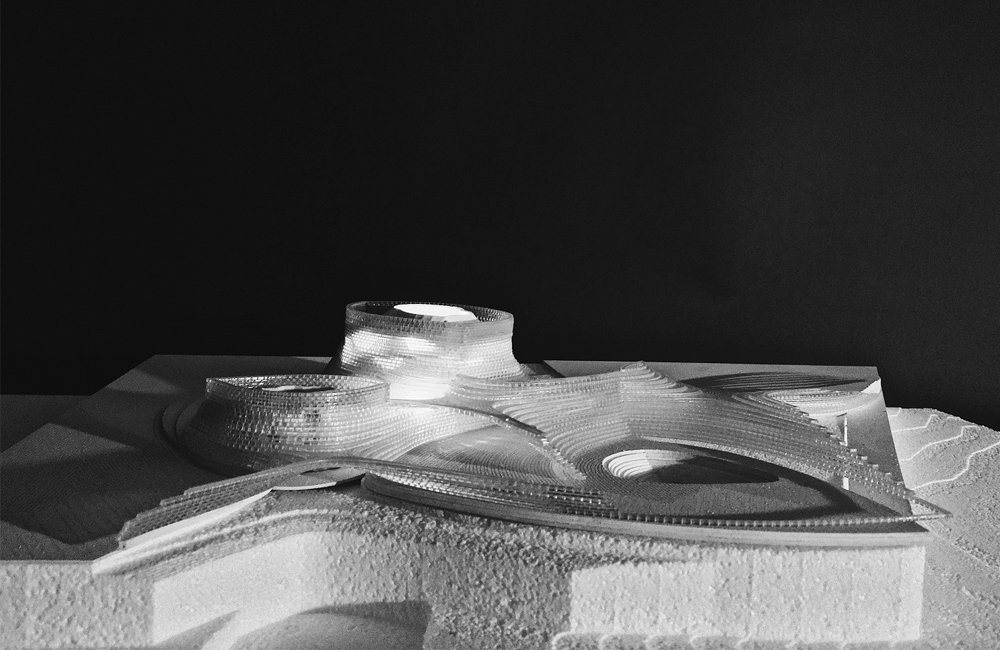

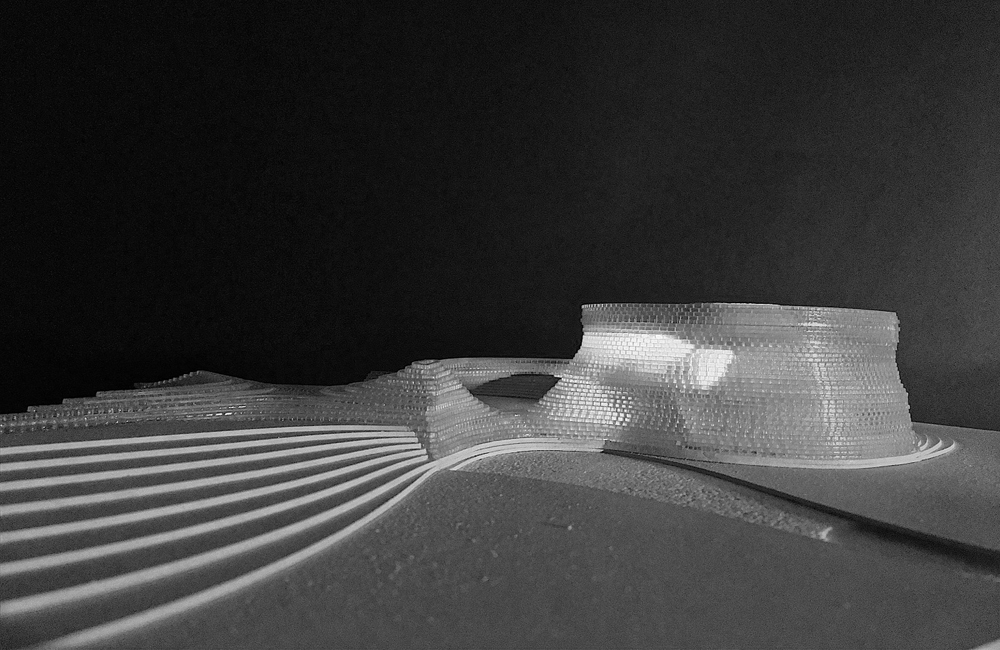

The question of a new civic surface for north Boston's developing seaport area targeted its

emerging identity as a post-industrial birthing grounds for cultural institutions in conjunction

with a high-tech maker scene. Our studio paired the programmatic brief of a performing arts center

with landscape manipulations to address the ebb and flow of access to our waterfront site: how

does approach by water or by land, by performers, patrons, and support staff, carve into our hard

industrial landscape and culminate into a single, contiguous event space?

Design considerations center around three primary elements: a bicameral theater with a major and

minor stage, and the formal landscape conditions leading up to and surrounding the performing arts

center.

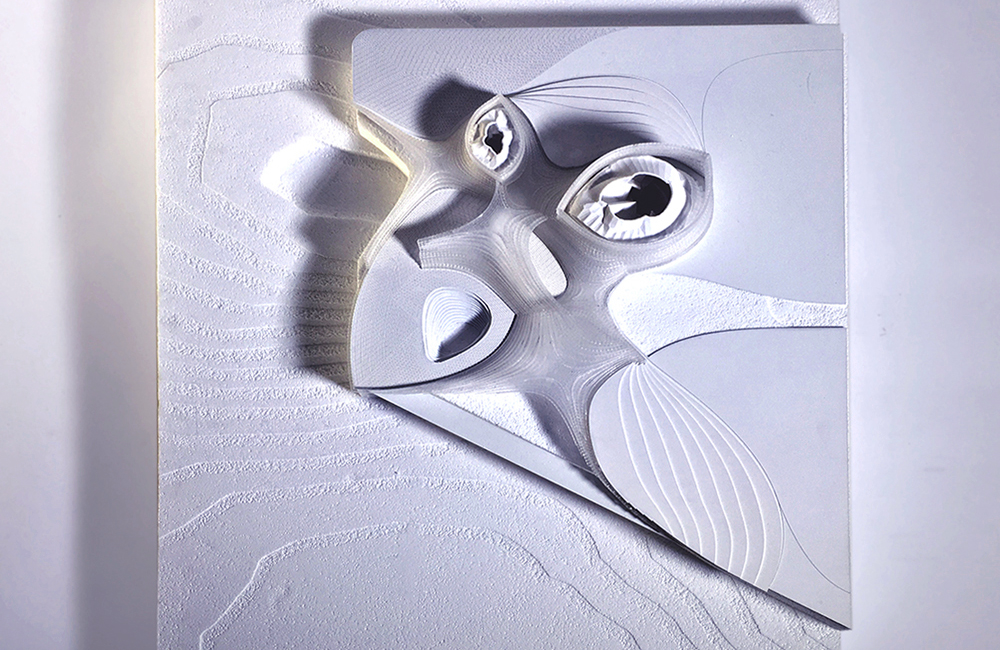

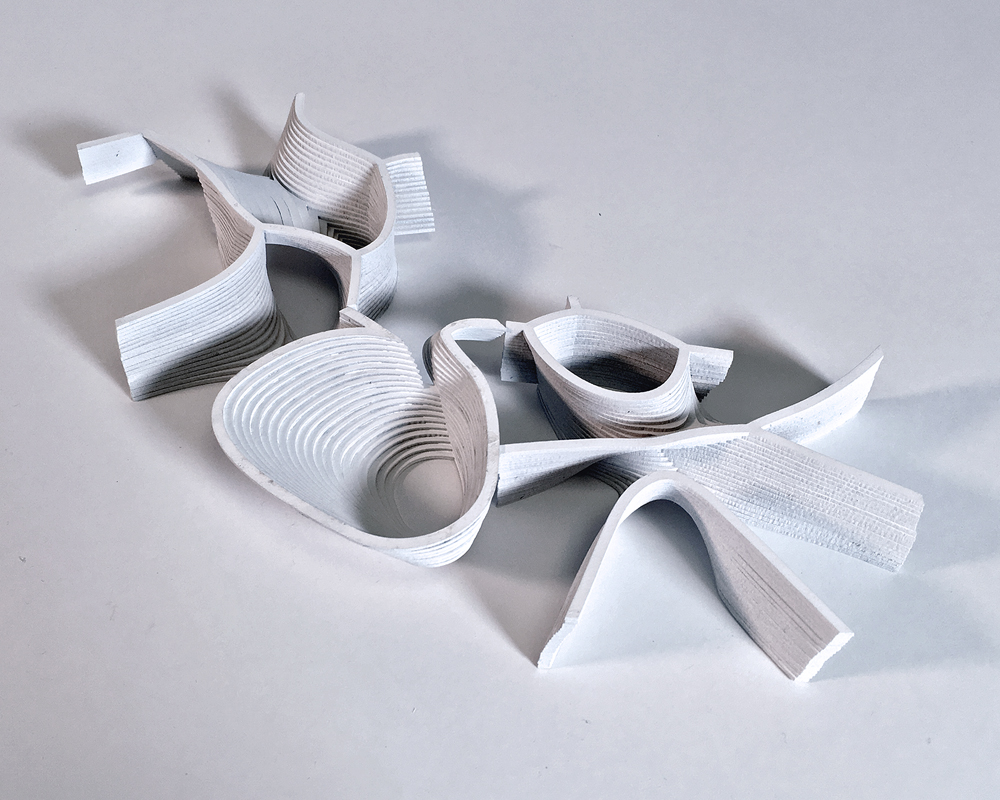

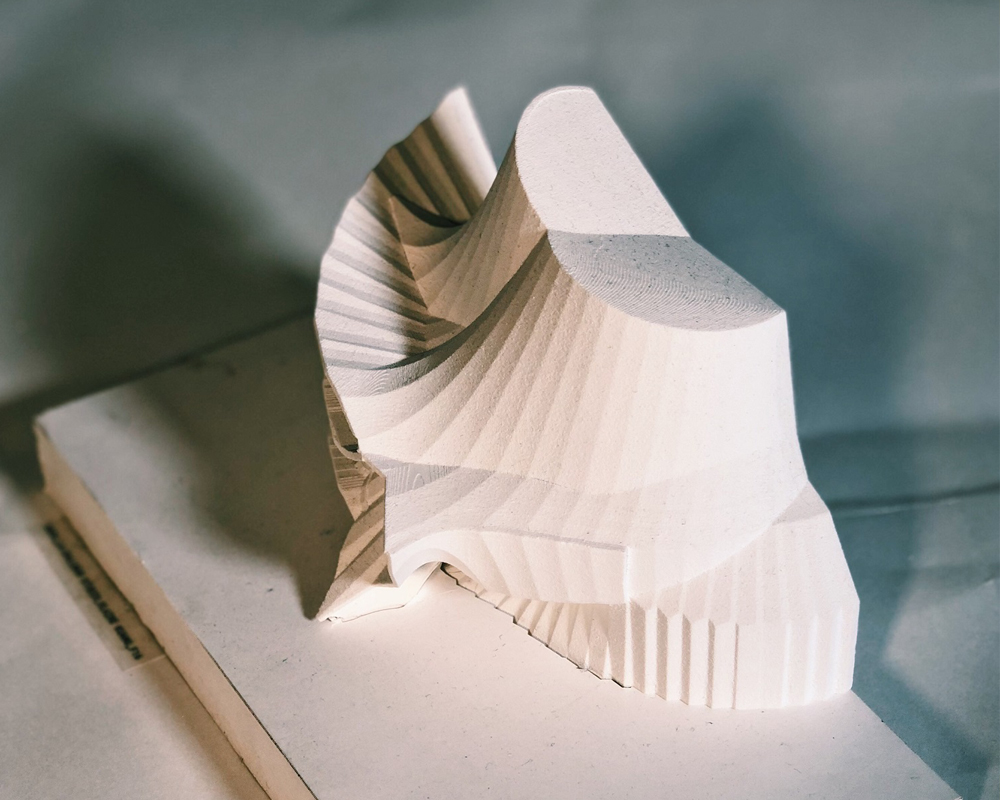

1.01Landscape studies

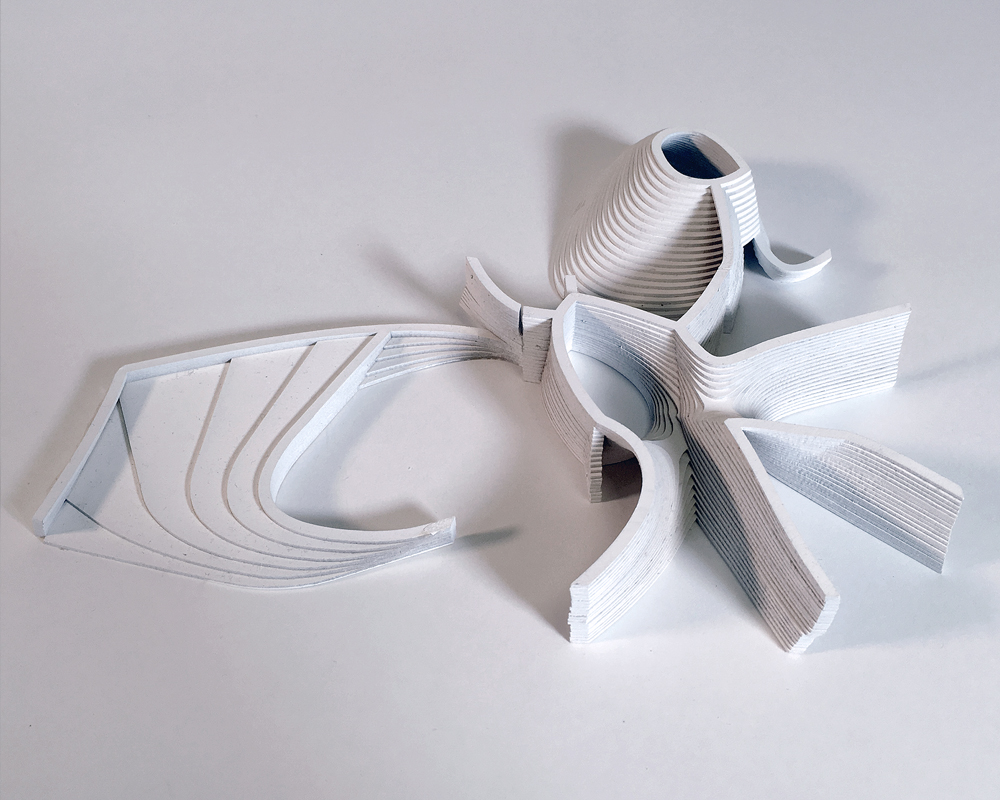

Our investigations began with a series of studies of natural geological formations as inspiration for our performance landscape. The honeycomb erosion patterns of sedimentary and plutonic stone seemed particularly apropos here, given the proximity of our industrial seaport site to the waterfront: these lacework patterns form a series of small, tightly adjoined cavernous connections that penetrate hard stone as a result of cyclical dry/wet applications of salt-rich water upon its surface.

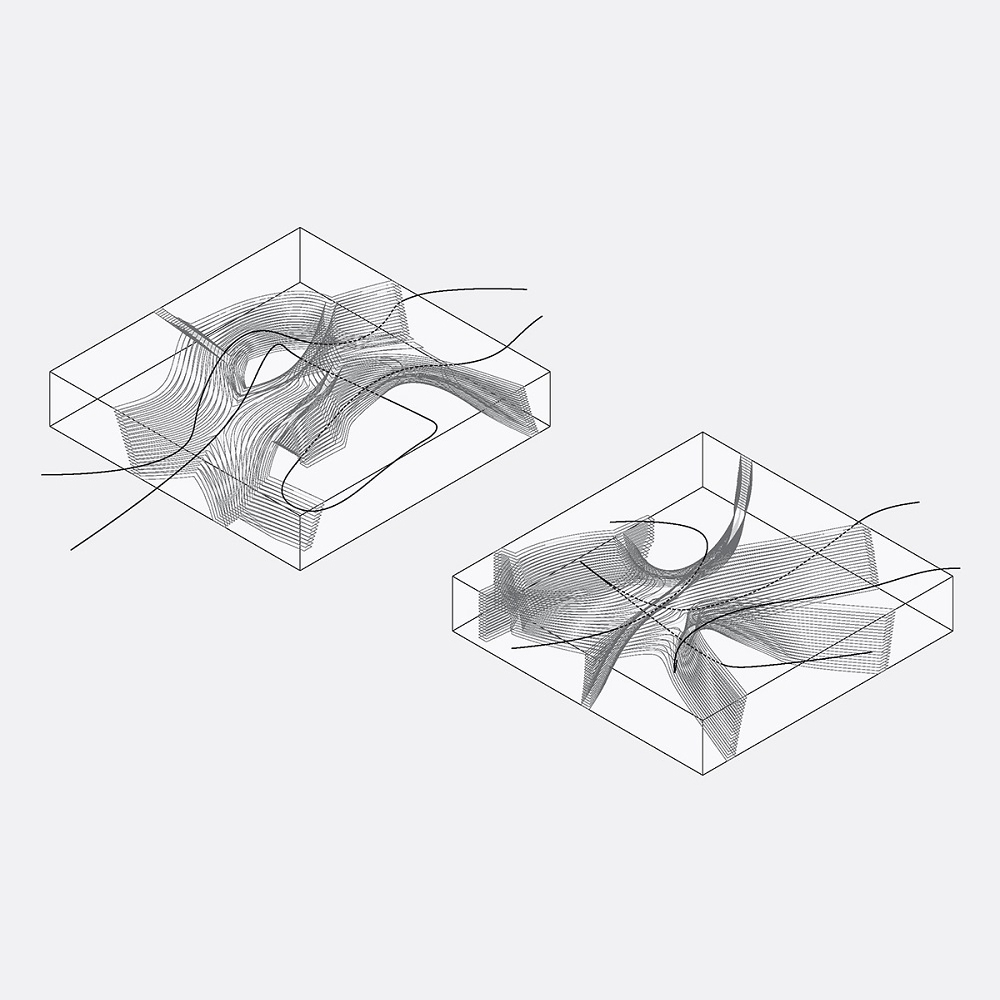

The process of reconstructing these surfaces into a layered, three dimensional topological model from 2D images posed a challenge of extrapolating the cavernous connections below the first layer of rock: this was eventually achieved with a script that generates spanning surfaces from driving curves which connect each of the surface level cavities.

Abstracting this technique - of using driving curves that represent the erosion path to generate the medial surfaces between and around them - yielded more figural blocks that could be more precisely controlled and rearranged to yield various permutations of connecting paths and surfaces. In part bespoke and in part computed, the curve generator method emerged from these landscape studies as the primary design driver for the relationship between circulation, form, and surface.

1.02Precedent studies

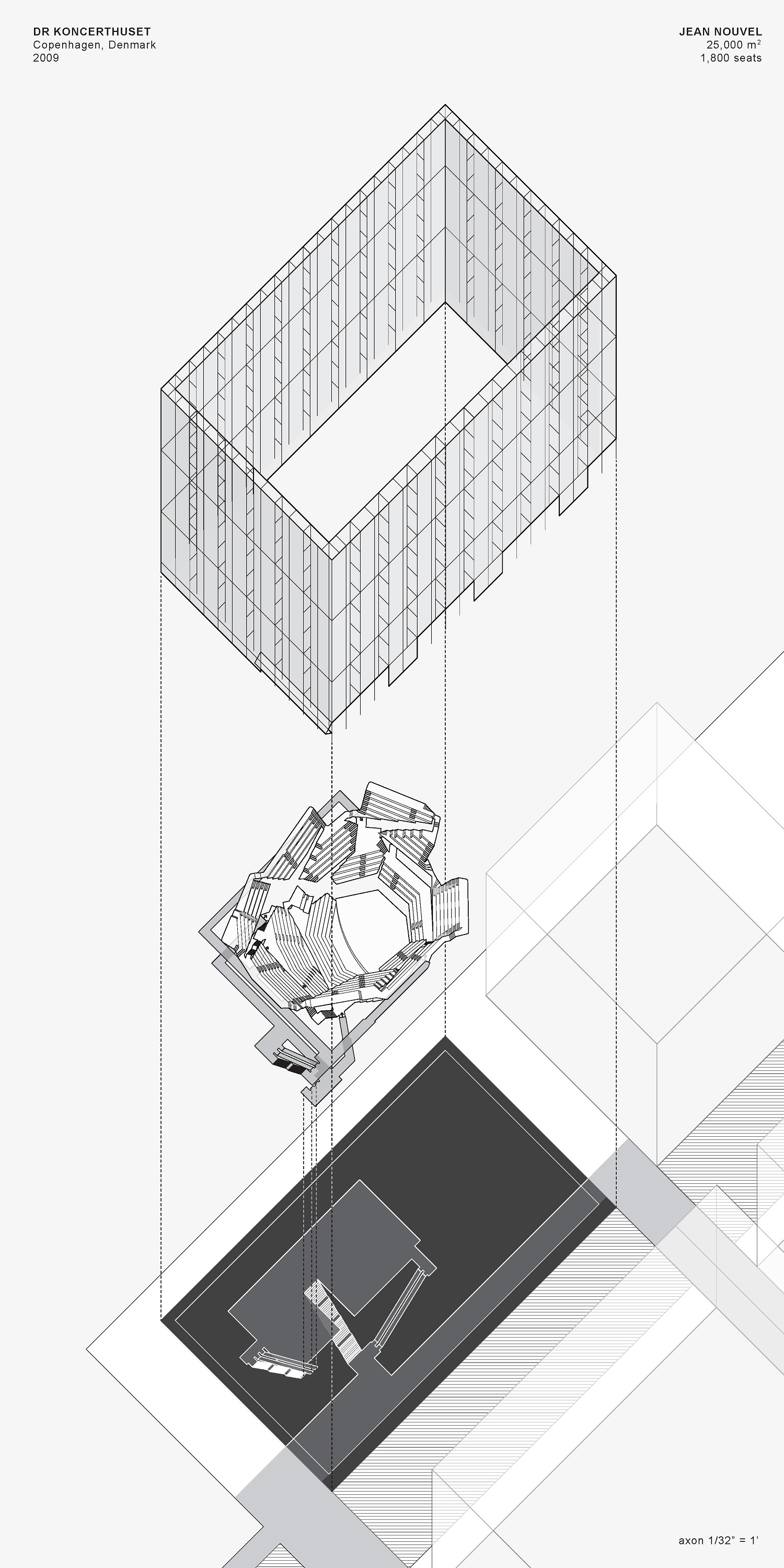

Our second assignment looked into performance space precedents as a means of familiarizing the studio with the complexities of theater design and exposing us to strategies of programmatic organization. A deconstruction of Jean Nouvel's DR Koncerthuset in Copenhagen provided a straightforward and didactic approach to performance space, distilling it into three conceptual parts: (1) envelope / enclosure, a simple box which for Nouvel also performs as a billboard on the urban scale, (2) concert hall, a voluptuously articulated hermetic object embedded at the core of the building, and (3) circulation, an interstitial series of floating platforms, stairs, and escalators which connect the building entrances to the concert hall points of access, at times programmatically bloated with back-of-house and administrative spaces.

2

CIVIC SURFACES

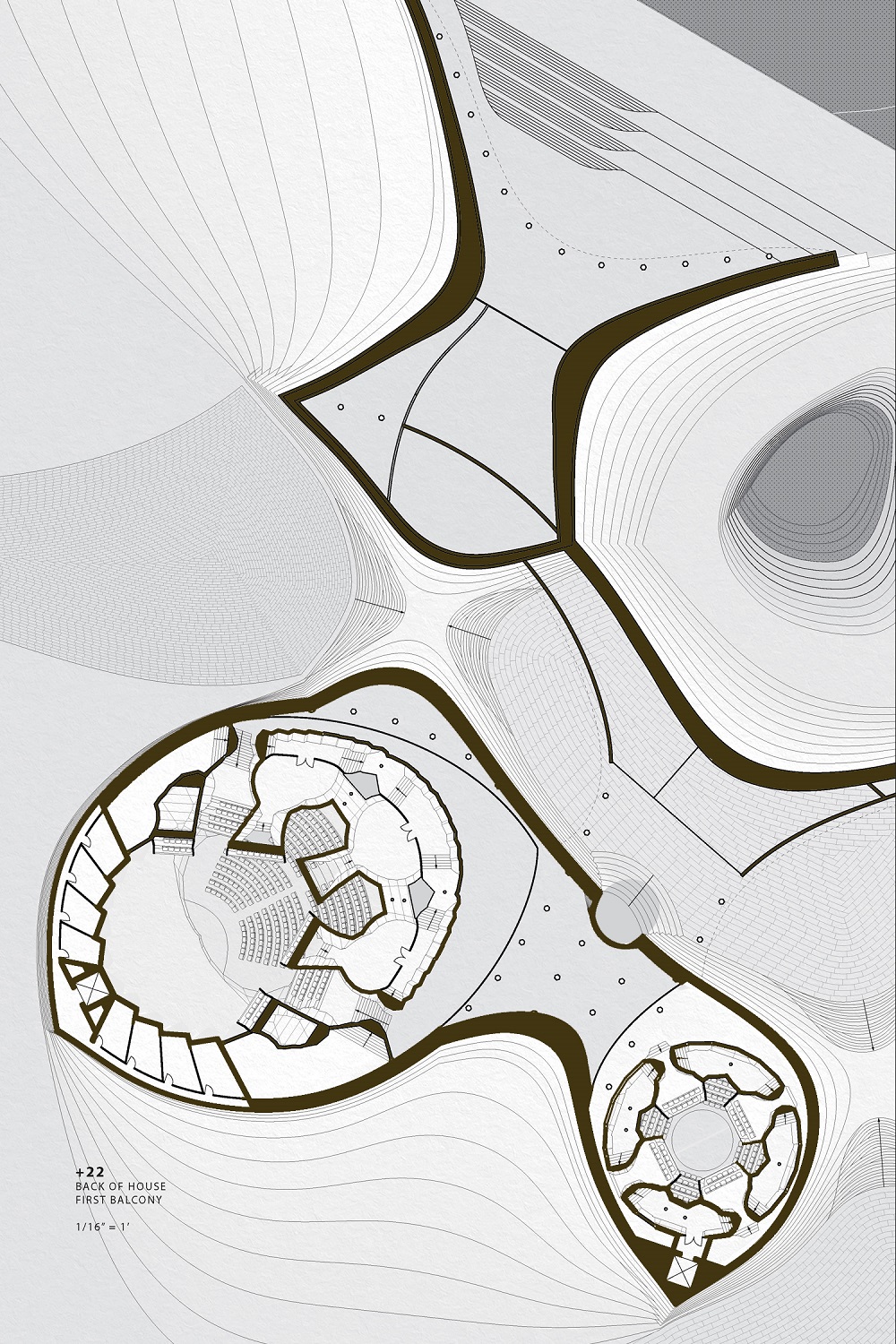

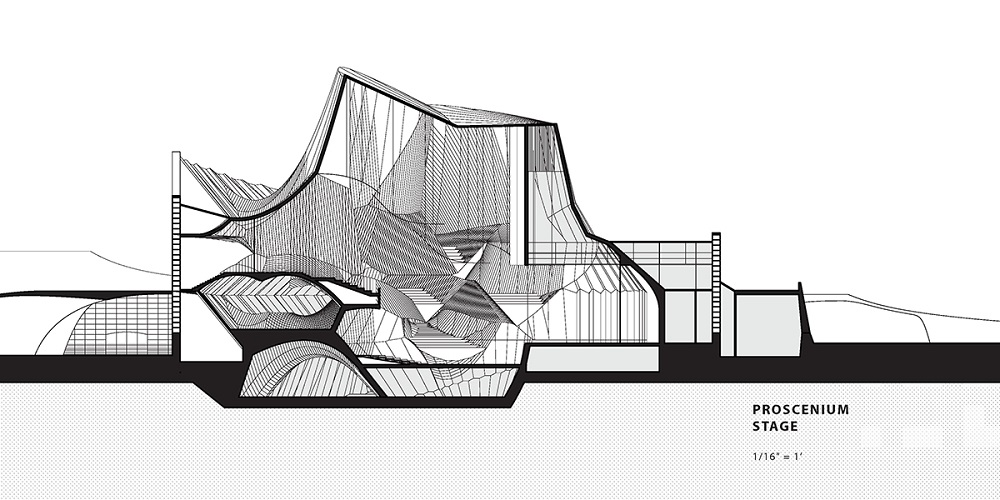

Where Nouvel kept his tripartite elements formally distinct, I propose a total, unapologetic fusion of envelope and theater into a contiguous surface, using the generative technique developed earlier. The site is terraformed by circulatory paths with two approaches by land, and one by water, giving the building its overall massing. Each theater is treated once again as a hermetic object: however, their generating curves are determined by line of sight from each balcony to the stage, in a proscenium formation for the large theater and in the round for the smaller theater. By using the same underlying mechanism to generate surfaces for both the envelope and performance spaces, the project coalesces into a singular, speculative expression of form and tectonic.

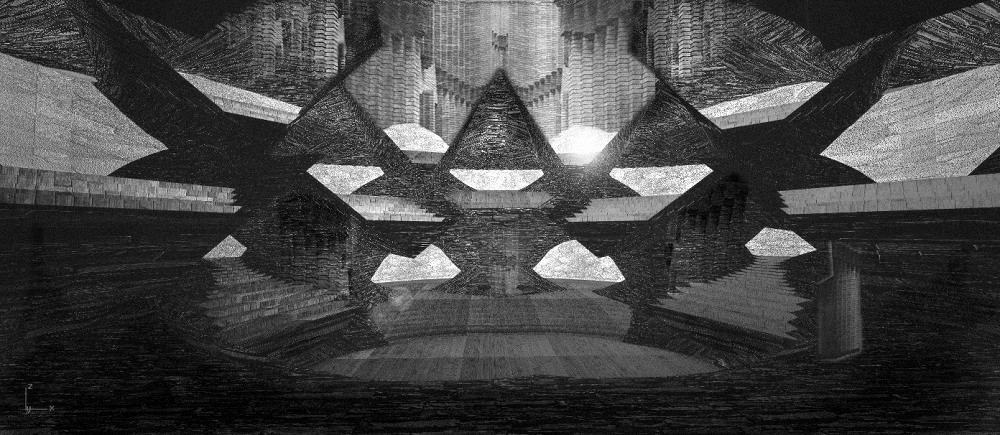

2.01Brick by brick

The generative nature of these surfaces necessarily exudes a sense of the foreign in how they partition space. The theater buildings affect the Promethean - something alien, something carved by inscrutable hands. In parallel reckoning, I chose a monolithic brick to both heighten the effect of monumentality and imbue the project with human scale: brick expressionism vis a vis extraterrestrial terraforming.

2.02Shaped by flow

Auditoria are traditionally blackboxed, where careful control of lighting and sound is quintessential for performance. Here, the auditoriums are strongly defined by balcony seating, rather than orchestra, to encourage interpersonal intimacy in a space where attention is directed almost entirely center stage. Each balcony is generated by a line of sight to the stage, but also extended outwards towards the building envelope, penetrating the mass of the building which allows for the theatricality of natural light and architecture to perform if doors are left open.

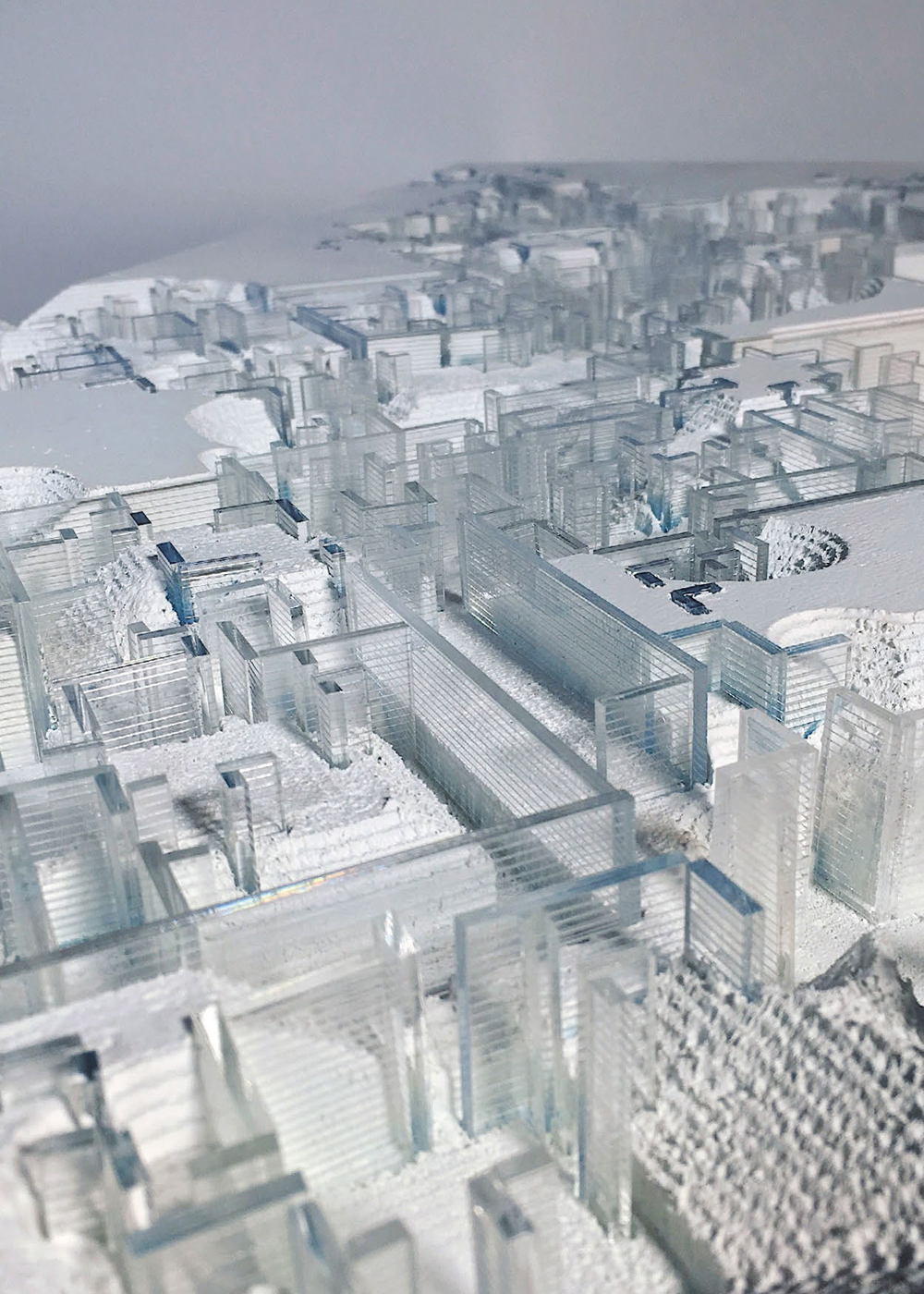

The site is similarly monolithic, but sculpted in a glass brick. During the daytime, the glass allows natural light into circulation and back of house program without breaking the effect of solid mass construction. At night, the effect is reversed: the translucent envelope exposes the form of the porous, illuminated auditoria to the rest of the city, by land and by water.

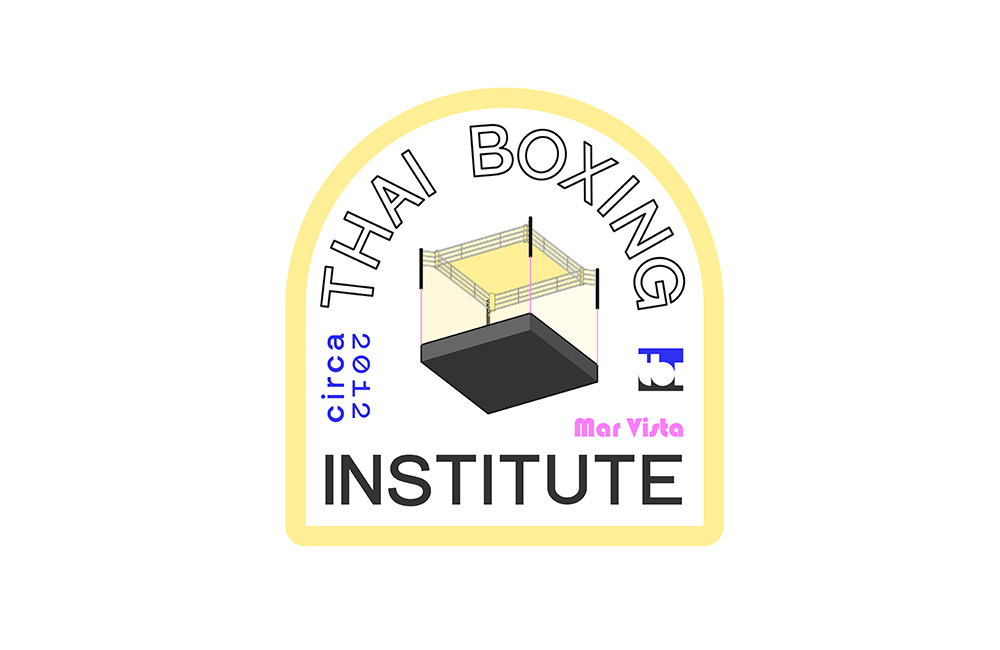

GRAPHIC

: Identity for a muay thai gym.

| TYPE | branding |

|---|---|

| YEAR | 2019 |

| FOR | thai boxing institute |

| SITE | los angeles |

1.01A conversation with coach Vic

When Vic Acosta started his own Muay Thai gym 8 years ago, he had no idea what he was doing. He came

from one of those old Angeleño communities, where everyone spoke spanish and moved with slow honeyed

limbs - the kind of Van Nuys suburbia where you didn't start your own business, and you didn't know

anyone who did, either. In the years that followed, full of the

use-it-till-it-breaks-and-then-use-it-for-a-bit-longer, learn-on-your-feet-and-figure-it-out,

watch-your-gym-burn-down-and-start-over-again kind of stories, coach Vic managed to patch together what

is now a thriving cross section of community that is starting to outgrow the small 1400sqft gym nestled

in the corner of Venice and MacLaughlin.

A couple of months into my membership, I sat down with Vic at a nearby coffee shop to talk brand. It was

an opportunity to engage in a more personal kind of design, to try and articulate what it was about this

local gym, its windows always fogged over with exertion and ringing with the staccato sounds of pads

depleting, that so effectively drew me in to a sport - intimidating to the uninitiated - that has since

become both routine and ritual.

1.02Artistic aspirations

On the side, Vic also fronts a small 3-piece rock band with two other members from the gym. Having grown up firmly under the influence of sounds from The Arctic Monkeys, Elliott Smith, and Circa Survive, Vic taps into the punk rock mentality of anti-establishment resourcefulness: an attitude reflected in the gym's graphic presentation. Avoiding the typical symbols of boxing and competitive gyms, with their violent reds and victory blues, with kicking silhouettes and swinging gloves, he pulls up Takasan's curated instagram account of old school muay thai posters for inspiration. We glimpse 3D pink word-art headlines over a faded fighter clad in puffy periwinkle shorts, yellow ochre gradients and kitschy perspective distorted backdrops, and a poorly cut-out silhouette that is both compositionally patchwork and endearingly earnest. "I've been really into pastels", he notes, "but more professional".

1.03The Ring and the Wrap

Vic's attitude towards muay thai as a martial art encapsulates his approach to teaching: he emphasizes technique over power, grace over aggression, and impresses deeply the foundational impact of always being aware of oneself and one's orientation relative to others. This presence of mind and economy of movement translates into concise, strategically contextual, and clear demonstrations. Carefully observing each student's stance, he makes small adjustments for radically more impactful strikes, and creates thoughtful combinations where the chaining of weight shifts leaves no breath wasted and no trajectory without purpose.

To symbolize these qualities of precision, technique, and rhythm, I chose not the boxing glove, but the handwrap as the design basis for TBI's main logo. The wrap functions as the substructure that gives articulation to the hand when clenched, keeping fingers distinct and separated upon impact, joining the hand and the wrist as a single vector extending from turned ankle to engaged core before terminating in the arm outstretched. Above all, it is in the small, studied moments of preparation, the unrolling of wraps and idiosyncratic, repeated layering of fabric over and around and between the contours of the hand, that one finds ritual in the practice of martial arts.

The construction of the wrap logo focuses on clean curves and hard lines to convey the dualities in Vic's gym motto, "the art of striking and the science of fitness". Each letter connects with the next to convey flow without losing the technicality of intermediary lines decorating the handwrap fabric. Muted solids and a varied color scheme captures the charm of eclecticism while remaining grounded and professional, while conversion to a high contrast black and white emphasizes the form of the logo in a more universal representation of the Thai Boxing Institute.

: Exercises in Drawing.

| TYPE | multimedia |

|---|---|

| YEAR | 2018 |

| FOR | various clients |

| SITE | none |

| TEAM | none |

1

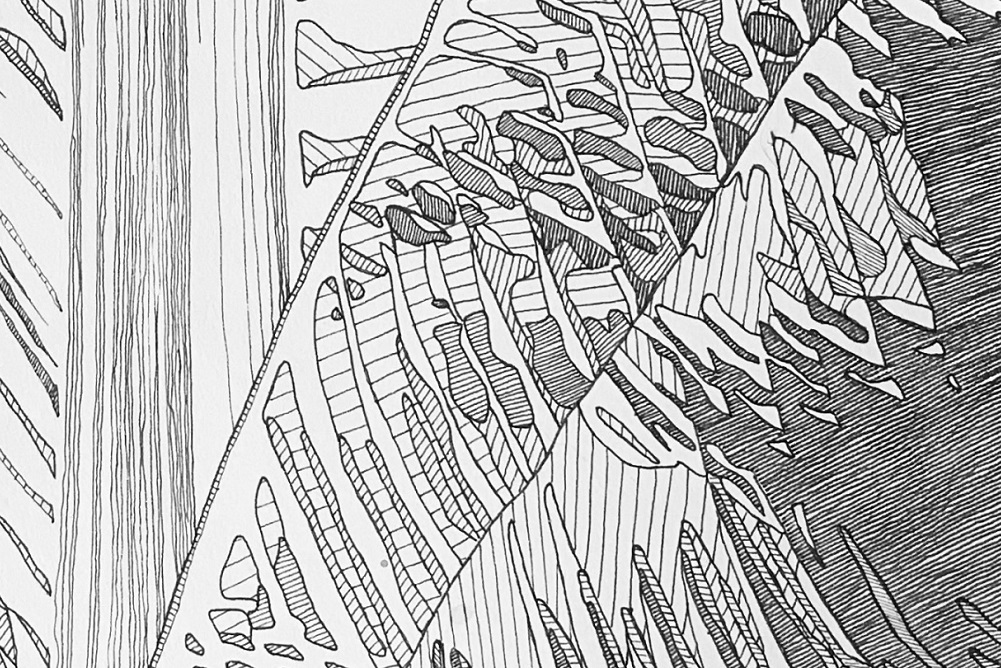

BRAMBLE, 2018.

A wedding gift for two dear friends who bonded over their shared passion for poetry, Bramble was inspired by a favorite piece by Robert Hass.

2

MUSA, 2020.

A gift for a ceramics friend who experiments with many glazes, Musa abstracts the banana leaf into a composition of textures.

PROSE

: Andrea Palladio in Los Angeles.

| TYPE | essay |

|---|---|

| YEAR | 2019 |

| FOR | pax monographs |

| SITE | los angeles |

“Tip the world on its side, and everything loose will land in Los Angeles.” (1)

The narrative of 20th century Los Angeles begins with the formulation of a human ecology. As first

generation immigrant colonies gestated within major metropolitan areas in the United States,

sociologists predicted a race relation lifecycle of contact, competition, conflict, and ultimately

a spatial assimilation as American suburbia slowly absorbed these foreign bodies. The stage was set

for instability. Underneath the negotiations of territory and belonging in the decades that followed

lay a theater of cultural identity and cultural (re)production, enacted by displaced individuals and

communities asking the same, persistent question: “we are not from here - so who are we?”. Palladian

ideology, deeply rooted in the turbulent geopolitics of its own period, provides a particularly timely

framework through which Los Angeles may remediate its contextual amnesia and establish a sense of

place.

Los Angeles has never professed a singular spatial syntax, nor a coherent architectural grammar; it is

a city assimilating in perpetuity, of make-believe homes owned by imposter inhabitants. Local

structures, infrastructures, and superstructures are constantly redefined during acts of identity

protest: the provisional non-Japanese repopulation of a vacant Little Tokyo during internment

following the attack on Pearl Harbor in the 1940s; the blockbusting origins of black Compton born from

fear-driven white flight in the 1960s, at a time where ninety-five percent of Los Angeles had racially

restrictive covenants against minority residents; the violence of the Rodney King riots rendering

visible the informal boundaries of a vigilante Koreatown in the 1990s, self-patrolled with

semi-automatics along storefronts and rooftops that made explicit the racial lines of a vandalized

minority community (2). These iridescent upheavals leave behind houses, shopping centers, roads, town

halls and churches like a shed husk, awkwardly fit to their incoming residents: insecure in their own

heritage, they are fertile grounds for the reinvention of the commons, a migrant Order in a

palimpsestic, self-masticating city where entire neighborhoods are digested, rewritten, and reborn in

situ.

These moments of identity crisis and identity formation are captured in the small dramas of

neighborhoods forced to become something culturally other. Take Olvera Street in downtown LA, 1930: home

to a century-old Mexican community - poor, disadvantaged, rundown - and the perfect crucible for

southern socialite Christine Sterling to test the commercial and touristic potency of a recently

imported, romanticized Spanish Colonial Revival style. In a singular move that Ada Louise Huxtable would

later describe as “the glorification of the unreal over the real” (3), a curiously American phenomenon

driven by consumer obsession with iconic re-creations that appear more real than the original, Olvera

rematerialized overnight not as authentically Mexican, but rather as a sort of Mexican kitsch, a shallow

copy of terracotta tiles and stucco arches now considered to be Californian vernacular.

This was the architectural context in which Frederic Hsieh, a young and hotheaded Taiwanese American

realtor, found himself dismissed by a distinctly affluent housing board, which accused him of “trying to

come into their living room and changing the furniture” in his bid to convert the sparsely populated but

predominantly white Monterey Park into a Chinese Beverly Hills. As an alternative to the low-income,

densely populated urban Chinatown (4), Hsieh dreamed of both resort and refuge for the Chinese during the

1970s, a time when East Asia was disintegrating, immigration quotas were expanding, and globalized trade

took center stage on the national political agenda. As a result of his efforts, Monterey Park and the

nearby San Gabriel Valley have since rapidly transformed into a constellation of decentralized

ethnoburbs, immigrant growth machines that are spatially entangled and yet operationally liberated from

their old suburban hosts. Within this re-colonization resides a consumptive inheritance of Spanish

Colonial structures erected by wealthy white Protestants, now garnished and ornamented with sometimes

exclusively mandarin signage.

Palladio was no foreigner to socioeconomic conflict. In the sixteenth century, the Ottoman Empire’s

seizure of former Venetian colonies induced widespread food shortages and famines which prompted

Venice’s merchant elite to consolidate formerly communal agrarian territory in Veneto and Verona.

Tensions between the wealthy landowners and the disenfranchised peasants, who worked these now privately

owned lands, were subsumed within the authoritative, hierarchical, and distinctly Italian language of

the classically-trained architect: social instability was masked by idealized form, mathematically

proportioned and symmetrically aligned (5). Thus, the Palladian Villa is always, at its behavioral and

functional core, a negotiation between domesticity, public cultural identity, and agricultural

production. The archetypical villa masses the private residential quarters at the focal point, insulated

from the convulsing landscape by an exterior ring of subsidiary programs such as barns, stables, and

service quarters—a spatial arrangement which suggests both dominion of and defense against a rapidly

changing geopolitics. In the absence of grand civic buildings, Palladio’s villa serves as a domestic

collective space for the gentrifying rural Veneto, a cross-section of servants, patricians, and their

various guests, tied to their surroundings by their origin as working farms.

The Veronese outlier Villa Serego is singular among the proposals of the Quattro Libri: instead of a

domineering primary residential volume distended by smaller secondary and tertiary structures, the

Serego instead captures, at its core, a void. Contained within is a courtyard, echoing the communal

atria of ancient Roman dwellings, and a double portico as a vestibule to both the adjacent private

quarters and a public-facing peristylium. This external courtyard is sliced open, flanked by two

agricultural areas, and unconventionally lined with a heavily-rusticated Ionic colonnade which

references the stylistic qualities of earlier Veronese buildings. Here, the colonnade is our primary

actor: it is the organizational interface between public and private, always present and negotiating

between an intimate collective, the domicile, industry, and the open landscape. The mercurial quality

of Villa Serego is further illustrated by its built history and bastardization of Palladio’s original

design, spanning four centuries of broken construction. Serego is a synthetic narrative of partial

ownerships and grafted styles, functioning intermittently as residence, farm, and winery, and

persistently, through its open courtyards and colonnades, as a semi-public commons.

Much like the fragmented Venetian colonies before Palladio, the disparate ethnoburbs of Los Angeles

lack a symbolic and visual language of a Commons around which these volatile communities can articulate

their cultural but contextually agnostic identities. For an ethnically regurgitating Angelino suburbia,

the Palladian equivalent of Villa Serego must by necessity negotiate unreal heritages using ornament and

the colonnade as a mediator between old and new, and graft the pastoral, bucolic Arkadía of Veneto onto

the modern day, bulimic Arcadia of the San Gabriel Valley. In the now predominantly Chinese and Latino

ethnoburbs of East Los Angeles, these public spaces are no longer the traditional loci of authority -

churches, government buildings, transit hubs and parks - but rather shift into the most productive

bastions of cultural identity: commerce and cuisine. The suburban villa emerges de facto as the

quintessential corner shopping plaza, with family-owned restaurants and grocery stores sitting piecemeal

like recalcitrant line cooks in a parking lot, where residents rich and poor, from neighboring streets,

neighboring towns, from across a hard, brutal Los Angeles, congregate underneath shaded overhangs and

take seat around home-style dishes from some foreign, yet uncannily familiar land.

Instead of the cultural ecdysis that often accompanies radical shifts in development, the new commons

would resonate with an ever-changing residential population by layering migrant typologies upon existing

styles, and over time developing the patina of idiosyncratic assimilation. The diminutive Las Tunas Plaza

in San Gabriel, with its asphalt courtyard and row shops just slightly askew, is a perfect case study and

site of proposal for this architecture of accumulation. A simple addition of distended porticos, dressed

in Chinatown generic and emblazoned with neon hanzi, carefully sutures the language of its new

inhabitants onto buildings still clad with stucco arches and spanish tile. Each column mirrors the

haphazard partitioning of its ersatz colonial host, establishing a negotiated grid that gives structure

to these poorly tailored hand-me-down spaces, irregularly placed but now aligned to the urban fabric.

Double colonnades expose the dual nature of consumption: a caustic city on one side and quiet residences

on the other, while providing pedestrians the civic space that suburban communities desperately need. The

roadside shopping plaza, restructured with public porticos, is ripe for a new migrant order; unassuming

and plentiful, they are humble portals between domicile and globalized commerce, garnishing the

intersections of major throughways and main streets, and stabilizing sites of conflict with the

architectural ethos and prosthetic vernacular of an itinerant Los Angeles.

_____________________________________

(1) Frank Lloyd Wright, on the creative looseness and cross pollination of styles within Southern

California. Perhaps also apropos to the ethnic origins of the city, traced back to 1781: of the 44 original

Pobladores selected by governor Felip De Neve, 26 were of African descent, 7 were Yang-Na Indians, and 9 of

mixed Spanish ancestry. Currently, of the major metropolitan cities worldwide, LA has the second largest

percentage of (documented) foreign-born residents (37.3%), with a non-white population of 48.6% (2018 US

Census).

(2) By 1910, Los Angeles had already primed the majority of its real estate with racially-restrictive

covenants. Curiously, mansionization of single family homes developed in response to this induced housing

shortage, such that prices could be increased vis a vis increasing square footage. Architectural critic Ada

Louis Huxtable describes these McMansions as “a grotesque aggregate of Rapunzel towers, pretend Palladian,

Jacuzzis and surround-sound”.

(3) The Unreal America: Architecture and Illusion, The New Press: 1991. Huxtable declares architecture to

be relentlessly self-referential, where cumulative heritage underlies even the most radical breaks from

style. She lambasts the term “authentic reproduction” as deceptively ahistorical, and differentiates the

real fakes from the fake fakes, selecting LA’s own Frank Gehry as a beacon of stylistic authenticity:

coincidentally, even he succumbed to Disney CEO Michael Eisner’s architectural imagineering and designed a

themed minimall on which he later commented, regretfully, “I lost control.”

(4) The newly minted Chinatown was a product of Hollywood set designers, and professed the stylistically

flat, one dimensional mise-en-scène of eastern exoticism intentionally commodified as an ethnic signifier:

this was an effort by the recovering Chinese community to rebrand themselves as a culturally coherent and

digestible destination.

(5) Mimar Sinan (1490 - 1588), royal architect to the Ottoman Empire, was familiar with the Renaissance

ideas of Alberti and also strove for ideal forms through geometric perfection. He shared a contact with

Palladio via his patron Marcantonio Barbaro, a Venetian senator who served as bailo of Constantinople for

six years: their mutual influences can be seen in the elevations of Sinan’s mosques post publication of

the Quattro Libri and in the spires of Palladio’s Chiesa del Redentore.

Two parts creative and one part technical, trained in math, design, and architecture. Currently a software dev at SPECKLE. Browse some neat places and spaces I've been on INSTAGRAM, verify my existence on FACEBOOK, peek my curriculum vitae on LINKEDIN, and see how I built this thing on GITHUB. Or, drop a line and just say hi 🙂